Daniel Salzler No. 1269

EnviroInsight.org Five Items August 30, 2024

—————Feel Free To Pass This Along To Others——————

If your watershed is doing something you would like others to know about, or you know

of something others can benefit from, let me know and I will place it in this Information .

If you want to be removed from the distribution list, please let me know.

Please note that all meetings listed are open.

Enhance your viewing by downloading the pdf file to view photos, etc.

The attached is all about improving life in the watershed through knowledge.

If you want to be removed from the distribution list,

please let me know. Please note that all meetings listed are open.

Check our website at EnviroInsight.org

1. Solar-Paneled Canopies Over Canals Catching On In Southwest. Western Water Notebook: Photovoltaic Shades Cut Evaporative Losses, Produce Clean Electricity.

An intensifying but unseen force is stealing precious water from rivers in the arid West, but it’s hardly a thief in the night.

The midday sun is one of the more aggressive guzzlers of the Colorado River. Between its high Rockies headwaters and its Sonoran Desert delta, 1 to 2 million acre-feet of water evaporates each year in the Colorado River Basin. That’s a big gulp in a watershed where seven thirsty U.S. states and northern Mexico skirmish for their share of an over allocated, shrinking water supply. And the evaporation will only increase as the Southwest grows hotter and drier.

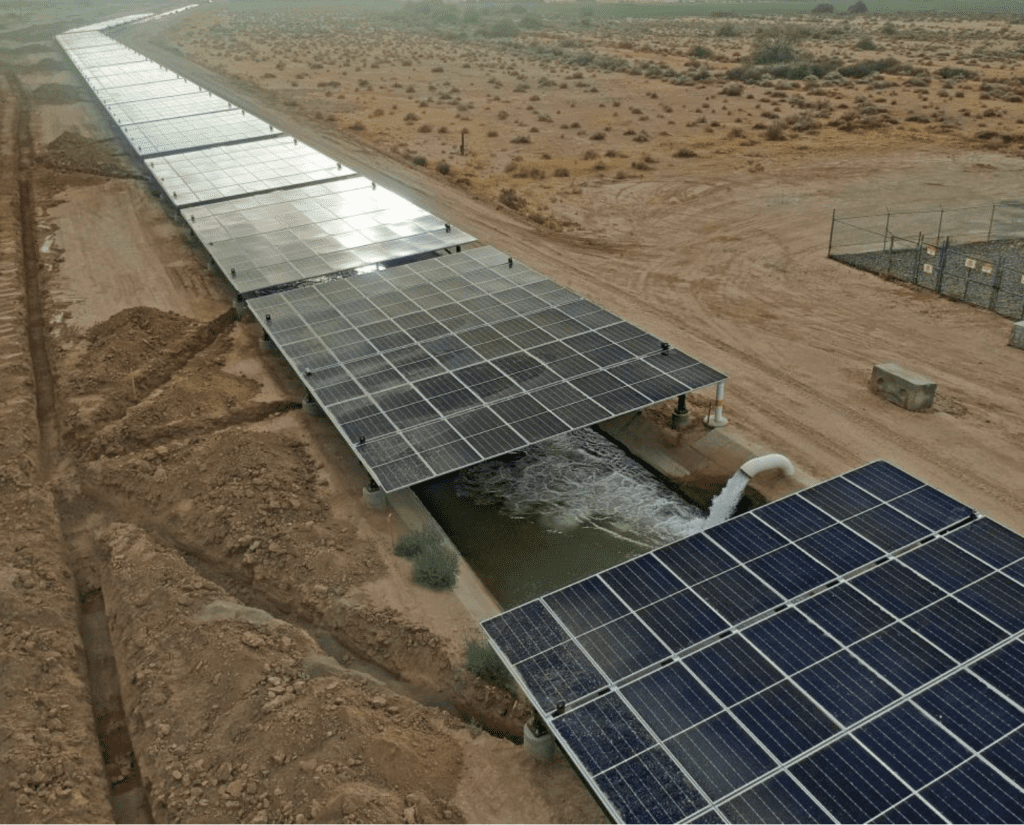

To cut their losses, a growing number of Western water managers want to install solar-paneled canopies over canals and even flotillas of solar panels on reservoirs to turn the sun’s rays into electricity before they hit the water.

