Daniel Salzler No. 1287

EnviroInsight.org Three Items January 3, 2025

—————Feel Free To Pass This Along To Others——————

If your watershed is doing something you would like others to know about, or you know

of something others can benefit from, let me know and I will place it in this Information .

If you want to be removed from the distribution list, please let me know.

Please note that all meetings listed are open.

Enhance your viewing by downloading the pdf file to view photos, etc.

The attached is all about improving life in the watershed through knowledge.

If you want to be removed from the distribution list,

please let me know. Please note that all meetings listed are open.

Check our website at EnviroInsight.org

- Happy New Year!

2. A Turbulent Year On The Colorado River Comes To A Close.

This year was a bumpy ride for the Colorado River. As 2024 comes to a close, we’re look ing at the stories that defined the water supply for 40 million people. Deep divisions between policymakers set the stage for deep uncertainty from Wyoming to Mexico, and those who use Colorado River water are hoping for some more clarity in the years to come. But with an unpredictable new president heading to the White House, they may end up with more questions than answers.

Early disagreement

The biggest headlines of the year came early on the calendar. In March, seven states that use the Colorado River laid bare the deep divisions between them. The rules for sharing its water expire in 2026, and state leaders are under pressure to agree on new guidelines.

Instead of agreeing, they split into two camps and released competing proposals for managing water. The river is shrinking due to climate change, and states need to rein in their demand. Who exactly should cut back on their water use, though, is at the heart of their disagreement.

Shortly after the two state proposals, a group of native tribes released their own suggestions for managing the river. A coalition of conservation groups did the same.

Paying for conservation

Discord between the negotiators shaping the river’s future highlighted the need for farm districts and cities to get their own houses in order. Agriculture uses between 70-80% of the river’s water, and much of the pressure to conserve the river falls on farms and ranches.

From the river’s single largest water user in Southern California to tiny family farms in rural Wyoming, the federal government experimented with programs that paid farmers to use less water.

In the Imperial Valley, about two hours inland from San Diego, the farm district inked a deal to take more than $500 million from the Inflation Reduction Act. In exchange, the area’s farmers would leave some water in the nation’s largest reservoir, Lake Mead.

Meanwhile, a smaller program in the Colorado River’s Upper Basin states – Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico did something similar. It paid farmers and ranchers to cut back on water use, but some policy analysts say the program lacks a clear plan for the future.

Cities prepare a drier future.

Cities and suburbs, especially in the driest parts of the Colorado River Basin, are taking matters into their own hands. In an effort to buy some certainty against a future that might see their water allocations get smaller, municipal leaders in Arizona chipped away at multibillion-dollar engineering projects to stretch out their existing water supplies.

In the Phoenix area, cities large and small worked towards a dam expansion that would help them capture more snowmelt from mountains to the north. Some made progress on “water recycling” facilities that can clean up sewage and turn it back into drinking water. Similar efforts are underway in other states, too.

Canyons come back.

