Daniel Salzler No. 1290

EnviroInsight.org Four Items January 24, 2025

—————Feel Free To Pass This Along To Others——————

If your watershed is doing something you would like others to know about, or you know

of something others can benefit from, let me know and I will place it in this Information .

If you want to be removed from the distribution list, please let me know.

Please note that all meetings listed are open.

Enhance your viewing by downloading the pdf file to view photos, etc.

The attached is all about improving life in the watershed through knowledge.

If you want to be removed from the distribution list,

please let me know. Please note that all meetings listed are open.

Check our website at EnviroInsight.org

- Arizona Tribal Nations Receive $121 Million Boost For Climate Resilience From Federal Funds.

Five tribal nations in Arizona received funding from the U.S. Department of the Interior to help their communities prepare for the most severe climate-related environmental threats to their homelands.

“Indigenous communities face unique and intensifying climate-related challenges that pose an existential threat to Tribal economies, infrastructure, lives and livelihoods,” Secretary of Interior Deb Haaland said in a written statement.

The funding is part of Interor’s Tribal Community Resilience Annual Awards Program, which funds federally recognized tribes and tribal organizations to build community resilience capacity.

In Arizona, the Kaibab Band of Paiute Indians, Navajo Nation, San Carlos Apache Tribe, Zuni Tribe and Yavapai Prescott Indian Tribe all received money to help their communities plan and implement climate-related projects.

The funding comes from the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act, Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and annual appropriations. The Department of Interior stated that the investment helps tribal nations plan for and adapt to climate threats and safely relocate critical infrastructure as needed.

“Through President (Joe) Biden’s Investing in America agenda, we have made transformational commitments to assist Tribes and Tribal organizations as they plan for and implement climate resilience measures, upholding our trust and treaty responsibilities and safeguarding these places for generations to come,” Haaland added.

“Today, we are not just investing in projects; we are investing in the future of our Tribal communities,” Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland said in a statement.

The money will support both planning and implementation of projects, including climate adaptation planning, community-led relocation, managed and partial relocation, protect-in-place efforts, ocean and coastal management, and habitat restoration and adaptation.

“The Biden-Harris administration recognizes the vital role that Indigenous knowledge and leadership play,” Newland said. “These awards are a downpayment on a more sustainable and resilient future for Native communities across the country.”

The Kaibab Band of Paiute Indians, Navajo Nation, San Carlos Apache Tribe, and Zuni Tribe were awarded funding in the program’s planning category, giving tribes more flexibility in addressing their climate concerns.

In northern Arizona, the Kaibab Band of Paiute Indians’ tribal land runs along the Utah border near Fredonia; they received $249,789 to support the development of a climate change adaptation plan to address the drought, temperature extremes and wildfire risks facing the Kaibab Band of Paiute Indians.

“The plan will enhance the Tribe’s climate resilience by protecting water resources, cultural sites, and community health while supporting long-term economic sustainability,” according to the program summary.

The Navajo Nation received $249,820 to support the Teesto Chapter House, located 45 minutes north of Winslow, with climate resilience planning.

The project will create a climate resilience plan for the Teesto Chapter House through community engagement, climate vulnerability assessment and prioritization of adaptation actions.

“The plan will strengthen the community’s ability to address climate impacts, enhance long-term sustainability, and support the development of resilient infrastructure and ecosystems in the southwestern Navajo Nation,” according to the program summary.

For the San Carlos Apache Tribe in southeastern Arizona, the $249,600 it will receive will help with climate resilience planning. As part of their project, the tribe will work with diverse departmental and subject matter experts, including Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge holders, to create a natural, cultural and infrastructure-based climate threat and prioritization action plan.

The tribe will work on reviewing existing plans, gathering member concerns around climate threats within their community, and identifying values at risk and ways to respond. Information collected from these steps will guide the tribes’ response.

In northeastern Arizona, the Zuni Tribe will work on a project focusing on the climate-resilient restoration of riparian wetlands along the Little Colorado River on the tribe’s sacred lands west of St. Johns.

The tribe was awarded $250,000 through the program to develop a comprehensive plan to revitalize native plant and animal species, improve water availability and continue cultural practices.

