Daniel Salzler No. 1261

EnviroInsight.org Three Items July 5, 2024

—————Feel Free To Pass This Along To Others——————

If your watershed is doing something you would like others to know about, or you know

of something others can benefit from, let me know and I will place it in this Information .

If you want to be removed from the distribution list, please let me know.

Please note that all meetings listed are open.

Enhance your viewing by downloading the pdf file to view photos, etc.

The attached is all about improving life in the watershed through knowledge.

If you want to be removed from the distribution list,

please let me know. Please note that all meetings listed are open.

Check our website at EnviroInsight.org

1.Colorado River Officials Propose Tracking Conserved Water. Upper Basin water managers exploring how to protect water in Lake Powell.

Water managers in the upper Colorado River basin took another step this week toward a more formal water conservation program that they say will benefit the Upper Basin states.

Representatives from Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico unanimously passed a motion Wednesday at a meeting of the Upper Colorado River Commission to explore creating a way to track, measure and store conserved water in Lake Powell and other upper basin reservoirs.

The motion directed staff and state advisers to prepare a proposal that lays out criteria for conservation projects and creates a mechanism for generating credit for those projects. The deadline for the proposal is Aug. 12, and commissioners plan to consider it at a late-summer meeting.

With an infusion of federal dollars from the Inflation Reduction Act, the Upper Colorado River Commission in 2023 rebooted the System Conservation Pilot Program, which pays water users — most of them in agriculture — to leave their fields dry for the season and let that water run downstream. Over two years, system conservation is projected to save about 101,000 acre-feet of water at a cost of about $45 million.

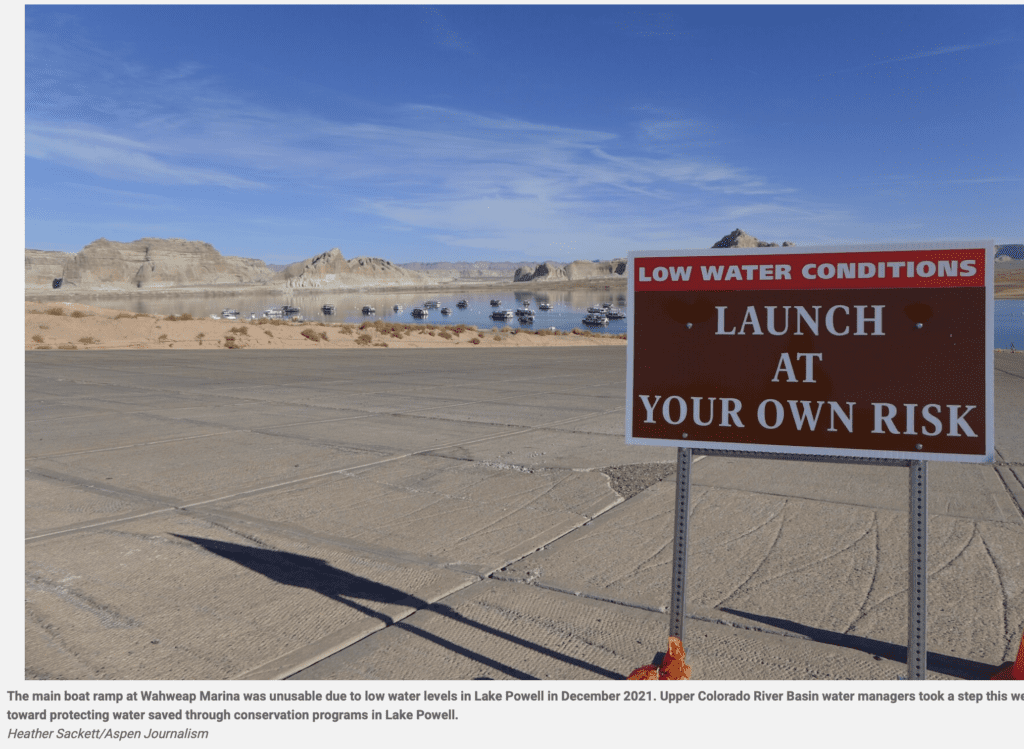

But how much of that water actually made it to Lake Powell is anyone’s guess. Despite one of the stated intentions of the program being to protect critical reservoir levels, the System Conservation Pilot Program has, so far, not tracked the conserved water, a process known as shepherding. The laws that govern water rights allow the next downstream users to simply take the water that an upstream user leaves in the river, potentially canceling out the attempt at conservation.

