Daniel Salzler No. 1236 EnviroInsight.org Two Items January 12, 2023

—————Feel Free To Pass This Along To Others——————

If your watershed is doing something you would like others to know about, or you know

of something others can benefit from, let me know and I will place it in this Information .

If you want to be removed from the distribution list, please let me know.

Please note that all meetings listed are open.

Enhance your viewing by downloading the pdf file to view photos, etc.

The attached is all about improving life in the watershed through knowledge.

If you want to be removed from the distribution list,

please let me know. Please note that all meetings listed are open.

Check our website at EnviroInsight.org

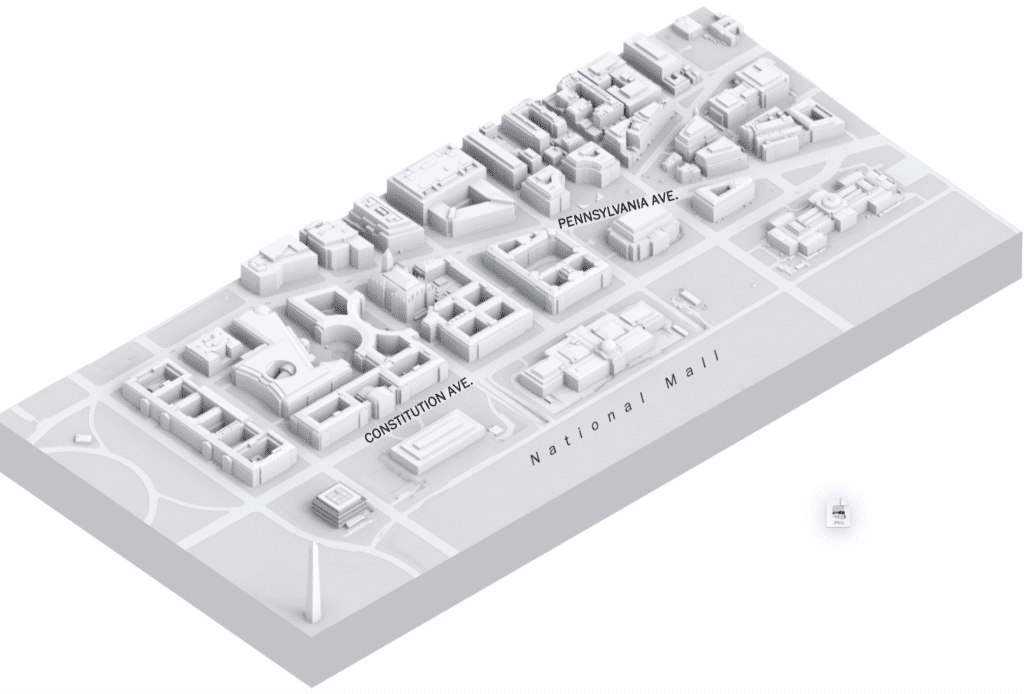

1. A National View Of Our Capital, Built On Water, Struggling To Keep From Drowning.

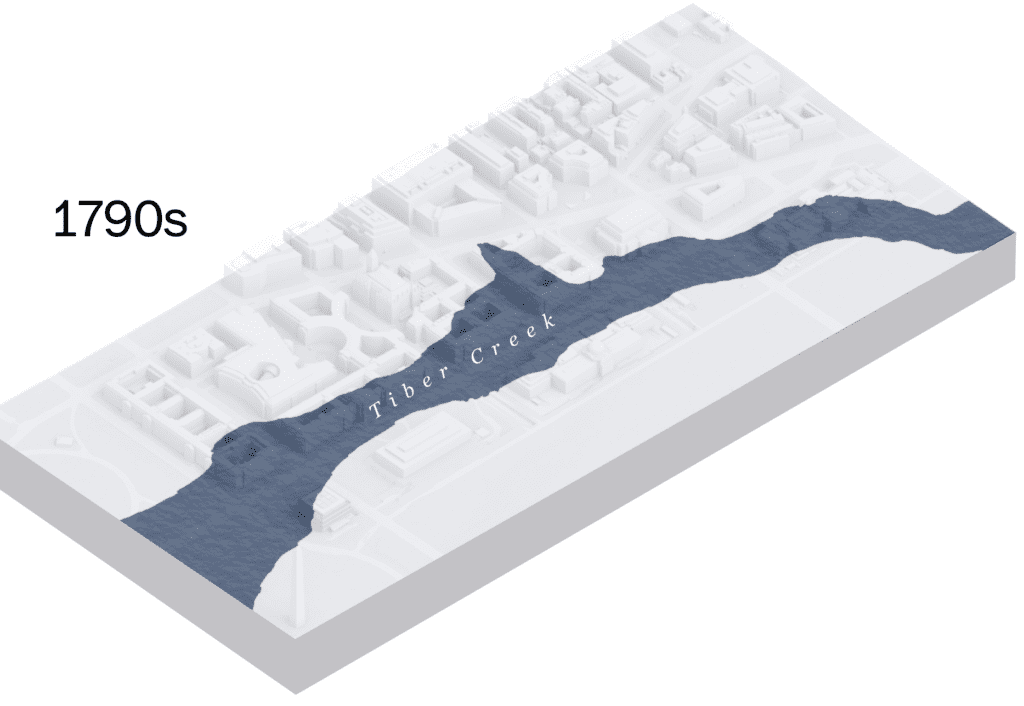

This is the shoreline George Washington would have seen in 1791, when he chose the site for the nation’s new capital.It was a land of wetlands, marshes and creeks.

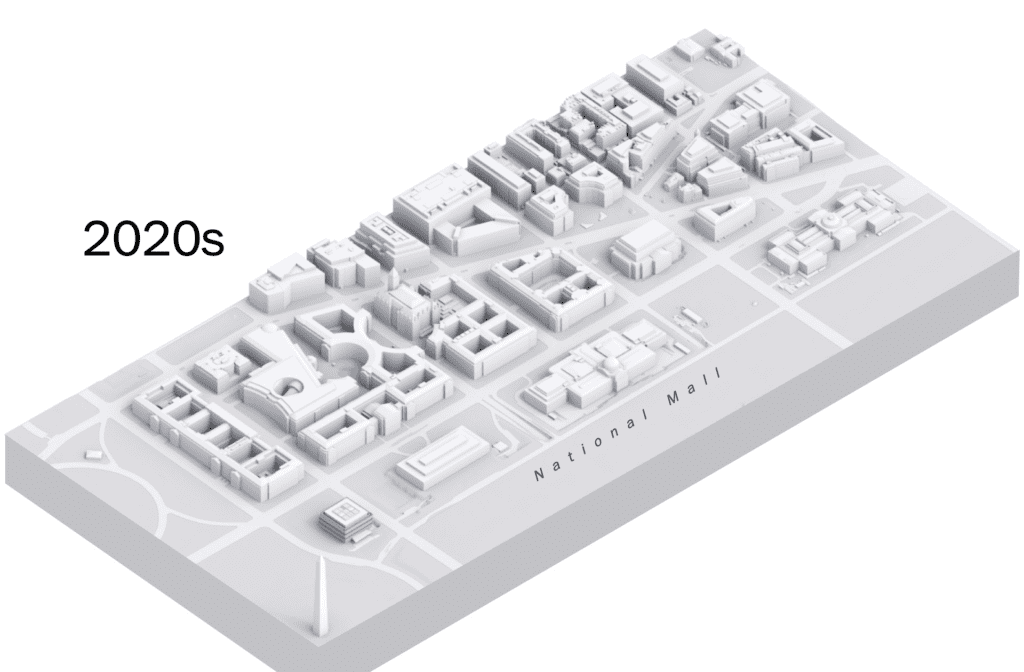

Horse-drawn carts carried crushed rock from the construction site of the Capitol, nearby quarries and sediment dredged from the Potomac River. The fill was compacted to create the land where the National Mall sits today.

Wet boards on the bottom right show where excavators hit water from the burried Tiber Creek while digging the basement for the African American museum in 2012. Washington Post

The African American museum was built on the lowest and last spot then available on the Mall. Engineers had expected to hit water, but the forces of nature they disturbed put the project in immediate peril.

Derek Ross, head of museum construction, despaired as he stared into the colossal 80-foot pit where workers were digging out the basement for the new African American history museum. The huge excavators had broken into a hard clay soil that encased much of Tiber Creek, which was buried 150 years ago. Over the decades, the soil had formed a pressurized cushion around the underground aquifer that held up other buildings on the Mall. But now, it seemed in danger of collapsing.

The water was rushing out of the aquifer more quickly than it was being replenished by the creek. It was the same aquifer that flowed under the Washington Monument, a mere 800 feet away. Ross worried that if the cushion collapsed, the monument would shift or, worse, topple over. When he closed his eyes, he saw a giant sinkhole.

“I had a recurring dream that I’d walk to work one day and the Washington Monument wouldn’t be there.”

The work had to stop. Water pumps around the monument normally used to pull extra water out of the ground during rainstorms were reconfigured to force water back underground to refill the cushion. Piezometers were installed to measure the pressure and level of groundwater.

What excavators unearthed at the site of the African American museum in 2012 was not only the long-forgotten topography of the nation’s capital, but a subterranean geology that, two centuries later, determines the city’s vulnerability to catastrophic flooding as climate change intensifies storms, rainfall and sea-level rise.

