1. Green Building Lecture Series

Green Building series kicks off with “The Circular Economy: Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, Reconsider and Re-imagine”

Date: Thursday, Oct. 4

Time: 7 – 8:30 p.m.

Location: Scottsdale Granite Reef Senior Center, 1700 N. Granite Reef Road (northwest corner of McDowell and Granite Reef, behind the convenience store) There is wisdom in the old saying “one man’s trash is another man’s treasure.” What if instead of burying our trash in a landfill, we recirculated it back into the economy? What if we began to regard “waste” as a “resource?”

Scottsdale’s Green Building Lecture Series kicks off its new season with a discussion on the reuse and recovery of materials and products we use every day.

In a traditional linear economy, products are made, used and disposed of in the landfill. In a circular economy, resources are kept in use for as long as possible to extract maximum value, then recovered to regenerate new materials. Circular economies divert waste from landfills, reduce environmental impacts, conserve energy and water, save money and create jobs.

Speakers:

John Trujillo, principal of Circonomy Solutions, will lead the discussion. As former city of Phoenix Public Works director, he reinvented the city’s waste collection and recycling programs to dramatically move the city toward zero-waste. John will share business and public sector efforts to recover material resources for reuse and regeneration in an economically viable and environmentally compatible way.

2. Upper Gila Watershed Forum – How Do We Adapt to a Hotter and Drier Future?

September 28, 2018

Speakers: Randa Owens McKinney, Owens Properties, Sam Daley, Daley Farms, Steve Plath, Gila Watershed Partnership, Morgan Steele, City of Safford, Ryan Rapier, Mt. Graham Regional Medical Center, Mike Crimmins, University of Arizona Cooperative Extension, Carianne Campbell, Sky Island Alliance

Time/Location:

8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. / Eastern Arizona College, 615 N. Stadium Drive, Thatcher, AZ

The annual Upper Gila Watershed Forum on September 28th in Thatcher, Arizona will feature day-long discussion, presentations, and activities focused on “Adapting to a Hotter and Drier Future.” Explore how increasing heat and drought are affecting agricultural, business, municipal, and conservation practices, and what communities and individuals are doing to

adapt. In this interactive forum, participants will:

- Discuss on-the-ground effects of increasingly hotter and drier conditions

- Share adaptations and solutions within the watershed and beyond

- Decide on actions and priorities to support a positive future

- Help create a collaborative approach to adaptation

- Network and build connections

On September 27th, we will tour places where members of our ommunity have experienced and adapted to increased heat and drought. Details to be distributed soon.

Contact evenbrite.com and type in “Upper Gila Watershed Forum” or contact Clara Gauna at clara@gwpaz.org

3. If You Have Spent Time Studying Agrostology, you would have spent time studying

_____. (Answer at bottom of this page).

4. Protect Your Hands with the newest gloves on the market. Made with Kevlar. Get a free sample by calling 1 (877) 295-5911

5. Climate Activists Say Women Are Key to Solving the Climate Crisis. When will everyone else get the memo? Last week’s Global Climate Action Summit (GCAS) in San Francisco resounded with calls for the world to avert global catastrophe by transitioning away from fossil fuels and into a clean energy economy. During the three-day conference, heads of states, policy makers, scientists, and leaders from sectors across society weighed in on how to achieve this momentous goal, with everyone agreeing that the enormity of the task demands a broad diversity of strategies.

But at summit meetings, and a number of affiliate events, some participants expressed frustration over the fact that one key strategy isn’t getting its due. “We have decades of research showing that investing in women’s human rights, including access to education and sexual and reproductive rights, is a significant part of how we can combat climate change” said Bridget

Burns of the Women’s Environment and Development Organization at a forum on Friday morning. “We need to stop seeing this as an add-on to effective climate action and actually as central to it.”

Women are disportionately affected by climate change, partly because its impacts are felt more by the poor, and the majority of people living in poverty are female. For example, 60 percent of those subsisting on less than a dollar a day in Sub-Saharan Africa are women.

Women are also more likely than men to be managing food production for their family—in poorer parts of the world, they produce 60 to 80 percent of food crops.

Giving women farmers the same resources that male farmers receive (for example, the ability to take out small business loans) would improve yields and could reduce the number of hungry people globally by 150 million. Higher yields not only buffer people against the effects of climate change, they also help combat it by easing pressure on natural resources and decreasing deforestation.

Access to reproductive health services is both a fundamental human right and another key to reducing pressure on natural resources. Two hundred and twenty-five million women in low income countries say they want to be able to choose whether and when to become pregnant, but don’t have access to contraception. The result is approximately 74 million unplanned pregnancies each year. Education also reduces birth rates and improves the lives of women and their families in countless ways–for example, female farmers who are more educated have more productive agricultural plots.

Given all of this, some climate activists found the summit’s emphasis on high tech solutions exasperating. “There’s often a focus on techno fixes,” said Burns, “when for years, we’ve been saying that investing in women’s human rights is how we can address climate change. There is still this huge disconnect between the rhetoric and the solutions that are coming from feminists and frontline voices.”

