+

Daniel Salzler No. 1199

EnviroInsight.org Two Items April 28, 2023

—————Feel Free To Pass This Along To Others——————

If your watershed is doing something you would like others to know about, or you know

of something others can benefit from, let me know and I will place it in this Information .

If you want to be removed from the distribution list, please let me know.

Please note that all meetings listed are open.

Enhance your viewing by downloading the pdf file to view photos, etc.

The attached is all about improving life in the watershed.

If you want to be removed from the distribution list,

please let me know. Please note that all meetings listed are open.

Check our website at EnviroInsight.org

- WOTUS Now Official. Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972, Public Law 92–500, 86 Stat. 816, as amended, 33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq. (Clean Water Act or Act) ‘‘to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation’s waters.’’ 33 U.S.C. 1251(a). Waters Of The United States .

In doing so, Congress performed a ‘‘total restructuring’’ and ‘‘complete rewriting’’ of the

then-existing statutory framework, designed to ‘‘establish an all-encompassing program of

water pollution regulation.’’. Congress thus intended the 1972 Act to be a bold step forward

in providing protections for the nation’s waters. Central to the framework and protections

provided by the Clean Water Act is the term ‘‘navigable waters,’’ defined broadly in the Act

as ‘‘the waters of the United States, including the territorial seas.’’

This term is relevant to the scope of most Federal programs to protect water quality under the

Clean Water Act—for example, water quality standards, permitting to address discharges of

pollutants, including discharges of dredged or fill material, processes to address impaired

waters, oil spill prevention, preparedness and response programs, and Tribal and State water

quality certification programs—because the Clean Water Act uses the term ‘‘navigable

waters’’ in establishing such programs. As a unanimous Supreme Court concluded decades

ago, Congress delegated a ‘‘breadth of federal regulatory authority’’ in the Clean Water Act

and expected the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Department of the Army

to tackle the ‘‘inherent difficulties of defining precise bounds to regulable waters.’’

The Court went on to state that protection of aquatic ecosystems, Congress recognized,

demanded broad federal authority to control pollution, for water moves in hydrologic cycles

and it is essential that discharge of pollutants be controlled at the source

After more than 45 years of implementing the longstanding pre-2015 regulations defining

‘‘waters of the United States.’’ The agencies’ experience includes more than a decade of

implementing those regulations consistent with the Supreme Court’s decisions. The agencies

also considered the extensive public comments on the proposed rule. This rule establishes

limits that appropriately draw the boundary of waters subject to Federal protection.

When upstream waters significantly affect the integrity of waters for which the Federal

interest is indisputable—the traditional navigable waters, the territorial seas, and interstate

waters— this rule ensures that Clean Water Act programs apply to protect those paragraph

waters by including such upstream waters within the scope of the ‘‘waters of the United

States.’’

Where waters do not significantly affect the integrity of waters for which the Federal interest

is indisputable, this rule leaves regulation exclusively to the Tribes and States. Additionally, it

is important to note that the fact that a water is one of the ‘‘waters of the United States’’ does

not mean that no activity can occur in that water; rather, it means that activities must comply

with the Clean Water Act’s permitting programs, and those programs include numerous

statutory exemptions and regulatory exclusions.

Waters of the United States’’ includes:

- traditional navigable waters, the territorial seas, and interstate waters;

- impoundments of ‘‘waters of the United States’’ impoundments’’);

- tributaries to traditional navigable waters, the territorial seas, interstate waters, impoundments when the tributaries meet either the relatively permanent standard or the significant nexus standard (‘‘jurisdictional tributaries’’)

- wetlands adjacent to waters, wetlands adjacent to and with a continuous surface connection to relatively permanent impoundments, wetlands adjacent to tributaries that meet the relatively permanent standard, and wetlands adjacent to impoundments or jurisdictional tributaries when the wetlands meet the significant nexus standard (‘‘jurisdictional adjacent wetlands’’); and intrastate lakes and ponds, streams, or wetlands not identified in paragraphs (a)(1) through (4) that meet either the relatively permanent standard or the significant nexus standard. The ‘‘relatively permanent standard’’ refers to the test to identify relatively permanent, standing or continuously flowing waters connected to waters, and waters with a continuous surface connection to such relatively permanent waters or to traditional navigable waters, the territorial seas, or interstate waters.

