Daniel Salzler No.1088

EnviroInsight.Org. Six Items January 29, 2021

Feel Free To Pass This Along To Others

If your watershed is doing something you would like others to know about, or you know of something others can benefit from, let me know and I will place it in this Information newsletter.

If you want to be removed from the distribution list, please let me know.

Please note that all meetings listed are open.

The attached is all about improving life in the watershed.

1. Beyond Bees, Neonics Damage Ecosystem—and a Push for Policy Change Is Coming.

Scientists point to the long-term negative impacts of nicotinoids, and advocates hope a regulatory overhaul will help.

Last June, a national partnership that tracks honey bee population declines released the results of its annual survey. Between April 2019 and April 2020, beekeepers reported losing nearly 44 percent of their colonies, the second highest rate since the first survey in 2010.

For people paying attention to the many studies that have been piling up over the last decade documenting the devastating effects of neonicotinoids on the powerful pollinators, the news was far from surprising.

Neonicotinoids—or neonics—are now the most widely used insecticides in the world, and nearly all conventional corn and soy farmers in the U.S. plant seeds coated with the chemicals. As the evidence that neonics kill pollinators by attacking their nerve cells has grown stronger (with industry-funded studies also confirming harm), multiple publications have warned of an “insect apocalypse.” timated between 80 and 100 percen So far, the U.S. has not followed suit. In early 2020, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) filed an interim decision to allow the continued use of the five most popular neonics, with minimal restrictions.

At the same time, some environmental groups and lawmakers have sharpened their criticism, drawing attention to the issue with new intensity through lawsuits and legislative campaigns. Two different bills that would restrict neonic use were introduced at the federal level in 2020. At least one, the Protect America’s Children from Toxic Pesticides Act (PACTPA), will be reintroduced to a new Congress this year and also includes what advocates say are meaningful updates to EPA pesticide approval processes.

Meanwhile, several state-level efforts are picking up steam in New York, California, and elsewhere.

Scientists and advocates say regulation can’t happen soon enough, given the recent body of research that points to harms that extend far beyond pollinators to widespread soil and water contamination affecting aquatic animals, birds, mammals, and entire ecosystems.

Daniel Raichel, a staff attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), said that when he first started working on neon regulation in the summer of 2016, he thought colleagues who referred to the issue as a “second Silent Spring” were exaggerating. “I don’t believe that anymore,” he said. “We’re getting a new study every couple of weeks, and the scale and scope of the ecological problems that we are seeing is off the charts. It’s a bee issue for sure, but really, it’s an ecosystem issue. It’s an everything issue.”

At the same time, there is new evidence that the most widespread use of the insecticides—as treated corn and soy seeds—does not lead to yield or income increases for farmers, evidence that runs contrary to industry claims. Still, the same study found some fruit and vegetable farmers do depend on the chemicals, and most farm groups oppose banning neonics on the basis that it could impact their production.

“I think the lack of options for some farmers is pretty striking,” said Mike Stranz, the vice president of advocacy at the National Farmers Union (NFU). “We can’t deny the seriousness of the situation that comes with impacts on pollinators, but there are also some serious implications for farmers. That’s the balance that needs to be struck here.” The American Farm Bureau Federation, which is more closely aligned with agribusiness interests, goes further, by explicitly opposing any ban on neonicotinoids and downplaying research that shows risks to pollinators.

Meanwhile, environmental experts say saving pollinators and ecosystems will take more than a new administration or state and federal bans of a few individual neonics. Real solutions may also require closing regulatory loopholes, updates to the EPA pesticide registration process, and a more concerted effort to help farmers deal with insects in less toxic ways.

“The problem is urgent enough that we really need to be doing everything that we can,” Raichel said.

Beyond Bees

Neonicotinoids are pesticides that can be sprayed directly on plants, but most are built into seed coatings. Because federal agencies only track pesticide applications, and farmers are planting instead of spraying the chemicals, reliable data on their use is sparse.

Studies have estimated between 80 and 100 percent of conventional corn acreage and 34 to 44 percent of soybean acreage are planted with treated seeds. In many places, companies no longer offer untreated seeds as an option. When they do, they often reduce the amount of replant coverage they offer if farmers choose the cheaper, uncoated seeds, driving farmers to choose the more expensive, coated seeds as a form of insurance. Neonics are also used on fruit and vegetable crops and in landscaping and pet products, and they are injected into trees to fight invasive pests.