“We believe this is the next step in the future of generating renewable energy,” said David DeJong, director of Arizona’s Pima-Maricopa Irrigation Project, which has partnered with the Gila River Indian Community to shade a half mile of the Casa Blanca Canal on tribal land. The pilot project, set for operation by mid-October, could reduce evaporation 50 to 70 percent, he said.

Advocates of the technology cite the multiple benefits of saving water, generating clean energy and helping keep farmland in production. But there are also great costs and engineering challenges associated with covering waterways with solar panels. The wider the canal, and the more distant it is from transmission lines, the higher the price tag and the narrower the benefit margin. In fact, some water supply experts doubt significant gains are to be had.

“The reason you don’t see [solar-shaded canals] everywhere is that it’s just not usually worth it,” said Jeffrey Kightlinger, a water and energy consultant and the former general manager of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California.

Others think the pros clearly outweigh the cons, especially when less obvious benefits are considered. For example, shading or covering canals and reservoirs with solar panels slows aquatic photosynthesis and the growth of algae, which can foul water quality. Moreover, having cool water flowing beneath solar panels maintains their efficiency, which wanes in extreme heat.

The 2,600-paneled solar system under construction on the Gila River Indian Community near Phoenix is on track to be the first solar array over a canal in the Western Hemisphere. Funded by a $5.65 million grant from President Biden’s Investing in America Agenda, the project is expected to keep about eight acre-feet of water in the system each year that otherwise would evaporate, DeJong said. That’s enough to irrigate two acres of farmland or support 15 to 20 households a year.

Eventually, solar canopies could be installed on 16 miles of the Casa Blanca Canal, saving 360 acre-feet of water annually from evaporation and generating about 26 megawatts of power. The project, DeJong said, could make the Gila River Indian Irrigation and Drainage District the world’s first modern carbon-neutral irrigation project.Eventually, solar canopies could be installed on 16 miles of the Casa Blanca Canal, saving 360 acre-feet of water annually from evaporation and generating about 26 megawatts of power. The project, DeJong said, could make the Gila River Indian Irrigation and Drainage District the world’s first modern carbon-neutral irrigation project.

While the benefits of solar-shaded canals are clear in principle, some experts aren’t so sure the investment is worth the time and money. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation arrived at this conclusion in a 2016 analysis of the Central Arizona Project’s (CAP) 336-mile aqueduct.

The agency studied the feasibility of shading 975 feet of the canal with solar panels. They calculated this would cost $4.4 million while saving just 6 acre-feet of water annually—worth $1,020 at the time — and generating 1 megawatt of power. At this rate, covering the full length of the canal would save about 10,000 acre-feet of water from evaporation, enough to irrigate only one or two large farms.