The project description stated that it would enhance the area’s climate resiliency by creating a sustainable ecosystem that supports biodiversity and the Zuni Tribe’s climate heritage.

The final project awarded is part of the implementation category of the project, and the Yavapai Prescott Indian Tribe was awarded over $3.1 million to support the tribe’s water sovereignty and quality improvement efforts. Their tribal land is located east of Prescott.

The project description states that the tribe aims to improve water quality and restore habitats along Granite Creek by mitigating harmful runoff from overwhelmed drainage systems upstream of the Frontier Village Shopping Center and Slaughterhouse Gulch.

“Improvements will advance the Tribe’s ongoing efforts to increase water sovereignty on reservation lands,” the program summary states. Source: PinalCentral news January 13, 2025

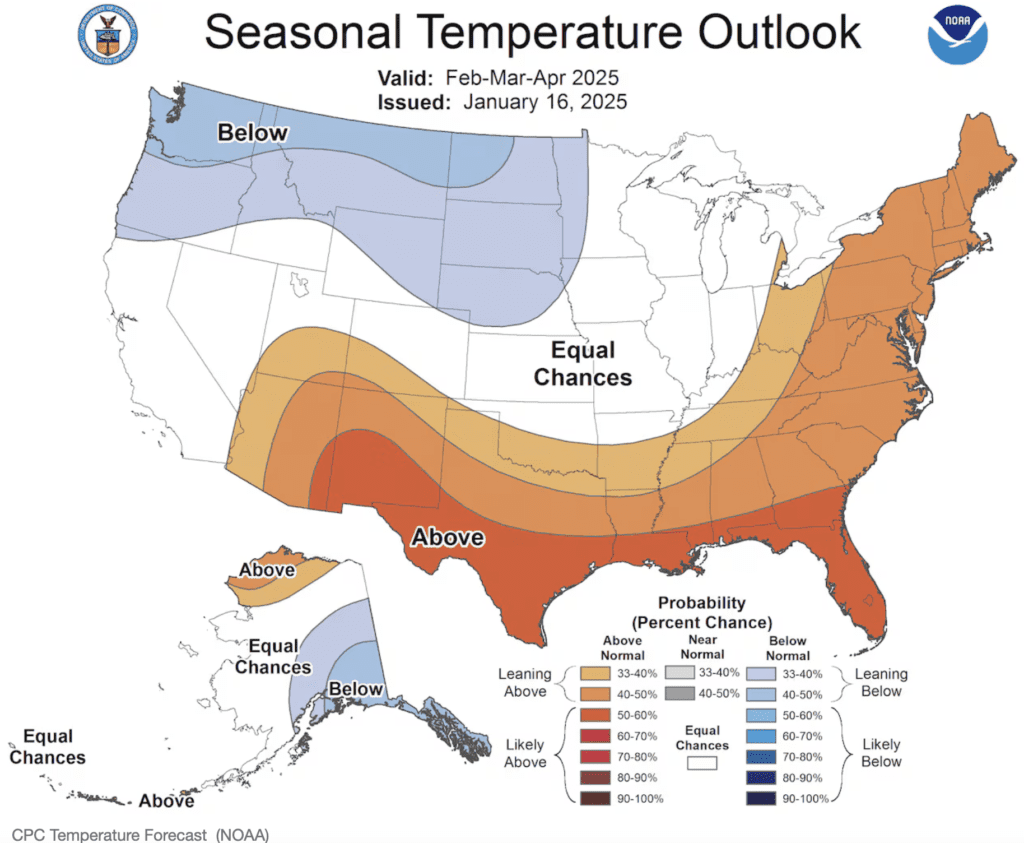

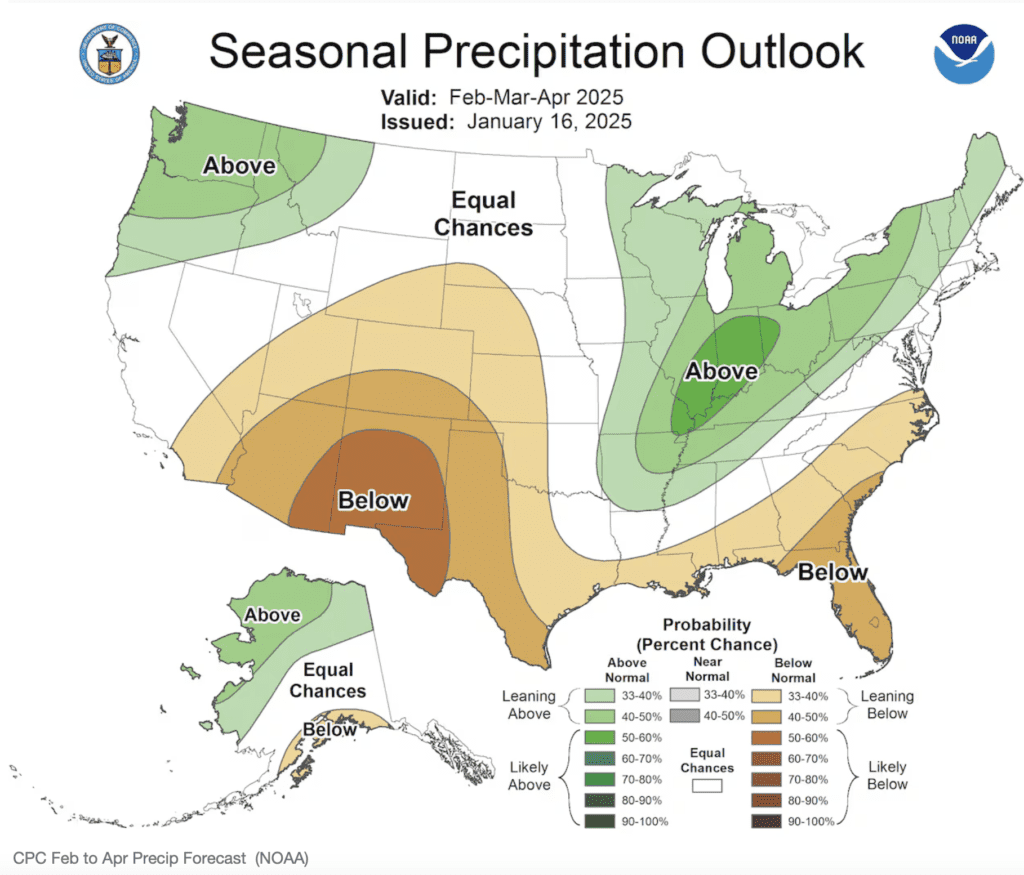

2. Future Climate Outlook. The Climate Prediction Center issued its new forecast for February through April. It’s not great news if you are a snow-lover in Arizona, but these longer-term forecasts always have high uncertainty and are not set in stone.

From February through April, the CPC is leaning warmer than normal in Arizona. However, they only forecast this with a 33% to 50% confidence. For southeast Arizona, they are forecasting warmer-than-normal temperatures with a 50% to 60% confidence.

For precipitation, the CPC is leaning drier than normal in Arizona. They are doing this with a 33% to 50% confidence for most of Arizona but a 50% to 60% confidence in southeastern Arizona.