The ‘‘significant nexus standard’’ refers to the test to identify waters that, either alone or in combination with similarly situated waters in the region, significantly affect the chemical, physical, or biological integrity of traditional navigable waters, the territorial seas, or interstate waters. The regulatory text defines ‘‘significantly affect’’ in order to increase the clarity and consistency of implementation of the significant nexus standard. With respect to ‘‘adjacent wetlands,’’ the concept of adjacency and the significant nexus standard create separate, additive limitations that work together to ensure that such wetlands are covered (i.e., jurisdictional under the Act) when they have the necessary relationship to other covered waters. The adjacency limitation focuses on the relationship between the wetland and the covered water to which it is adjacent. Consistent with the plain meaning of the term and the agencies’ 45-year-old definition of ‘‘adjacent,’’ the rule requires that an ‘‘adjacent wetland’’ be ‘‘bordering, contiguous, or neighboring’’ to another covered water.

Where a wetland is adjacent to a traditional navigable water, the territorial seas, or an interstate water, consistent with longstanding regulations and practice, no further inquiry is required, and the wetland is jurisdictional. But where a wetland is adjacent to a covered water that is not a traditional navigable water, the territorial seas, or an interstate water, such as a tributary, this rule requires an additional showing for that adjacent wetland to be covered: the wetland must satisfy either the relatively permanent standard or the significant nexus standard. And that inquiry, under either standard, fundamentally concerns the adjacent wetland’s relationship to the relevant paragraph (a)(1) water rather than the relationship between the adjacent wetland and the covered water to which it is adjacent. In other words, the adjacent wetland must have a continuous surface connection to a relatively permanent, standing or continuously flowing water connected to a water, or must either alone or in combination with similarly situated waters significantly affect the chemical, physical, or biological integrity of a paragraph (a)(1) water.

The agencies find that the scope of Clean Water Act jurisdiction established in this final rule enhances States’ ability to protect waters within their borders, such as by participating in the section 401 certification process and by providing input during the permitting process for out-of-state section 402 and 404 permits that may affect their waters.

This rule establishing the definition of ‘‘waters of the United States’’ does not by itself impose costs or benefits. Potential costs and benefits would only be incurred as a result of actions taken under existing Clean Water Act programs relying on the definition of ‘‘waters of the United States’’ (i.e., sections 303, 311, 401, 402, and 404).

For convenience, the agencies in this preamble will generally cite the Corps’ longstanding regulations and will refer to ‘‘the 1986 regulations’’ as including EPA’s comparable regulations and the 1993 addition of the exclusion for prior converted cropland. The 1986 regulations define ‘‘waters of the United States’’ as follows (33 CFR 328.3 (2014)): 31 (a)

The term ‘‘waters of the United States’’ means:

1. All waters which are currently used, were used in the past, or may be susceptible to use

in interstate or foreign commerce, including all waters which are subject to the ebb and

flow of the tide;

2. All interstate waters including interstate wetlands;

3. All other waters such as intrastate lakes, rivers, streams (including intermittent

streams), mudflats, sandflats, wetlands, sloughs, prairie potholes, wet meadows, playa

lakes, or natural ponds, the use, degradation, or destruction of which would or could

affect interstate or foreign commerce including any such waters: i. Which are or could

be used by interstate or foreign travelers for recreational or other purposes; or ii. From

which fish or shellfish are or could be taken and sold in interstate or foreign commerce;

or iii. Which are used or could be used for industrial purposes by industries in

interstate commerce;

4. All impoundments of waters otherwise defined as waters of the United States under this definition;

5. Tributaries of waters identified in paragraphs (a)(1) through (4) of this section;

6. The territorial seas; and

7. Wetlands adjacent to waters (other than waters that are themselves wetlands) identified in paragraphs (a)(1) through (6) of this section.