Some water managers and users have criticized the System Conservation Pilot Program for this lack of accounting, saying the water conserved by the upper basin is simply being sent downstream to be used by the lower basin. The Upper Colorado River Commission’s motion Wednesday for a proposal is an attempt to remedy that.

“We have heard from water users and others across the Upper Basin that there is interest in ‘getting credit’ for conserved water — in other words, protecting this water in Lake Powell,” Amy Ostdiek, the Colorado Water Conservation Board’s interstate, federal and water information section chief said in a prepared statement. “What the commissioners directed staff to do was simply to explore opportunities to do so.”

Tracking, measuring and storing the water saved by the upper basin states in Lake Powell is not a new idea. The concept was part of the 2019 Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan. The Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan created a special 500,000-acre-foot pool in Lake Powell for the Upper Basin to store water saved through a temporary, voluntary and compensated conservation program known as demand management.

Demand management is conceptually the same as system conservation, with the main difference being that system conservation water simply becomes part of the Colorado River system with no certainty about where it ends up, while demand management water would be shepherded, measured and stored in Lake Powell for the benefit of the Upper Basin.

“We can do things like the System Conservation Program, and if we set up an account such that we can put that conserved water into a pool, that can then accrue over time,” New Mexico Commissioner Estevan Lopez said at Wednesday’s meeting. “That can be a very useful tool when things get really dry in the system. Overall, we can make that water available to continue operations with additional stability.”

The goals of demand management were to help boost water levels in Lake Powell, allow for continued hydropower production at Glen Canyon Dam and, perhaps most important, help the upper basin states meet their obligations to deliver a minimum amount of water to the lower basin states under the terms of the 1922 Colorado River Compact. As climate change continues to rob rivers of flows, it becomes more likely that the Upper Basin won’t be able to deliver the 7.5 million acre-feet annually that is the Lower Basin’s share of the Colorado River, even if Upper Basin use doesn’t increase.

The conserved water “could be for compact compliance, or it could be for simply greater storage volume in the upper basin reservoirs to provide resilience against future dry years,” said Anne Castle, federal appointee and chair of the Upper Colorado River Commission. “It would be credited to the benefit of the upper basin, and that’s a little vague, but it’s because we haven’t designed that mechanism yet.”

In line with Upper Basin proposal

After two decades of drought, climate change and overuse, water levels in Lake Powell fell to their lowest point ever in 2022, threatening the ability to make hydropower at Glen Canyon Dam. Officials scrambled for solutions, with the Upper Colorado River Commission putting forth a “5-Point Plan,” one arm of which was restarting the System Conservation Pilot Program, which was originally tried from 2015-18.

Upper Basin officials have long maintained that the responsibility for a solution to the Colorado River crisis rests with the lower basin states: California, Arizona and Nevada. And they are still reluctant to say that Wednesday’s motion is a move toward a long-term conservation program for the upper basin.

“I wouldn’t say that we’re on the cusp of a permanent program, but rather that this is an evolving overall conservation effort that is incorporating what we’ve learned from the previous iterations,” Castle said.

Wednesday’s motion was also the beginning of making good on a promise laid out in the Upper Basin’s alternative proposal for how the river and reservoirs should be operated in the future. The proposal says the four states will pursue “parallel activities” that include voluntary, temporary and compensated reductions in use, such as conservation programs that store water in Lake Powell.