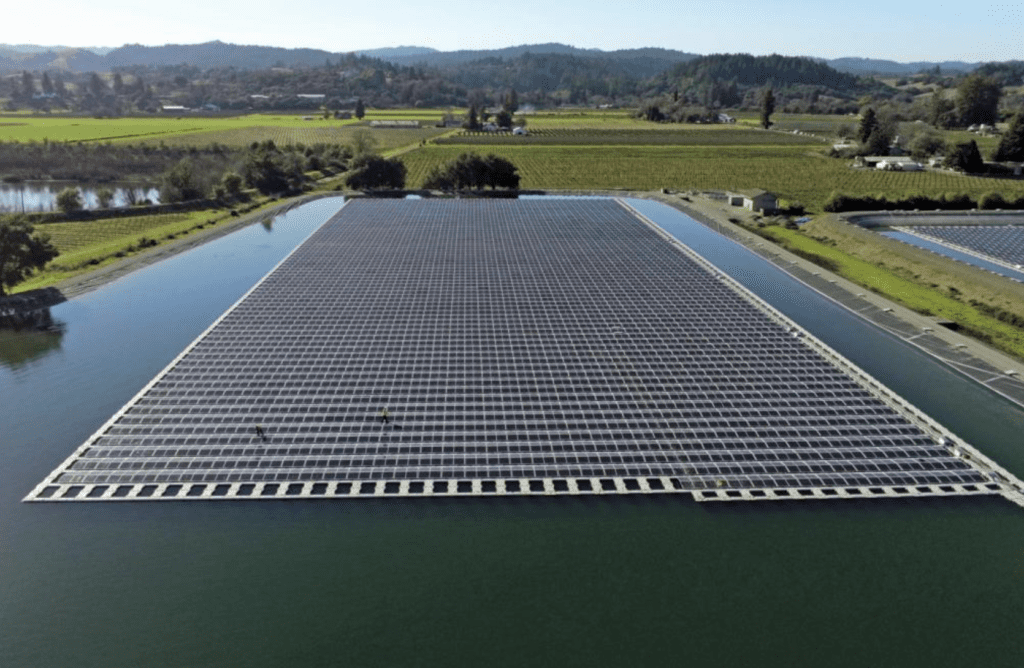

At larger scales, floating solar panels on reservoirs may save significantly more water than those over canals. At Arizona State University, civil engineerUpmanu Lall estimated that covering 10 percent of lakes Mead and Powell could cut evaporative loss by about 10 percent, saving 150,000 acre-feet a year and generating four times the electricity that the reservoirs’ hydropower plants currently produce.

Read the entire article at https://www.watereducation.org/western-water/solar-paneled-canopies-over-canals-catching-southwest

2. Water In Arizona: Photo Contest. Calling all photographers! The Water Resources Research Center (WRRC) is excited to announce its 2024 Photo Contest. This year, we are returning to the broader contest theme–Water in Arizona.

We invite you to showcase your talent by capturing anything from nature and wildlife to industry and agriculture, including people at play and work. It’s totally up to you—just make sure that all images somehow relate to water and are in Arizona. Categories include People/Pets, Nature/Wildlife, and The Built Environment. This year’s Special Category is “Borders.” We encourage you to use the theme of WRRC’s 2025 Annual Conference, Shared Borders, Shared Waters: Working Together in Times of Scarcity, to inspire your photographs. Photo submissions to the “Borders” category can be from any location. Winners will be announced at the 2025 Chocolate Fest in February (date TBD) and winning photographs will be featured on the WRRC website. Photo Contest images will be used in WRRC publications and other outreach materials. The deadline to submit photos is December 20, 2024. Additional information and contest eligibility/criteria can be found on our website. We look forward to seeing your amazing photos!

- Rules & Guidelines (https://wrrc.arizona.edu/wrrc-2024-photo-contest-rules-and-regulations)

- 2023 Contest Winners (https://wrrc.arizona.edu/opportunities/photo-contest/2023)

3. Written/Published Political Document Presents A Major Threat To The Environment. In just four years, the U.S. has made historic progress in the battle against climate change. And in a few short months, you and your community will determine the future of climate action.

That’s why you need to know about Project 2025. This dangerous agenda would eliminate essential protections for clean air and water, repeal clean energy investments and clear the path for Big Oil and other polluters to make money at your expense. But we have the power to stop it.

Project 2025 is an authoritarian playbook that would dismantle key climate and environmental safeguards on day one.

Project 2025 includes deeply concerning plans for our health and environment, including:

• Expanding the burning of dirty fossil fuels;

• Reversing essential protections for mankind: clean air, clean water and a livable climate;

• Decimating vital government agencies that protect public health, like the Environmental Protection Agency and the Food and Drug Administration;

• Rolling back the Inflation Reduction Act and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law; and

• Exiting the Paris agreement. (The Paris Agreement also called the Paris Accords or Paris Climate Accords) is an international treaty on climate change that was signed in 2016.[3] The treaty covers climate change mitigation, adaptation and finance.

