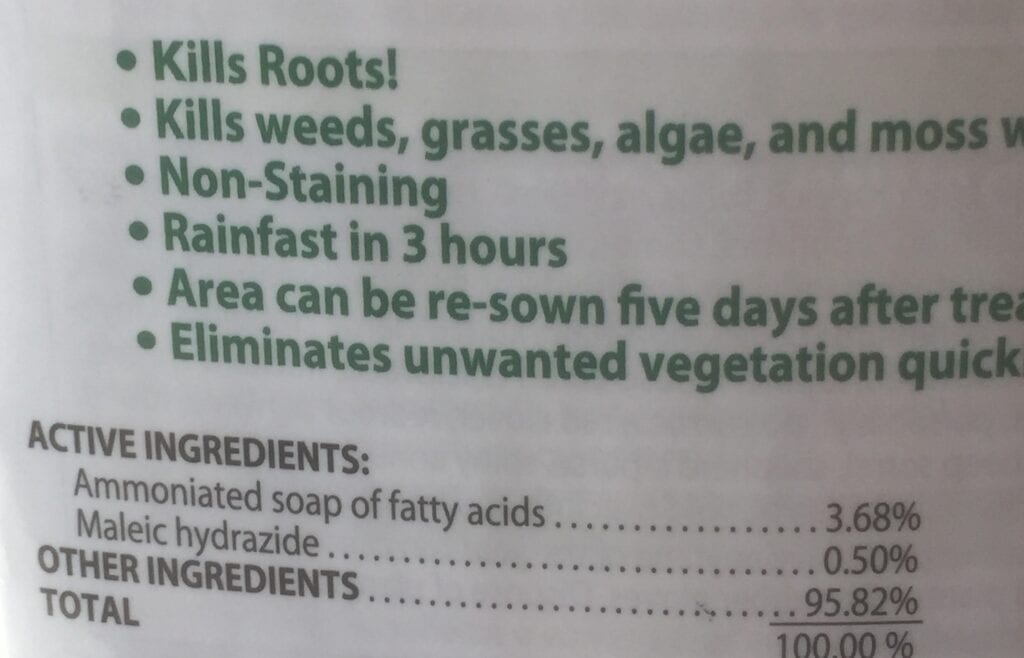

1. All Natural Weed Control – Better Than Roundup Herbacide. There is a better alternative herbicide.

The editor purchased a container of this herbicide from Lowes Home Improvement store and experimented with it on a number of weeds (Mouse Eared Chickweed, Purslane,

Puncture Weed, Lambs quarter, Mallow, nutsedge, broom sedge, etc.) in my yard, cactus garden and driveway.

All plants were observed to be in decline within three hours and were water safe in three hours and the weeds were dead within three to four days. Based on internet research on this product, it is believed this is a very adequate alternative to Roundup and the associated Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma disease. Cost for this product, $5.98 for 24 fluid ounces.

2. ADEQ Solid Waste Programs Asking For Your Input.

Solid Waste Programs

Five Year Rule Review

ADEQ invites interested community members and business and government personnel to participate in a review of ADEQ’s Solid Waste Rules. Tell us your experience, comments, or feedback on these rules through the survey below.

Go to Survey >

Responses are due no later than Nov. 29, 2019

Read the Chapter 13 Rules at www.aac/R18-13

For questions, please contact: Mark Lewandowski

Waste Programs Division

[email protected]

3. 2019 Is Coming To Close: Time To Improve Your Tax Situation While Helping Non-Profits. Before the end of 2019, please consider donating to your favorite non-profit charity organization before the year comes to an end. Donations to non-profits for Federal tax purposes are multi-fold, such as Heifer International and EnviroInsight.org.

If you want to to deduct dollar for dollar, consider donating to your local Foster Care Charitable Organization for 2019. There is a limit on how much an individual or married couple can donate. See participating list at https://azdor.gov/sites/default/files/CREDITS_2019_qfco.pdf

It’s your money, use it wisely!

4. Irrigation Water Consumption Continues To Drop. The average amount of irrigation water applied to a field was 1.5 acre-feet per acre in 2018. That number comes from the Irrigation and Water Management Survey, which is conducted every five years.

In 2013, the average was 1.6 acre-feet per acre, and in 2008, it was 1.7 acre-feet per acre.