2. Yavapai-Apache Nation Reaches Water Settlement After Change In State Policy. Another tribe in Arizona has secured its water supply, this time after a 50-year-long struggle.

The Yavapai-Apache Nation approved its water rights settlement June 26, which will bring new water supplies to the Verde Valley and settle the tribe’s decades-long water rights claims. The settlement is the latest after Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs reversed a state policy that complicated tribes’ efforts to claim their rights to water.

Yavapai-Apache Chairwoman Tanya Lewis said the agreement, which was negotiated with local communities, the Salt River Project, and state and federal officials will bring real “wet” water to her tribe.

At the center of the settlement: constructing a pipeline from the C.C. Cragin Reservoir on the Mogollon Rim along Forest Service roads to the Verde Valley. SRP manages the reservoir and the water it holds.

In the deal, the pipeline will deliver dedicated sources of water from the Cragin Reservoir to the Yavapai-Apache Nation. It will also allow the tribe to exchange 1,200 acre-feet of its Central Arizona Project water with SRP for an additional delivery of water from C.C. Cragin in the same amount.

The settlement will also confirm the Yavapai-Apache Nation’s historic irrigation rights as well as certain rights to pump groundwater, including when C.C. Cragin Reservoir levels are low. The tribe also has the right to acquire future water rights under the settlement.

The Yavapai-Apache Nation will also waive, among other things, claims for damages to water rights against existing water users in the Verde River watershed and against the United States.

“We congratulate the Yavapai-Apache Nation on approving the nation’s settlement and look forward to recommending it to the SRP Board for approval in the near future,” says Leslie Meyers, SRP’s associate general manager who also heads water resources and services.

She said the settlement would bring water certainty to the community and facilitate renewable water supplies and cooperative water stewardship in the Verde Valley.

The 2,700-member tribe will also be able to sustainably reuse effluent water thanks to an upcoming wastewater treatment facility funded by a loan from the Water Infrastructure Finance Authority of Arizona. The $16.3 million loan, of which $1.65 million is forgivable, will fund replacing an outdated sewage lagoon system that serves 176 customers, including the Cliff Castle Casino and Hotel, the Yavapai-Apache Nation Cultural Center and tribal homes after the project is completed in 2026.

The new plant will enable the tribe to use high-quality reclaimed water in its farming operations, which will reduce groundwater pumping to help protect Verde River flows.

The tribe said preserving the river also helps preserve cultural resources, maintain the character of the valley and drive tourism and economic development in the region.

A secure water supply also means that the tribe can continue to rebuild its land base, lost when its original reservation was closed and handed off to new settlers.

Source: Debra Utacia Krol, Arizona Republic

3. Arroyo 2024 :Solutions To Arizona’s WaterChallenges: What CanWe Do? Water resources in Arizona are under stress from climate change, a two-decade megadrought, and chronic overuse. These combined influences have led to surface water losses, drying streams and wetlands, and groundwater depletion as pumping exceeds replenishment. Communities are facing the possibility that the water sources they rely on now may shrink in the future, or even vanish. Uncertainty regarding Colorado River water — a large component of Arizona’s water portfolio and one that is shared with six other US basin states — also raises questions about Arizona’s water future. The quality of available water is a concern as well. Where supply is limited, lower quality water and wastewater can be valuable resources, but only if they can be treated to suitable standards. These concerns beg the question: What can be done?

That very question was the focus of the Water Resources Research Center’s 2023 annual conference, “What Can We Do? Solutions to Arizona’s Water Challenges.” Panelists and presenters highlighted ongoing efforts to address the state’s water challenges, as well as new and innovative solutions currently under development. During the conference, several additional themes emerged, such as the need for better, more accessible data, improved technology, and collaboration. Read more at https://wrrc.arizona.edu/sites/wrrc.arizona.edu/files/2024-06/Arroyo-2024.pdf

Source: University of Arizona Water Resources Research Center

Copyright: 2024 EnviroInsight.org