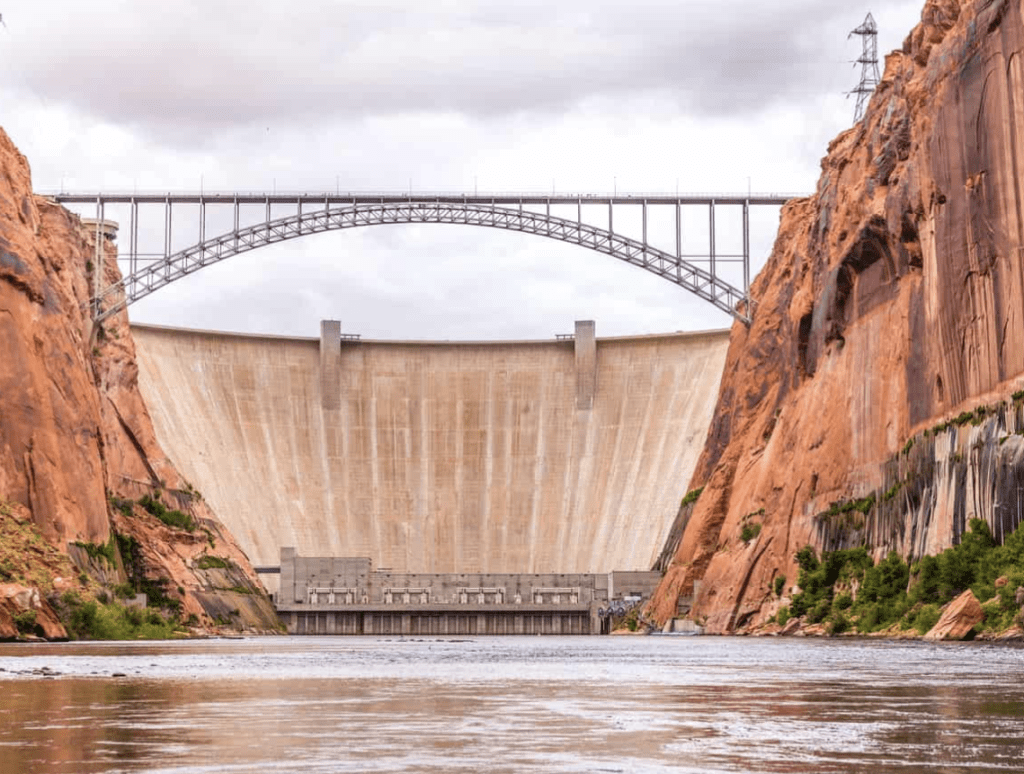

4. Glen Canyon Dam Producing 17% Less Electricity. What does that mean for Colorado Utilities? Fourteen of the lowest generation years at the dam have occurred since 2000, when the Colorado River Basin began experiencing a historic megadrought.

Glen Canyon Dam, which supplies electricity to 28 Colorado utilities, has been a stabilizing force in the West’s power supply. This year could be one of the lowest power production years ever.

Power generation at Glen Canyon fell by 17% on average from 2000 to 2023, compared with pre-drought years from 1988 to 1999, according to the Bureau of Reclamation, which manages the dam. The decline has made electric utilities more dependent on the volatile energy market, forced some to increasingly rely on fossil fuel energy sources, and raised rates by about 7%.