Constance Okollet is one of those frontline voices. She traveled to the summit from her rural community in southeastern Uganda, where villages are already reeling from the impacts of climate change. Farmers grapple with unpredictable weather patterns, storms and droughts destroy crops, and food insecurity is a constant threat. In the face of this, Okollet and other

women in her community formed the Osukuru United Women Network in 2007 (Sierra published a profile of the group last November). Together, they work to diversify their crops, start small sustainable businesses, educate the community about climate change, and promote renewable energy. But lack of funds stymies their efforts. “We need money,” Okollet told Sierra at the summit. She had little patience for its lofty rhetoric, asking in meetings, “What can you give me to carry home?”

Ruth Spencer, who is from Antigua and Barbuda, also attended the summit hoping to garner more support for her country’s efforts to deal with climate chaos. “The impact of climate change, we see it everyday,” she said. The island of Barbuda was decimated by Hurricane Irma more than a year ago and is still struggling to recover. “The last hurricane, it brought so much sand that right now people can not grow any plants to feed their animals. There’s no local food production. The schools have not been repaired.”

As the national coordinator for the United Nations Development Programme’s small grant program, Spencer delivers funds for local projects. “My groups I’m working with, they have big dreams, and they see they have to do something,” she said. “That’s what I’m here to share. Empower the people and things will happen.”

Okollet and Spencer demonstrate what climate activists on the ground have been saying for a long time—women in frontline communities are not just victims of climate change, but possibly our best hope for enabling vast swaths of the global population to mitigate its effects.

For some, the summit encapsulated an even deeper dissonance between what they see as traditional patriarchal power structures that embrace a-business-as-usual response to the climate crisis and the need for a radical overhaul of the systems that caused it in the first place.

Grassroots organizations like the It Takes Roots Alliance and indigenous groups made their voices heard at the Rise for Climate March on the Saturday before the summit, and in the street outside the conference center on Thursday morning

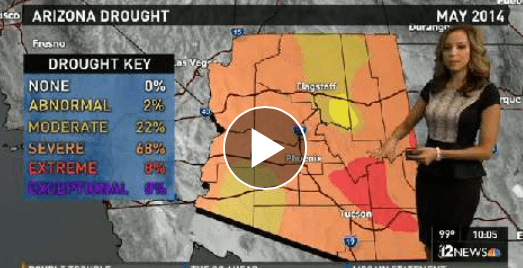

THE DROUGHT IS REAL

Yes, Arizonans have been hearing about the drought for so long it has become background noise, but that’s because the state has had below-normal rainfall levels for so long – all but a few years since 1999. If the monsoon can’t recover, Phoenix could post one of its driest years on record, at least at the official Sky Harbor measuring station, which has collected

just 0.06 inch since June 15. And things have been dry all across the West, from California to the remote peaks in Colorado, which means …

A June story in the Arizona Daily Star outlined the ways Arizona could end up with an official water shortage, but it pronounced the chances of that happening anytime soon to be “slim.”

Within days, the New York Times weighed in with a more dire take. Citing drought projections by the Central Arizona Project — which moves water from the Colorado River to Phoenix and Tucson — an article warned the canal might cut its deliveries to the state’s urban areas as early as 2019.

That opened the floodgates (even if they hold back less water these days) of the idea. Arizona was out of water.

Smithsonian.com posted an item online with the headline “Arizona could be out of water in six years,” linking to the Times story, an Environmental Protection Agency report on climate change and background material. Other online sources followed up.

Suddenly, the Internet was mourning Arizona’s final days.

Not so fast, Arizona’s water experts say. First, projections about shortages on the Colorado River weren’t new. As early as 2004, after a series of record-dry years on the river and across Arizona, CAP hydrologists had started saying the Colorado system might run short by 2015 or 2016. One worst-case outlook pegged the date at 2011. Of course, 2011 came and went, and the Colorado was still running.

The latest data from the U.S. drought monitor suggests Arizona’s monsoon rains have offered some small relief, a 6 percent decrease, from the extreme drought conditions across swathes of Yavapai County and southeast Arizona.

The CAP disputed the Times story. Water agencies in the state tried to reassure residents and businesses that there was no impending crisis.

But then in July, Lake Mead, the giant reservoir that had been dwindling for most of the past decade, finally sank to its lowest level in 77 years. The milestone raised the commotion again.

So, is it time to hightail it out of here? Brace for waterless Wednesdays?

Is Arizona really running out of water?

Yes. And no.

Here are five reasons why the drought should concern you and five more why we’ll survive it — this time:

You should take this drought seriously because:

- The drought is real.