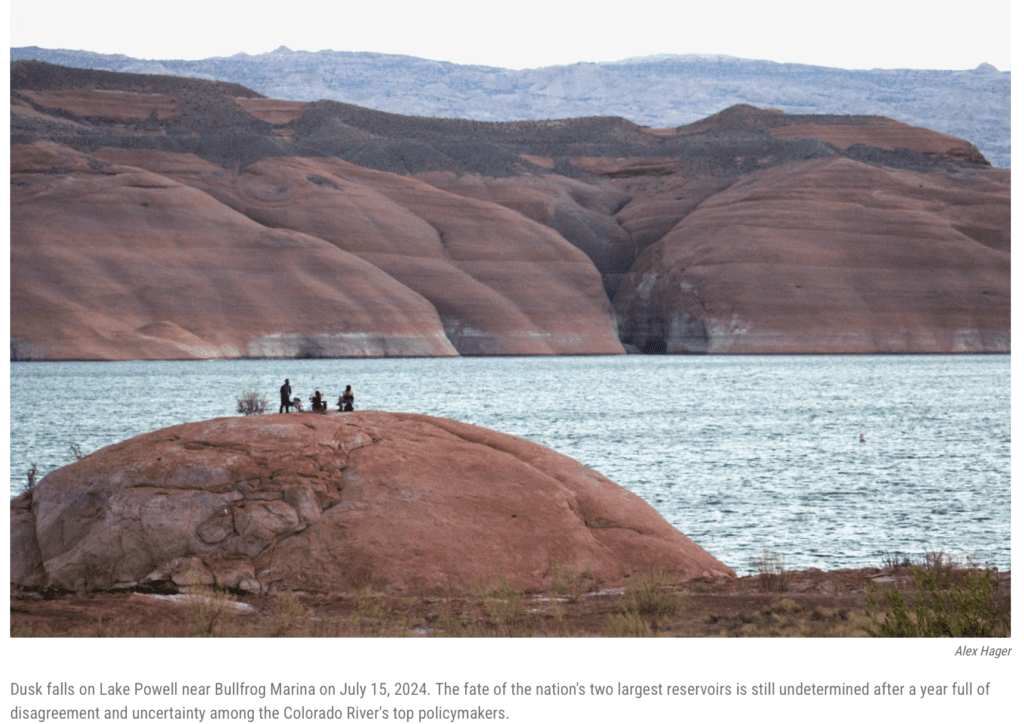

The past few years have seen dramatically low water levels at the nation’s two largest reservoirs – Lake Mead and Lake Powell – which are both filled by the Colorado River. While that has caused concern for the water managers who want to keep taps and crop sprinklers flowing across the region, some environmental advocates are celebrating the return of habitats that had been submerged for decades.

Now that some portions of Lake Powell have been above water for more than 20 years, scientists are able to study the kind of plants and animals that are repopulating the once-underwater canyons. One study found that it’s mostly native vegetation coming back.