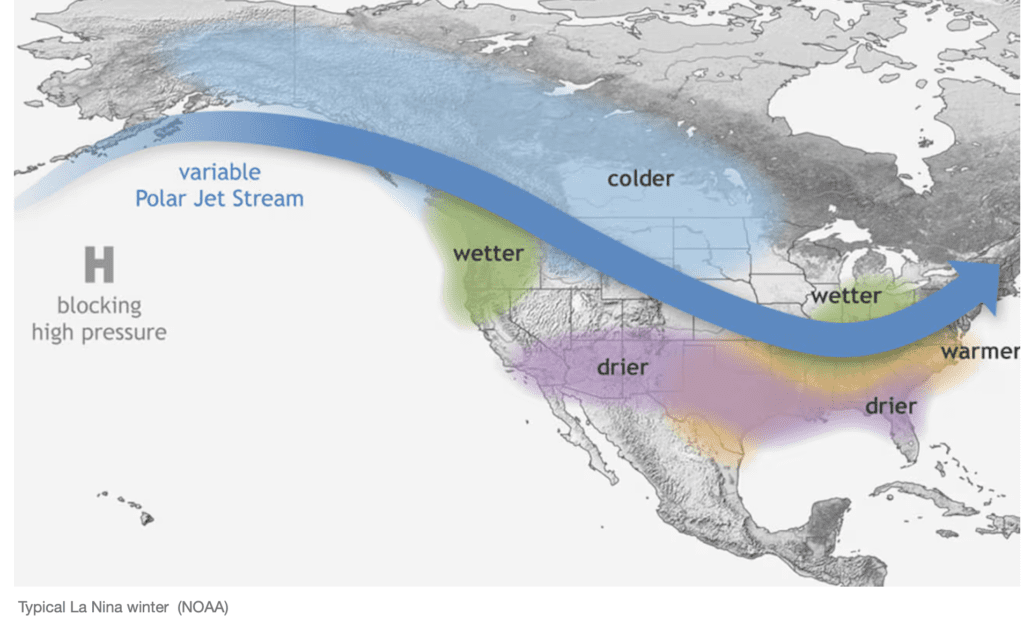

So, what are the reasons behind this forecast? One of many tools that long-term forecasters use is the state of El Niño, La Niña, or neutral conditions. Right now, La Niña is in place, and it may stick around for a bit. The map below shows what “typically” happens during La Niña winters.

In the two maps above, notice the similarities between a “typical” La Nina winter and the forecast for February through April. The state of La Nina is not the only tool used to make the forecast, but it is an important part of this prediction. Finally, not all La Nina(s) behave the same, and sometimes they go against the “typical” trend. Source: Pete Mangione, AZ Famy.

3. Colorado River Snowpack Offers Little Hope To End Water Cutbacks In Arizona In 2026. Austin Corona, Arizona Republic

Snowpack in the upper Colorado River basin is slightly less than normal for this time of year, meaning Arizona could see sustained water cuts through 2026.

Though trends could change through the rest of the winter, the snowpack in the basin is about 94% of the median for mid-January. While Arizona’s share of Colorado River water in 2025 is already set, the snowpack numbers are early indicators of how much river water the state could get next year.

Even with an average snow year, water managers say dry conditions and warming temperatures could create below-average runoff, keeping Arizona water users in shortage.

Arizona relies on snowmelt for much of its water supply. About 36% of the water used in Arizona’s households, businesses and farms comes from the Colorado River, mostly comprising melted snow from mountainous areas in Colorado, Wyoming and Utah. Arizona’s water managers can watch snow conditions using a network of snowpack measurement sites operated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Nolie Templeton monitors Colorado River supplies for the Central Arizona Project, a 336-mile canal system that brings Colorado River water to areas around Phoenix and Tucson. Templeton said this winter has been abnormally dry for southern areas of the basin like Arizona and New Mexico, but northern areas have received normal precipitation. That snow, falling as far away as Wyoming, will provide Arizona’s water in coming years.

Even with average snowfall, Templeton said, Arizona might not get relief from recent shortages on the river. Projections of how much snowmelt will run down the river this year have declined since early December, reflecting a lack of snow and shifting weather patterns in the Pacific Ocean. Government scientists now project that the basin will see roughly 82% of its normal runoff this year, down from a projection of 90% in December. “What we’ve seen, based on drying conditions and higher temperatures is that about-average snowpack means below-average runoff,” Templeton said.

Planning for cuts:Colorado River states fear a long legal battle as talks falter over shortage rules

‘We’re planning for less flow in the Colorado River’

Even when the snowpack is strong, other factors can keep that snow from turning into river runoff. Dry soils, human water use and sublimation (a process where snow and water are lost to the atmosphere) can all soak up snowmelt before it flows to Arizona. Templeton said the effects of climate change could be increasing those losses.

In 2024, the basin saw peak snowpack about 5% above the median, but runoff was 17% below the median. While 2023 had huge snow (50% above normal) runoff exceeded its median by a smaller amount (40%).

