1. Why ‘Cloud Seeding’ Is Increasingly Attractive to the Thirsty West. Machines that prod clouds to make snow may sound like something out of an old science fiction movie. But worsening water scarcity, combined with new proof that “cloud seeding” actually works, is spurring more states, counties, water districts and power companies across the thirsty West to use the strategy.

Last month, a study funded by the National Science Foundation proved for the first time that the technology works in nature. That study, combined with other recent research, has helped make cloud seeding an attractive option for officials and companies desperate to increase the amount of water in rivers and reservoirs.

In Colorado alone, more than a hundred cloud seeding machines are set up in mountainside backyards, fields and meadows. Some older versions of the contraptions look like a large tin can perched on top of a propane tank. New ones are large metal boxes festooned with solar panels, weather sensors and a slim tower.

Their goal is the same: to “seed” clouds with particles of silver iodide, a compound that freezing water vapor easily attaches to. That makes ice crystals, which eventually become snowflakes.

Colorado’s $1 million a year program has been around since the 1970s and is paid for not just by the state, ski resorts, and local water users but also water districts as far away as Los Angeles that want to increase snowmelt into the Colorado River, which sustains over 30 million people across the Southwest. Currently, most of the river basin is experiencing a drought.

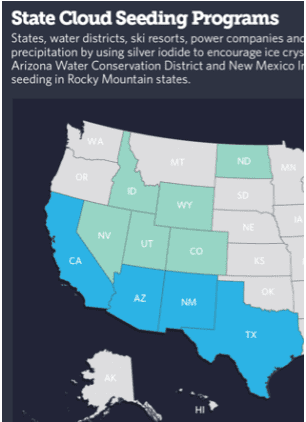

Major urban water districts in Arizona, California and Nevada have funded cloud seeding in the Rocky Mountains for over 10 years and are now close to signing an agreement with officials in Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming to split the cost of nine more years of seeding.

Cloud seeding is a relatively cheap tool for bulking up the water supply in Lake Mead and other reservoirs, said Mohammed Mahmoud, a senior policy analyst for the Central Arizona Water Conservation District. The up to $500,000 annual commitment the district is making to the regional agreement comprises a tiny fraction of its budget, he said.

A 20th Century Technology

Scientists discovered in the 1940s that certain molecules make a good foundation for snow. In one famous experiment, a chemist made it snow by dumping six pounds of dry ice out of an airplane over western Massachusetts.

It didn’t take long for states, localities and ski resorts to start experimenting. Colorado’s Vail ski area began cloud seeding in the 1970s, for instance. Today California, Idaho, Nevada, Utah and Wyoming have winter cloud seeding programs, and Texas and North Dakota have summer program which aim to increase rain and decrease hail

Nevada’s cloud seeding program can increase the snowpack by up to 10 percent, McDonough said.

That translates into 80,000 more acre-feet a year of water, enough to sustain about 150,000 households.

Still, he said, cloud seeding programs are difficult to evaluate. “Ten percent of additional snowfall is within the natural variation of storms.”

Although it’s hard for scientists to gauge the effectiveness of cloud seeding, many water districts are willing to take a chance on the technology because cloud seeding is relatively cheap.

The Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ) has made available a Sampling & Analysis Plan (SAP) template for permittees of the Multi-Sector General Permit (MSGP), consultants and other interested parties. The template can be modified in a word processor, and once completed shall be maintained with the Stormwater Pollution Prevention Plan at the facility (and submitted to ADEQ depending on specific requirements). The final page of the SAP template, titled Stormwater MSGP Sample Collection Form, is also available individually for additional stormwater sample collections.

3. Restrictions Won’t Affect All Users Of Colorado River Water. BULLHEAD CITY — As water levels in Lake Powell and Lake Mead drop, the potential for restrictions on water use in 2019 rise, but not for all Colorado River water users.

Under the 2007 drought plan guidelines Arizona adopted, Central Arizona Project will take the full hit for whatever that reduction is, said Mark Clark, Mohave Valley Irrigation and Drainage District manager.

CAP’s hit, Clark said, is about 349,000 acre-feet of water.

“The local folk here along the river really won’t see any change due to a shortage declaration at a tier one level,” Clark explained.

In August, Bureau of Reclamation releases its 24-month study and projects out to January of 2019 whether or not Lake Mead is going to be at an elevation of less than 1,075 feet, Clark said.

“If Lake Mead is going to be at less than an elevation of 1,075 feet, a tier one shortage would be declared,” Clark said. “If it got below 1,050 feet — and the likelihood of that is pretty remote — a tier two shortage would be declared. But the likelihood of a tier one shortage declaration is pretty realistic right now.”

Arizona Department of Water Resources recently reported the entire Southwest has experienced one of the warmest, driest winters on record; snowpack in the mountain regions, which provide runoff into reservoirs like Lake Powell and Lake Mead may be at record lows.

Based on the current snow-water equivalent graphs, it is a very real possibility that snow water equivalent is tracking lower than 2002, which was the lowest year in recorded history for 100 years of records, Tom Buschatzke, Arizona Department of Water Resources director said in an interview with Arizona Water News, the official news blog of the ADWR.

That loss of volume of water represents close to 10 feet of elevation in Lake Mead, Buschatzke said. The BOR’s current projection —the 9 million acre-foot release — is about 5 feet above the shortage trigger, which means that if instead only 8.23 million acre feet is released, the elevation would be 5 feet below the shortage trigger.

“If we can’t conserve enough water in Lake Mead to make up the difference, that will be a high bar to achieve between mid-April and the end of July, which would be the time period in which we’d have to do the conservation,” Buschatzke said.

For the past few years, the state has participated in negotiations on an updated plan known as the Drought Contingency Plan — which has not yet been signed — that would require states like California and Nevada to make earlier and deeper cuts to protect Lake Mead’s current water level, as well as an enhanced plan known as Drought Contingency Plan Plus, signed in 2017, an Arizona-based plan to help stabilize Lake Mead Water levels.

“DCP plus actually calls for more reductions before a shortage is actually declared, so that we can try and stay out of shortage, Clark said. “We were hopeful DCP was going to be signed last year, but the wheels came off the tracts a little bit and it wound up not getting signed. In fact, they’re getting further apart now than they were last year.”

Clark believes water entities, including MVIDD, will make voluntary cutbacks this year to try and keep water in Lake Mead.

“The problem with these types of voluntary programs has always been, who owns that water,” Clark said. “If we volunteer to put water behind the dam, we don’t want to do it then have somebody else down the river takes it because we didn’t use it. We want to be sure that if we volunteer to not use water it stays behind the dam and doesn’t get used by somebody else.”