Their systemic nature is what makes them different from past insecticides and so toxic to bees, explains Greg Loarie, an attorney at Earthjustice. Whereas an insect might have escaped unharmed if not caught in the direct line of spray before, bees can now be exposed to neonics by merely visiting a field, and they can bring the chemicals back to the hive, spreading damage.

“There’s really no way that they can avoid the insecticide when it’s infused into the plant and into the pollen and nectar,” said Loarie. Because neonics bind to nerve cells, they can affect bees in various ways. Neonic exposure can weaken a honey bee’s immune system, making it more susceptible to diseases. At certain doses, it can affect their cognition and flight ability, both of which are essential to hive maintenance. It can also affect reproduction.

“There’s really no way that [bees] can avoid the insecticide when it’s infused into the plant and into the pollen and nectar.”

Now, research shows the chemicals are not just infused in the plant, they’re also broadly contaminating the environment, exposing many organisms. As plants grow, they only take up between 1 and 10 percent of the chemical in the seed coating. The rest remains in soil and leaches into groundwater, and eventually, waterways.

Water samples taken from nine streams during the 2013 growing season in the Midwest detected neonics at every site. A 2020 NRDC report found one neonic, imidacloprid, has been detected in surface waters throughout New York State and in 30 percent of groundwater samples on Long Island. In many cases, the levels surpassed the EPA’s own benchmark for long-term harm to aquatic invertebrates.

And evidence that neonics harm those invertebrates, like plankton, is increasing. One 2019 study out of Japan demonstrated a surprisingly clear link between the introduction of imidacloprid to rice fields and the disappearance of zooplankton in a nearby lake, which ultimately led to the collapse of the fishery there because other species that ate the plankton also decreased.

Canada’s final decision on banning neonics will depend on evidenceits health agency is analyzing related to harms to aquatic insects. “The thought is that these pesticides might already be hollowing out our ecosystems from the bottom up,” Raichel said. “Our entry into this was pollinators, but . . . that ripples up the food chain.”

In August, the first long-term, national-scale study of neonicotinoids’ impacts on bird populations was published by researchers at the University of Illinois. They found neonic use had a large effect on population declines, especially among grassland birds in the Midwest, Southern California, and the Northern Great Plains. A 2017 study found that imidacloprid affected sparrows’ ability to gain weight and migrate properly.

New research points to effects on mammals, too. A 2019 study found that deer exposed to imidacloprid at levels they’d encounter in fields had an increased risk of birth defects and lower rates of fawn survival.