The buildings that make up the Federal Triangle sit on land reclaimed from Tiber Creek. Once a few hundred feet wide, the creek ran along what is now Constitution Avenue, and drained much of Washington into the Potomac.

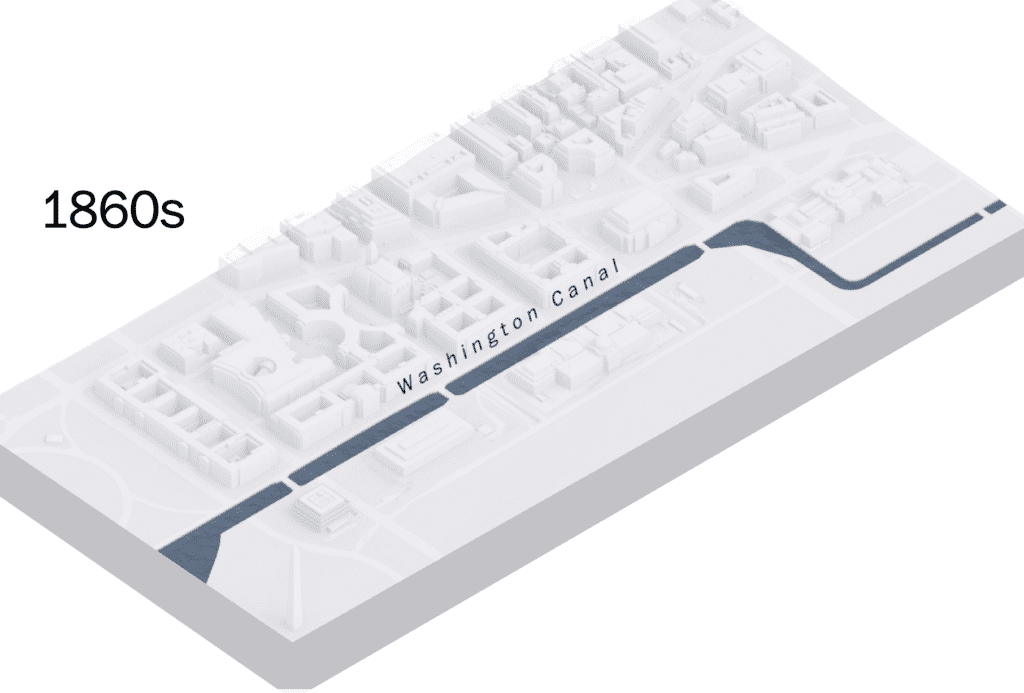

The plan for the new capital turned Tiber Creek into a canal. But that attempt to harness nature backfired because the waterway was often choked with sediment, pollution and sewage.

At risk are the national treasures housed inside the Federal Triangle,the low-lying area between the White House and the Capitol, home to 39 critical government facilities, $14 billion in property and irreplaceable artifacts of America’s history.

Personal treasures and the homesand businesses of Washingtonians living atop historical, buried streams across the city, are regularly inundated with raw sewage and filthy water. Urban floods can be fatal, as in August when 10 dogs drowned inside a kennel on Rhode Island Avenue NE, a location with a decades-old flood history.

While federal Washington is best known for its neoclassical buildings and white marble monuments, the District of Columbia is actually a low-lying delta city like New Orleans, but one constructed on top of settling rock and rubble fill.