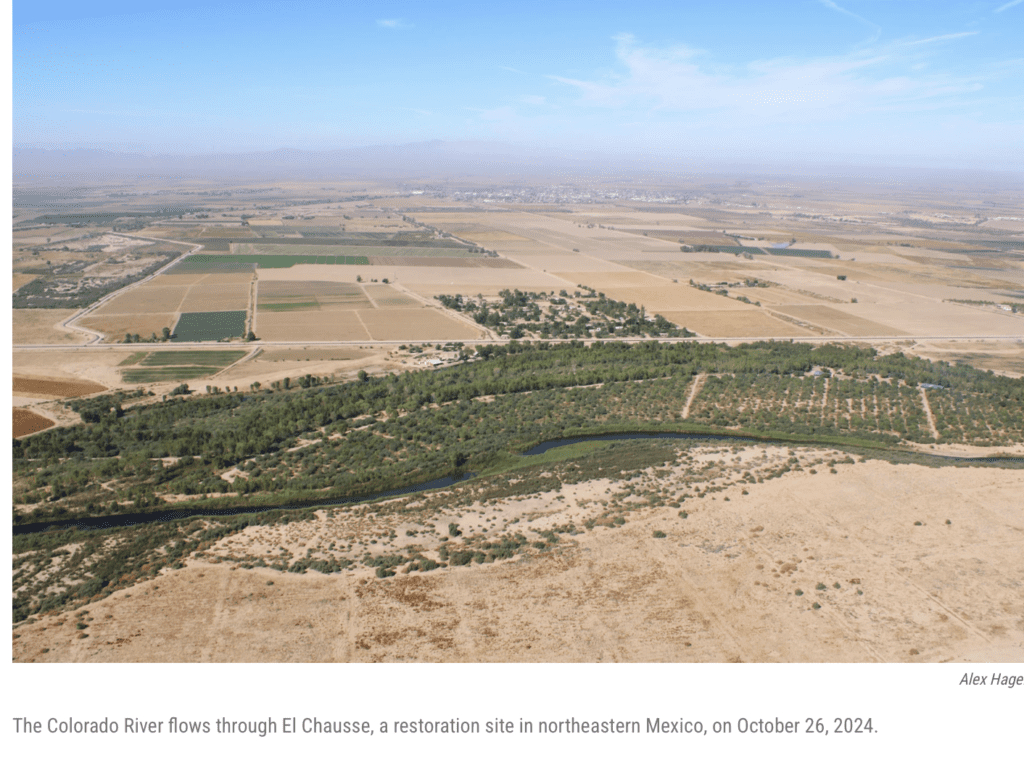

Mexico waits for more water. Uncertainty over the river’s future doesn’t stop at America’s border. In the Colorado River Delta, where the river once reached the sea, environmental groups have created islands of green in the middle of an otherwise barren, dusty landscape.

The future of those oases depends on negotiations between the U.S. and Mexico. In the past, they’ve designated water specifically for ecological restoration. Conservationists hope they’ll do the same again.

Looking into the past and the future.

While this year’s tense negotiations generated frequent headlines about the river’s present, 2024 also provided an opportunity to see how today’s talks are influenced by the past.

A major point of contention between the rival groups of states hinged on the language of a 1922 legal agreement about sharing water. Three words written over a century ago are still shaping the nature of discussions over the river’s future.

Meanwhile, some people watching the negotiations are keeping up a steady drumbeat of calls for ambitious new engineering projects that would secure more water for the Colorado River’s future. The tantalizingly simple solution of piping water from the eastern U.S. to the West just won’t seem to go away, but water experts broadly agree that it’s impractical.

Frustration in the basin

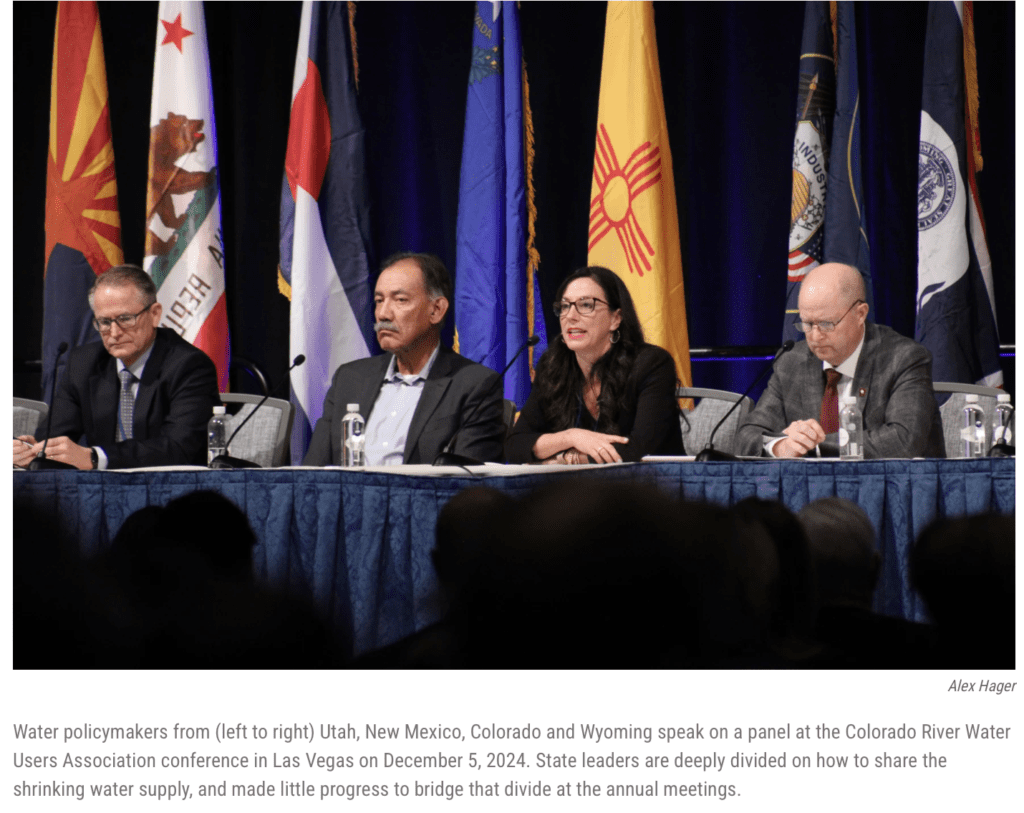

In December, after state leaders had been entrenched in disagreement for months, many involved in Colorado River management grew frustrated. Some commentators voiced those feelings to KUNC ahead of the biggest annual occasion on the Colorado River calendar – a series of meetings in Las Vegas where the public can hear directly from top negotiators.