8. Waters of the United States do not include prior converted cropland. Notwithstanding the determination of an area’s status as prior converted cropland by any other Federal agency, for the purposes of the Clean Water Act, the final authority regarding Clean Water Act jurisdiction remains with EPA. Waste treatment systems, including treatment ponds or lagoons designed to meet the requirements of Clean Water Act (other than ` cooling ponds as defined in 40 CFR 423.11(m) which also meet the criteria of this definition) are not waters of the United States.

|2.Summer Heat and More: An All-Hazard Approach to Working Outdoors.Employers and employees need to watch out for more than just hot weather during the summer. By Karen D. HamelMar 01, 2023 OS&H magazine.

After the ice and snow begin to melt, but before the daffodils start blooming and the faint murmurs of folks yearning for warm summer weather usually start. For some, it means vacations, relaxation and time with family. For many employees, however, it means working in high heat and humidity.

With OSHA and several industry groups engaged in rulemaking and the creation of consensus standards to help protect both indoor and outdoor workers who still need to work regardless of the heat, it can be easy to focus solely on creating plans to help prevent dehydration and heat-related injuries. But summer brings other risks that may need to be addressed as well.

Recognizing all of the hazards that summer work presents and including them in planning efforts help to reduce risk. It will also help with training and emergency response efforts.

Currently, federal OSHA does not require employers to create a written plan that addresses how workers will be protected from summer hazards. However, employers do have a responsibility to evaluate workplace hazards—including all types of hazards that come from working outdoors and in summer weather.

Some locations may have similar hazards while others have scenarios that are unique to the facility. Some risks may be specific to the day and time that work is being performed. Involving employees in the planning process is a proven way to help ensure that all known summer hazards are addressed.

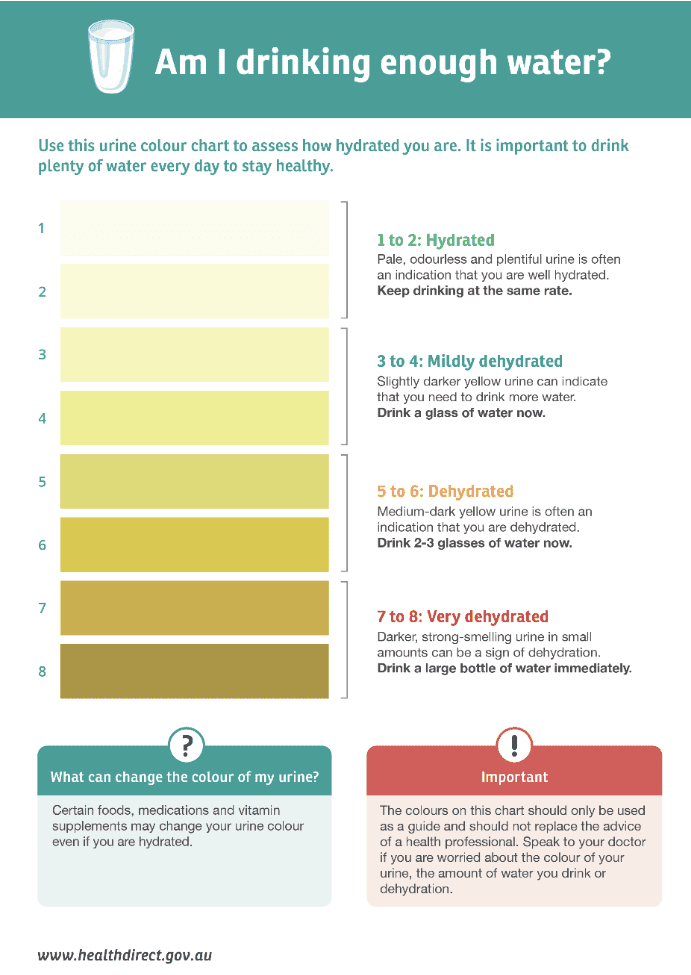

Heat and Humidity

While some summer hazards may come and go, heat and humidity are likely to be daily issues that typically can’t be engineered out of the process. Recognizing heat and humidity as hazards and planning for them is important because each year, an average of 32 employees die from heat-related injuries, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Many of these fatalities are

new or temporary workers who have not been properly acclimated to working in hot and humid conditions. Written plans that address work schedules, buddy systems, hydration breaks and supervisors’ duties during hot weather work protect not only these employees but also the more seasoned ones.