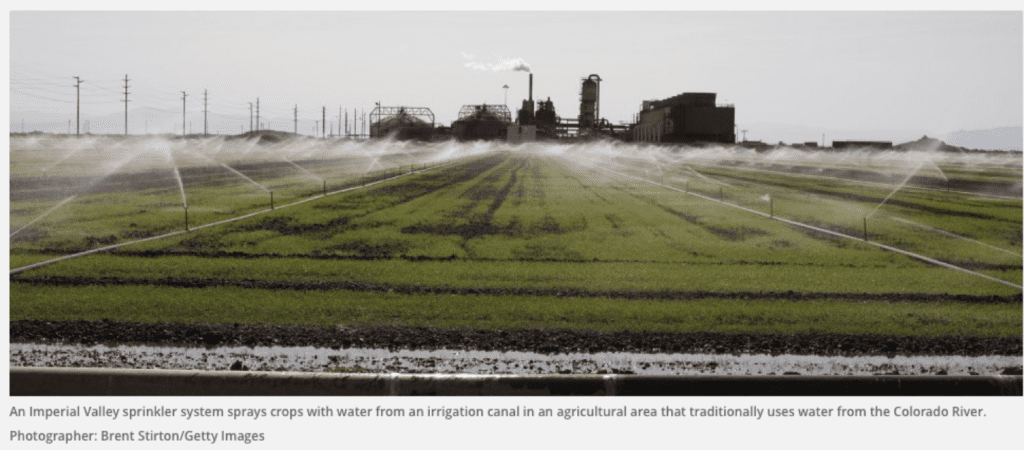

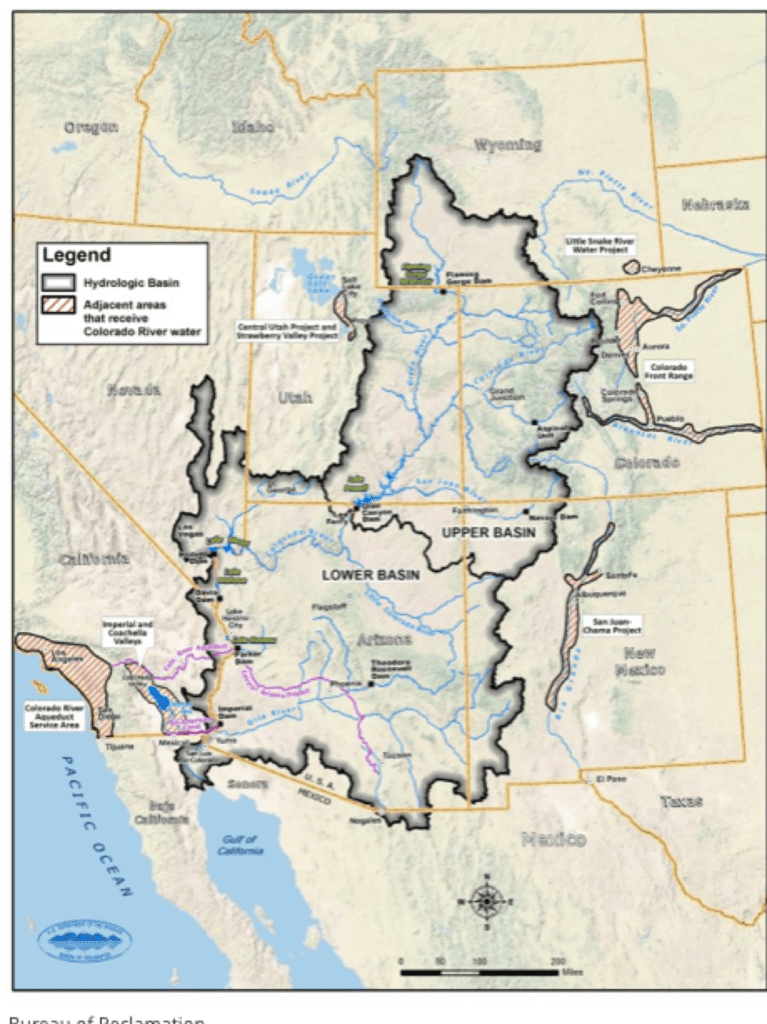

2. Colorado River Getting Saltier Sparks Calls for Federal Help. Water suppliers along the drought-stricken Colorado River hope to tackle another tricky issue after the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation installs a new leader: salty water.

The river provides water for 40 million people from Colorado to California, and helps irrigate 5.5 million acres of farm and ranchland in the U.S. But all that water also comes with 9 million tons of salt that flow through the system as it heads to Mexico, both due to natural occurrence and runoff, mostly from agriculture. Salt can hurt crop production, corrode drinking water pipes, and cause other damage Various efforts along the river or tributaries annually remove about 1.2 million tons of salt. But the largest brine-removal system in the basin has been shuttered for two years over earthquake concerns. In December, President Donald Trump’s outgoing administration released a final environmental review on what to do about it.

The chosen course: No action, leaving the fate of the project and of salt removal murky. Now local suppliers say they will be pressing the Biden administration to do the opposite.

“For the last two years the salt has been flowing back into the river,” said Bill Hasencamp, chair of the Colorado River Basin Salinity Control Forum, which represents all of the states that draw from the river. “We were very disappointed. There’s no plan to capture [it] going forward.”

Water suppliers have filed comment letters about the “no action” decision and sent letters to former Reclamation Commissioner Brenda Burman. The average annual economic loss from salinity levels in the Colorado River is estimated to be $495 million, Reclamation said in its environmental review.

Seismic Threat

At issue is the Paradox Valley Unit near the Colorado-Utah border. The project, in operation since 1996, took saline groundwater before it could hit the Colorado and the Dolores River, a tributary, and injected it more than three miles beneath the surface into a well disconnected from the river system. About 95,000 tons of salt were removed each year.