“I find it really frustrating to watch them just continue to bicker back and forth rather than coming up with any realistic solutions for the problems that we’re facing,” said Teal Lehto, an environmental activist who goes by WesternWaterGirl on social media.

A Las Vegas showdown

At those meetings in Las Vegas, states made little progress in their negotiations, still mostly sticking to the same points they unveiled in their march proposals. States shared stern words and talked of compromise, but struggled to find common ground.

Awaiting change in the White House.

As the year comes to a close, Donald Trump’s return to the White House poses a big question mark for those with a stake in the Colorado River. State negotiators say they do not expect the administration change to shake up their talks, pointing to a pattern of previous presidents leaving water management work mostly to technical experts.

At the same time, some water users worry that Trump may cut spending for water-saving programs that have helped boost the nation’s largest reservoirs during the past few years. Without the federal spending that was set aside by the Inflation Reduction Act, water managers may be forced to come up with new water conservation strategies in 2025.

This story is part of ongoing coverage of the Colorado River, produced by KUNC in Colorado and supported by the Walton Family Foundation. KUNC is solely responsible for its editorial coverage. Copyright 2024 KUNC

3. These Trees Found Around Arizona Can Cool Themselves Down, But Research Reveals They’re At Risk.

While Fremont Cottonwoods have adapted to cool themselves down, even in Arizona’s extreme heat, water access is crucial.

PHOENIX — Amid the Arizona heat, researchers are finding Fremont Cottonwood trees can cool themselves down, but their survival depends on consistent water access.

The trees essentially sweat – using water accessible to the trees to cool their leaves down.

“The effect of that is that their leaves are up to five to 10 degrees cooler than the air temperature,” Brad Posch, PhD said.

Posch is a post-doctoral research scientist at the Dryland Plant Ecophysiology Lab at the Desert Botanical Garden, who led a recently published study conducted with collaborators from Northern Arizona University.

The study demonstrates that the trees have adapted to Arizona’s extreme heat and drought. However, they depend on water to do so.

In the summer of 2023, researchers set out several groups of Fremont Cottonwoods from different Arizona climates at the Desert Botanical Garden. The study revealed just three days of water cutbacks was enough to severely impact the trees’ cooling abilities.

“That was enough to completely disrupt their really efficient cooling mechanism,” Posch said. “What that led to were their leaves getting really, really hot – hotter than those really high air temperatures – and actually hot enough to start causing internal damage to the metabolism and the physiology of the leaf.”

The trees brought in from Arizona’s hottest regions were most effective at cooling off their leaves.

“But that came at the cost of being closer to the point at which they experience damage from drought stress,” Posch said.

Drought and heat have already been shown to have led to Fremont Cottonwoods dying off, as they depend on steady access to water.

“We’re experiencing the rapidly changing climate,” Posch said. “We’re seeing not just increases in the average temperatures around the globe, but we’re also seeing with that hotter heat waves, longer heat waves, and heat waves that occurring more often.”

Amid the extremes, the Fremont Cottonwoods are considered foundational in the ecosystem, Posch said.

“These trees play a really important role as a refuge for migratory birds,” Posch said. “If these trees are threatened, then the birds often face a problem as well.”

As for what can be done to help the trees, Posch said water management will be important.

“Decisions about how we manage water in these habitats where these trees occur could be really, really important in determining whether these populations can survive these hotter – longer and hotter – summers that we’re looking at in the coming decades,” Posch said. Source: 12 news.com

Copyright: 2025 EnviroInsight.org