Yes, Arizonans have been hearing about the drought for so long it has become background noise, but that’s because the state has had below-normal rainfall levels for so long — all but a few years since 1999. If the monsoon can’t recover, Phoenix could post one of its driest years on record, at least at the official Sky Harbor measuring station, which has collected just 0.06 inch since June 15. And things have been dry all across the West, from California to the remote peaks in Colorado, which means … - The Colorado River is hurting. It’s true, rain in metro Phoenix doesn’t do much for the water supply, because there’s so little of it that most water is imported from elsewhere. But a lot of that water comes from the Colorado River, which is a source of water for 40 million people in seven states, including Arizona. And the Colorado has seen below-average runoff in all but three years since 2000. Lake Mead has

fallen to its lowest level since it started filling in the 1930s. The other big reservoir on the river, Lake Powell, is half empty. If Lake Mead continues to shrink, current legal compacts lay out how much all seven states have to cut back on water use. Which leads to … - When the Colorado shrinks, Arizona gets burned.

Here’s how the deal among states works, in a nutshell: As Lake Mead gets lower, Arizona has to start cutting back on its take; so does Nevada, which agreed to share Arizona’s pain. California gets to keep its whole share, for as long as there’s enough water on the river. Wait, why does Arizona get such a raw deal? It goes way back to 1968 — Arizonans wanted to build the CAP Canal to take more water but needed California’s congressional support. California agreed, as long as it got to keep the water when things got dicey. So yes, Arizona gets the short end on this deal. On the other hand, if the CAP Canal hadn’t been built, Arizona wouldn’t have been able to get much water out of the river anyway. The canal helped provide for a lot of new growth in Phoenix and Tucson. Some parts of town get water from reservoirs inside the state, but … - In-state supplies are hurting.

Not everything comes from the Colorado — about half of the water supply for metro Phoenix comes from Roosevelt Lake and the Salt and Verde rivers, right? Well, things aren’t much better there. Roosevelt, the largest in-state reservoir, is just 39 percent full. Together, the six reservoirs on the Salt and Verde are at 49 percent of capacity. (By the way, Flagstaff gets a significant share of its water from Lake Mary — it’s shrinking, too, with no change in sight.) All of this means Salt River Project, which manages the system and delivers water to farmers and Valley cities, will likely start to pump more groundwater instead, as will farmers in central Arizona. And you can probably see where this is going … - Groundwater supplies are shrinking at an alarming rate.

A new study by NASA and the University of California-Irvine found the Colorado River basin has lost 41 million acre-feet of groundwater since 2004.

That’s the equivalent of the entire amount of water in Lake Mead when it’s full, plus half of another Lake Mead. Enough to supply the residential water needs of every person in America for one year. Gone. And it doesn’t just come back. Scientists say states pumped from their aquifers to make up for dry years on the river. While one wet year can start to refill a reservoir, groundwater stores can take centuries to recover.

But wait. Don’t panic. Arizona is not in the same beached boat as California, because:

- You might not even notice the cutbacks at first.

If there is a shortage on the Colorado River, the first people to lose it are farmers in central Arizona. Their rights are lowest on the list. Homes and businesses in the three counties served by the CAP Canal (Maricopa, Pinal and Pima) get higher priority. Even under the worst case outlined in the drought plan, about 1 million acre-feet would continue to flow down the canal each year during the shortage,

enough to provide what cities currently take from it. (That’s as long as the river can supply that much water. If things get bad, biblically bad, the CAP would have to shut down. The only people with rights to the very last drops of Arizona’s share are the farmers in Yuma — their rights are the most senior of all.) - We’ve been saving.

A whole lot of the Colorado River water Arizona has taken with the CAP Canal didn’t actually get used — it was poured into underground water banks, sort of like simulating a recharged, natural aquifer. Since 1996, the state has stored about the equivalent of two full years of CAP water. Recovering the water wouldn’t be cheap because it would require construction of wells that don’t exist and would be a one-time fix in some areas, but it would buy time for drought conditions to ease. - We’re getting better at using less.

Water demand leveled off as Arizona and the other states on the river dealt with the recession and downturn in housing. At the same time, requirements to build homes with low-flow plumbing and less landscaping reduced use in the newest developments. - We’re getting better at making it last.

Arizona passed laws in 1980 to protect groundwater supplies in five areas. Since then, it has worked with neighboring states to use water more efficiently, building a reservoir west of Yuma to capture water unused by farmers. And the CAP joined water agencies in Colorado, Nevada and California this summer to provide incentives to cities, businesses and farmers to use less water. - We’d be better off if we got just … one … good … year.

One above-average runoff year on the Colorado River or on the Salt and Verde rivers could buy Arizona more time to prepare for shortages. Reservoirs have briefly recovered some of their losses during the 15-year span; Roosevelt Lake can, in theory, refill in one wet year — that alone could mean a few extra years of supply.

Still, experts say the West needs to address its water-supply issues soon. Studies show that overall temperatures are rising. That means less snowpack or shorter runoff seasons. That means lower river flows. The groundwater study shocked many water agencies because it revealed huge losses. And it underscored the fact that the states have often drawn more water from the river than annual runoff can

replenish.

So yes, Arizona is running out of water — just the way it was when it built the Central Arizona Project, the same way it was when it passed the groundwater-protection laws. It’s highly unlikely that anything dramatic will change for most Arizonans in the next six years. There’s a lot of water left out there. But only time and people’s decisions will tell if it’s enough.

Argostology – Grasses