Although a federal rule has not been finalized, guidance is available from the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) and other industry groups. This guidance can help facilities establish appropriate work/rest cycles based on the temperature, humidity and the types of protective clothing employees are wearing. There is even an app that can be downloaded to any smart device to let employers, supervisors and employees åÅ the heat index in any area of the U.S.

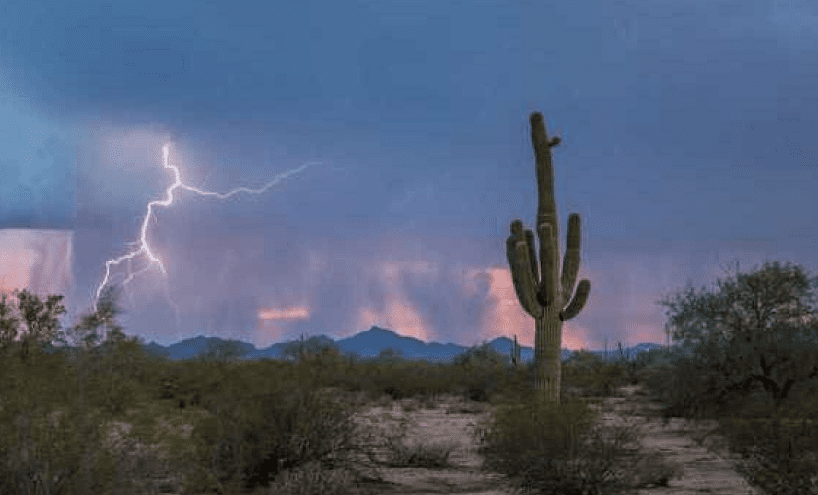

Storms and Flooding

A nice, steady rain usually helps to reduce the temperature a bit. However, working during a storm presents a different set of challenges. For example, employees working in open spaces, on tall buildings or near anything that conducts electricity need to be aware of the potential for lightning strikes and know how to get to a designated safe place to reduce their risk of being struck.

Even if lightning isn’t a threat, summer storms bring rain that can make working surfaces slippery. Employees working at heights are especially vulnerable, but even those at ground level can still be at risk for slips and falls on smooth or muddy surfaces.

Sometimes, a storm is more than just rain. Summer traditionally sees the winding down of tornado season just as hurricane season begins to ramp up. In areas where tornadoes or hurricanes are known to happen, be sure to include training on how to prepare and respond to these emergencies.

Employees who may be involved in recovery efforts after storms or flooding face additional risks. In fact, OSHA, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) have all issued guidance documents for workers who are involved in flood cleanup.

Vermin and Animals

Humans aren’t the only creatures that relish a daily dose of Vitamin A from the sun. Many insects and animals also enjoy basking in the sun’s rays.

Mosquitoes, ants and bees are the most common insects that employees face. In some areas, other insects like fire ants, beetles or dragonflies appear in the daily mix. In addition to controls such as emptying anything that has standing water and keeping lawns mowed, providing employees with long-sleeved shirts, long pants, boots and insect repellant helps to minimize exposure.

Perhaps more annoying than insects are arachnids including ticks, spiders and scorpions. While ticks actively seek human (and animal) hosts, spiders and scorpions generally try to get away from people. Train employees to recognize biting, poisonous and venomous insects, what actions they can take to avoid being bitten as well as first aid measures.

Snakes and wild animals vary from region to region but can also be a significant threat to employees. State agencies often have training programs that they can provide at no cost to help employees recognize and avoid injuries from harmful animals in their region.

Poisonous Plants

On the first day of summer camps, countless children across the U.S. are taught “leaflets of three, let them be” as a way to help them recognize and avoid poisonous plants in wooded areas. It’s good advice for adults as well.

Because poison ivy, oak and sumac don’t only lurk in the forest, it helps to be able to recognize them and know which varieties may be present in different work areas. Wearing disposable PPE or long sleeves, long pants, boots and gloves can help prevent the urushiol oil in the leaves of these plants from coming in contact with skin. Barrier creams can also help reduce the risk.