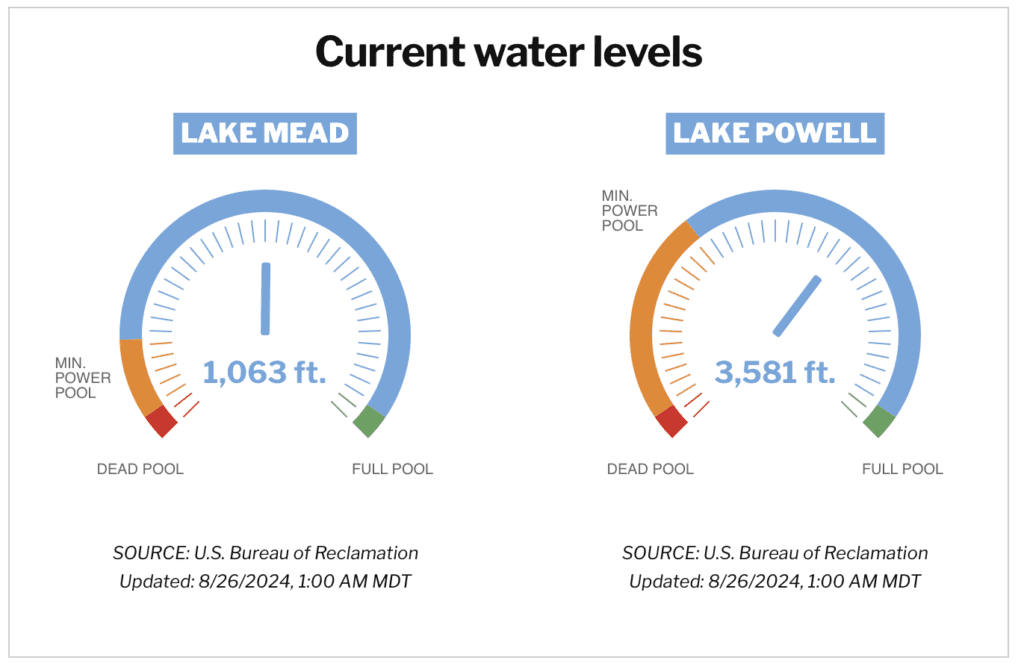

“Here in 2024, we’re expecting levels that are going to be among some of the lowest generation years that we’ve ever seen at Glen Canyon,” said Nick Williams with the Bureau of Reclamation. “Other than ‘22, you have to go back to the 1960s when the reservoir was still filling to find years as low as what we’ll see.”

Hydropower generation in 2024 is expected to be the second lowest year for generation with an estimated total of about 2.98 million megawatt-hours.

Near the Utah-Arizona border, Glen Canyon Dam catches Colorado River water that flows from Upper Basin states, including Colorado, New Mexico, Wyoming and Utah, in a massive reservoir called Lake Powell.

That water flows through turbines to generate hydroelectric power. Glen Canyon’s power is pooled with hydropower from other dams, including three in Colorado — Blue Mesa, Crystal and Morrow Point in Montrose and Gunnison counties — and delivered to Wyoming, Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Texas and Utah.

Glen Canyon makes up about 78% of the power produced by dams in the Colorado River Storage Project, which includes the dams in Gunnison and Montrose counties. If it can’t produce electricity, utilities would end up with less hydropower than expected.

The reservoir’s water levels have rebounded to about 3,581 feet — similar to water levels in 1969 and 2018 — since reaching an all-time low of about 3,521 feet in February 2023. Power generation, however, is slow to follow.

Lower water levels mean reduced annual releases from the dam, based on interstate rules established in 2007. Dam operators have to work within those annual limits as they try to balance the fluctuating demand for electricity with environmental regulations and operating restraints.

Lower water levels also make power generation less efficient because there is less pressure bearing down on the turbines. In 2023, Glen Canyon generated about 3,300 gigawatt-hours of electricity. If the reservoir had been full, it could have generated 4,390 gigawatt-hours, or 32% more energy.

5. OSHA Eight Hour Refresher Class. Need to update you OSHA Cert? A September class is coming in Glendale. $80 with continental breakfast and lunch. Contact dan (editor/instructor) at 623-930-8197 or [email protected].

Copyright 2024: EnviroInsight.org