But injecting, like hydraulic fracturing, can cause seismic shifts.

Reclamation shut down Paradox Valley in March 2019 after a magnitude 4.1 earthquake, which the U.S. Geological Survey considers moderate in size. Operations resumed for a six-week test at reduced use in spring 2020, but the well currently isn’t operating.

Technical experts are evaluating next steps and it’s too soon for the agency to propose a new salinity control plan, Reclamation spokeswoman Linda Friar said in an email.

The agency currently doesn’t plan to issue a record of decision, which would finalize the “no action” plan Reclamation selected, she said.

Hasencamp, also manager of Colorado River resources for the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, and others had pushed for that delay in comments filed with Reclamation earlier this month.“I think this is going to be one of the first things the basin states is going to want to sit down about with the new commissioner,” said Chris Harris, executive director of the Colorado River Board of California during a recent meeting. “I would just hate to see us taking a step back.”

President Joe Biden has nominated New Mexico Rep. Deb Haaland as Interior Secretary and Tanya Trujillo, an expert on water law and the Colorado River, as principal deputy assistant secretary for water and science. A Reclamation commissioner hasn’t been named yet.

“We want to keep the door open for other options” beyond the “no action” alternative, Hasencamp said. “The hope is the new administration understands the importance of salt control.”

Rejected Options

In its environmental review, Reclamation considered and rejected building a new injection well, using evaporation ponds for brine to be treated at the surface, and building a discharge facility to evaporate and condense water before sending salt to a landfill.

The “no action” alternative was “in the best interest of public health and safety,” Ed Warner, Reclamation’s Western Colorado Area office manager, said in a news release.

James Eklund, former director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board, said when he served as the state’s representative on salinity control programs, he was “pretty adamant” that the bureau should switch from earthquake-causing deep injection wells to evaporating ponds in order to deal with the saltwater. Eklund is now at Denver-based Eklund Hanlon LLC.

“Oklahoma knows what can happen under that approach,” he said, citing earthquakes in the state caused by fluid waste from oil and gas production being injected deep underground.

Reclamation said in the review that without the Paradox Valley treatment, it would still be in compliance with the federal Colorado River Basin Salinity Control Act, which authorizes treatment projects to control water quality. It also announced on Jan. 19 plans to spend $1.2 million for eight desalination research projects in California, New Mexico, and Texas.

Expensive Treatment

Urban areas will be able to weather the salt problem better than agricultural ones because they have mass treatment to comply with drinking water standards, said Patricia Mulroy, former general manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority and owner of the consulting firm Sustainable Strategies.

“It’s not good for agriculture,” she said. “It’s going to make treatment more expensive.”

Mulroy is more concerned about the Colorado Riversystem’s current 20-year drought, and what it means for future operations. Reclamation forecasts show this could be one of the region’s driest years. Drought contingency plans adopted in 2019 call for reductions when Lakes Mead and Powell fall below certain levels. Mandatory water cuts for this year have already been triggered for Arizona, Nevada, and Mexico.

But that lack of water also affects water quality.

“When you have that much less water and all the salt coming in, it’s going to have even a bigger impact,” Hasencamp said. “Long-term, it’s a big deal if groundwater basins salt up.”

Expensive treatment

Urban areas will be able to weather the salt problem better than agricultural ones because they have mass treatment to comply with drinking water standards, said Patricia Mulroy, former general manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority and owner of the consulting firm Sustainable Strategies.

Asencamp said

Mulroy is more concerned about the Colorado Riversystem’s current 20-year drought, and what it means for future operations. Reclamation forecasts show this could be one of the region’s driest years. Drought contingency plans adopted in 2019 call for reductions when Lakes Mead and Powell fall below certain levels. Mandatory water cuts for this year have already been triggered for Arizona, Nevada, and Mexico.

But that lack of water also affects water quality.

“When you have that much less water and all the salt coming in, it’s going to have even a bigger impact,” Hasencamp said. “Long-term, it’s a big deal if groundwater basins salt up.” To contact the reporter on this story: Emily C. Dooley at edooley@bloombergindustry.com

Copyright EnviroInsight.org 2021