About 15 percent of Americans are not allergic to poison ivy, oak or sumac, according to the American Skin Association. For the remaining 85 percent of the population, contact with the leaves of these plants can cause swelling, redness, itching and other allergic reactions.

Include cleanup procedures during poisonous plant training. Urushiol can remain on surfaces for up to five years if it is not physically removed. Exposed clothing can be washed separately with detergent and hot water. Tools and equipment can be cleaned with alcohol or with soap and lots of water.

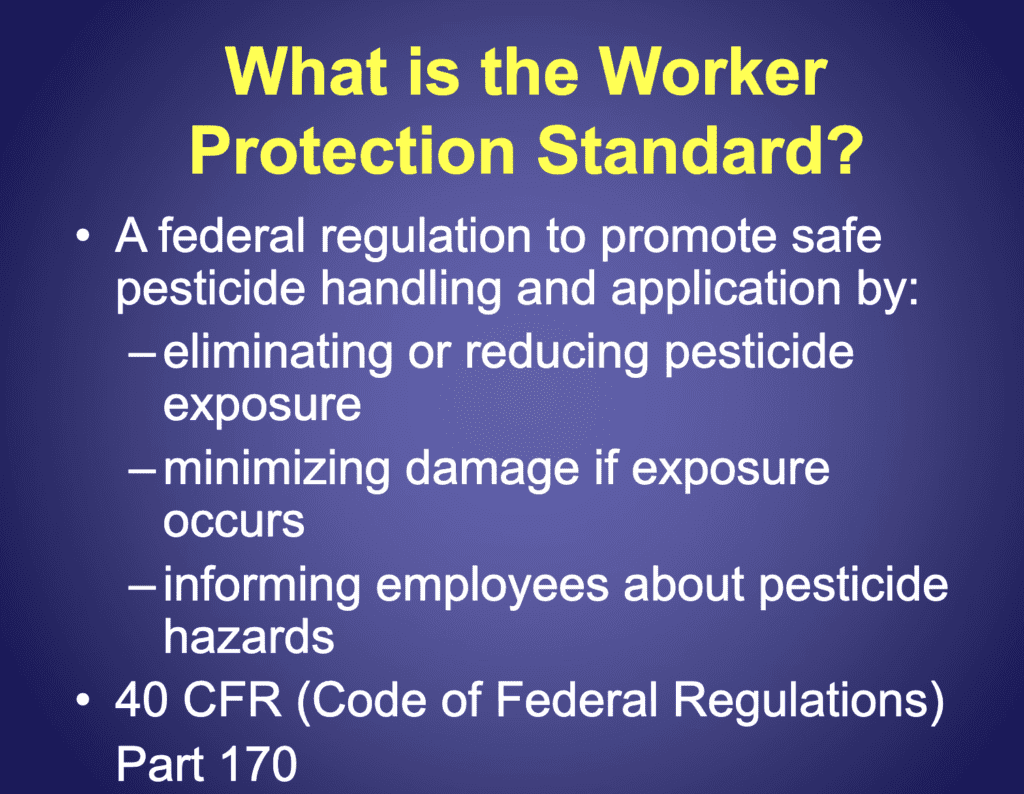

Pesticides

Employees who handle pesticides that are being applied to agricultural crops are governed under the EPA’s Worker Protection Standard (40 CFR 170). This body of regulations outlines the training requirement as well as other protections for workers involved in these operations.

While the EPA has jurisdiction over much that has to do with the manufacturing, distribution, application and use of pesticides, that doesn’t mean that it isn’t a safety issue. It is still important to evaluate the safety data sheets and labels of any pesticides being used so that preparations can be made for employees to apply and work around them safely.

Summer Vacationing

When summer finally comes, it can be tempting to relax and

be grateful that the harshness of winter is gone—at least for a season. Creating and maintaining a comprehensive safety plan that encompasses all of the hazards that employees may face when working outdoors in the summer is key to providing that respite. Training employees and providing them with the procedures, tools and provisions they’ll need to not only beat the heat but also tackle everything else that summer throws their way will help them to have a safer summer, too.

Copyright EnviroInsight.org 2023