“We’re learning more every day, but what we’re learning is that when precipitation falls on the watershed, it’s not as efficient as it used to be,” Templeton said. “We’re seeing higher temperatures impacting our hydrological cycle. We’re planning for less flow in the Colorado River. That’s not to say there won’t be periods of high flow here and there.”

That reduced runoff means less water for Arizonans. The water levels in the river’s second largest reservoir, Lake Powell, largely dictate how much water is released to lower basin states like Arizona. Federal dam managers already used existing guidelines in 2024 to determine Arizona’s share of the river for 2025, so the snowmelt flowing into the reservoir this year will define Arizona’s share in 2026.

Based on rough projections available this year, Arizona will likely remain under existing cuts to its Colorado River use. Under the conditions of several interstate agreements, Arizona has operated under a “Tier 1 shortage” on the river since 2022, a result of drought and overuse that have strained the Colorado. Under the cuts, Arizona has given up about 8% of its previous water supply, according to the Arizona Department of Water Resources.

The basin could still get a big influx of snow this winter, Templeton said, a scenario that played out in 2024. Pacific ocean temperatures, which have a strong effect on weather patterns in North America, have shifted toward a brief “La Niña” condition this winter. Templeton said the La Niña pattern has no strong correlation with precipitation in the upper Colorado River basin, so it’s hard to tell whether the river will get a late-winter dump of snow.

“It just takes a couple of really big storm events, and you get above that median. It’s yet to be determined if we get those events in 2025,” Templeton said.

While early projections can be somewhat useful, Templeton said it is still too early to know exactly how the snow year will shake out. “We’re right around the median,” Templeton said. “However, we have a lot of snowfall season left to go, and we don’t know how it’s going to go.”

Dry conditions:What will it take to end 3 decades of drought in Arizona?

How much snow has fallen in Arizona?

Within Arizona, river basins have received almost no snow. The snow-fed Salt and Verde rivers, which provide about a quarter of the Phoenix area’s water, both stand at less than 10% of normal snowpack for this time of year.

This is probably one of the basins’ driest early winters in 100 years, though the historical data isn’t good enough to confirm that.

SRP, a reservoir and canal network that delivers Salt and Verde water to users in the Phoenix area, will rely on groundwater and existing supplies in its reservoirs to make it through the dry year, Svoma said. SRP reservoirs were about 70% full as of Jan. 14.

Svoma said water users probably won’t see the effects of this dry year anytime soon. Reservoirs would have to drop to 30% of capacity before managers get concerned and start implementing water cuts. It would take two more hot, dry summers and another bone-dry winter before reservoirs could drop that low, Svoma said.

SRP reduced water deliveries in 2003 and 2004 after a sustained drought drew reservoirs to precariously low levels.

The basins could see a big surge of snow later in the winter, but that hasn’t happened in recent years. Without massive precipitation, desiccated soils will soak up whatever moisture Arizona does receive for the rest of year, Svoma said.

“We’re really facing an uphill battle right now for getting a good runoff season into the reservoirs,” Svoma said.

4. New Maximum Civil Penalties for Environmental Violations Posted on 1/8/2025 by Lion Technology Inc.

On January 8, 2025, the US EPA increased its maximum monetary civil penalties for violations of air, water, chemical, and hazardous waste programs. The Agency is required to raise civil penalty on or After 1/8/25

| Major US EPA Programs | Before 1/8/25 | On or After 1/8/25 |

| Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) | $90,702 | $93,058 |

| Clean Air Act (CAA) | $121,275 | $124,426 |

| Clean Water Act (CWA) | $66,712 | $68,445 |

| Superfund and Right-to-Know (CERCLA/EPCRA) | $69,733 | $71,545 |

| Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) | $69,733 | $71,545 |

| Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) | $48,512 | $49,772 |

| Insecticides, Fungicides, and Rodenticides (FIFRA) | $24,255 | $24,885 |

The new maximum penalty listed above for a first-time CERCLA violation is $71,545, The new maximum penalty for a subsequent CERCLA violation is $214,637, up from $209,202.

Copyright 2025: EnviroInsight.org