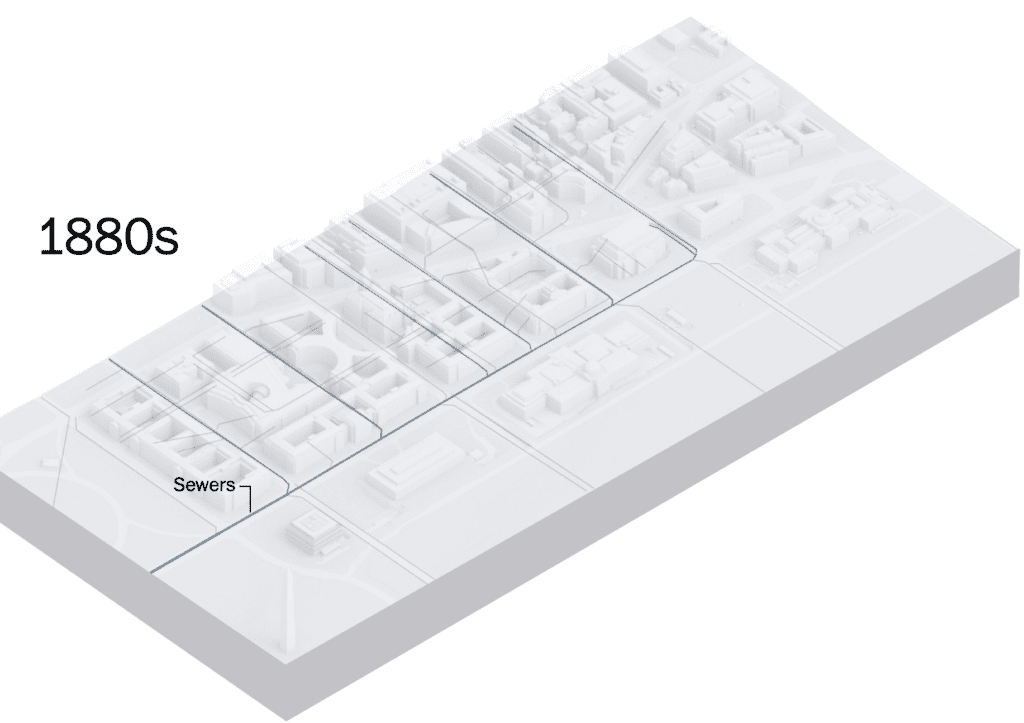

Buried but not vanished, the underground streams and canals became part of a permanent high-water table in the downtown area known decades later as the Federal Triangle.

To improve sanitation, the city covered Tiber Creek and created a sewer.The plan for the new capital turned Tiber Creek into a canal. But that attempt to harness nature backfired because the waterway was often choked with sediment, pollution and sewage.

Then there’s the water that comes from the gigantic Potomac Watershed, where the rain falling on the 14,690 square-mile region travels from as far away as the Appalachian Mountains in West Virginia, down the streams of the Piedmont’s hard rock, past the Atlantic Fall Line onto the sandy Atlantic Coastal Plain. From there, it flows into the Potomac River and then Chesapeake Bay on its way to the wide-open Atlantic Ocean.

The Lincoln Memorial, pictured here first in 1917, was built on drained land that would become the National Mall. The photo to the right is the same view on June 30, 2023 from the World War II Memorial (National Photo Company Collection, Library of Congress)

Before colonization, when Native American tribes lived here, rainfall was naturally absorbed along its journey to the ocean by marshes and streams. Once European settlers began clearing and grading the land for farming, though, the ground became less permeable. Erosion and runoff carried massive quantities of sediment downstream and deposited them into mud flats along the banks of the Potomac.

A few centuries later, the Army Corps of Engineers reshaped them into the Reflecting Pool, Tidal Basin and adjoining parkland.

Fast forward to the 21st century, a heavy downfall on top of a high-water table in an already low-lying area such as the Federal Triangle can even “cause the water to come back up from the ground,” said Karen Prestegaard, a geologist at the University of Maryland. A series of spectacular floods has resulted.

The result was the first museum on the National Mall to listen to what nature is telling us about coexisting on the planet in the era of climate change.Builders hauled in loads of fill to lift the building’s ground level 15 feet above the rest of the Mall.

To protect the five stories underground, the African American museum’s basement has double walls eight feet apart from each other. The inner wall is coated with a waterproof skin. Between the two walls, gravel and light concrete absorb any water that might seep in. The two walls are capped with another waterproof barrier. The lawn surrounding the museum’s above-ground bronze crown is actually a grass roof installed to absorb rainwater.

Two buried tanks, one that holds 100,000 gallons,the other 15,000 gallons, capture rain and underground water that collects near the basement and uses it to flush toilets and water the landscaping. In a flood, the full cisterns can wait to release their loads

A state-of-the-art flood wall protects the museum’s “Achilles’ heel,” as Ross calls the entrance to the underground loading dock, the lowest part of the building. “It doesn’t require any human beings,” he said, because people make mistakes. Instead, the flood wall is automatically triggered when a flotation device underneath it senses the presence of water.

Other Smithsonian museums in or near the 100-year flood plain are being slowly retrofitted with flood protection: A new flood gate is up at the National Air and Space Museum; the chronically flooded Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden is getting its first storm water system; and the National Museum of American History, the most vulnerable of the Smithsonian museums, will get two cisterns and higher flood gates, and send its basement-level collection to Suitland, Md. for storage.

Under the worst-case climate scenario, the American History museum could find itself beyond protection of the 17th St. Levee and “under 16.3 feet of water,” according to the Army Corps and the D.C. Climate Projections & Scenario Development Report. Source: Washington Post

2. A Smithsonian Study Reveals That Reindeer Sleep and Eat Simultaneously. This allows them to save energy in the short Artic Summer. While the animals chew their cud, they also enter a state of rest. Source: Smithsonian magazine December 22, 2023

Copyright 2023 EniroInight.org