5. NAU Climate Summit Sparks Conversations On Drying Landscapes, Rising Temperatures And Fire. As northern Arizona’s forests dry and temperatures rise, all levels of fire management and science are reading the signs of heating global temperatures locally and trying to change with the climbing temperatures.

Environmental experts from around Arizona traveled to Flagstaff this past Friday and Saturday for Northern Arizona University’s Climate Summit 2020. The two-day conference included a hip-hop performance by activist Xiuhtezcatl Martinez, documentary viewings, and panel discussion on topics like drought, wildfire, climate education, and both rural and urban impacts. In their panel on wildfire, four current leaders from around the state, and one from California, came to talk about the way fire response and study is changing.

Pete Fule, a forest ecologist at NAU’s school of forestry, started off his time on the wildfire panel saying the hottest five years have been the last five years, according to National Weather Service data.

“You can just keep on saying that, because it will probably be true next year and the following year and so on,” Fule said.

As Flagstaff’s temperatures have increased, years of federal suppression of forest fires have caused increasingly dry fuels on the forest floor to be quick to light, Fule said. And as fire seasons last longer, fires will become larger and more extreme.

Fule said the city’s environment will change. He believes there are two cities that can be used as a comparison: Prescott and Gallup, N.M. Fule hopes that in the next 10 to 20 years Flagstaff will feel like Gallup, whose mean annual temperature is 48.7 degrees Fahrenheit, as opposed to Flagstaff’s 46.3 degrees. But he acknowledges that Prescott, with a mean of 54.8 degrees, is also an option.

“Prescott is a nice place, but it does not have the forest ecosystem that we have here in Flagstaff,” Fule said. “And since this is one of the places that are still in high elevation, just imagine what Tucson and Phoenix will be like.”

Numbers of fires and the cost of suppression are both going up, and while the quantity of fires isn’t increasing much, the size of the fires is, according to Aaron Green, assistant state forester with the Department of Forest and Fire Management.

“Where once a fire here on the Coconino National Forest, a large fire, would be 1,000 or 5,000 acres, now large fires are measured in hundreds of thousands of acres,” Green said. Source: Flagstaff Sun

6. Non-Resident Decals Now Required For Out-Of-State Off-Road Vehicles. Dee Pfleger of Arizona Game & Fish speaks to the Arizona Peace Trail group at their Nov. 13 meeting. Pfleger was there partly to explain the state’s new law that requires off-road vehicles registered in other states to obtain a non-resident decal before they can be driven off-road in Arizona.

7. Streams In The Danger Zone. The streams and watersheds of Rim Country and the WhiteMountains face just such a potential for disaster, according to the environmental impact statement (EIS) for the 1.2 million-acre Four Forest Restoration Initiative Rim Country project. They’re already struggling — and likely to get lots worse. There is an effort to save Arizona’s forests through a mix of thinning, logging and prescribed burns, we’ll look at the danger faced by the region’s streams and watersheds. They sustain the wildlife, forested towns like Payson and Show Low and even millions of Valley residents. However, a century of mismanagement has converted the once fire-adapted, low-density, diverse forest with 50 or 100 trees per acre into a tinderbox, with 1,000 trees. The most vital ecosystem in that forest faces the greatest danger.

Turns out, some 27 percent of the 21,000 acres of riparian areas and wetlands in the 1.2-million-acre study area are already in “poor” condition, according to the EIS, now available for public study and comment on the Forest Service’s 4FRI website. Another 58 percent are in “fair” condition.

The study area includes 4,200 miles of stream courses — but most only carry water after a rain. The area includes 667 miles of intermittent streams and only 169 miles of permanent streams like the East Verde, Tonto Creek, Haigler Creek, the White River, Silver Creek and the Black River.

However, those riparian areas remain critical to some 80 percent of the wildlife. Step back from the stream and consider the condition of the watersheds themselves. Those watersheds supply the reservoirs and water tables.

However, only 15 percent are rated as “functioning properly.” Some 83 percent are considered at risk, which means the streams drying up or silting up. The slopes are prey to dangerous erosion, the soils are washing away or wildfires have caused worrisome changes in water absorption and runoff. Some 2 percent of those watersheds are considered “at risk,” according to the EIS.

Most of them carry a dwindling amount of water thanks to that increase in tree densities. Many also face problems with water quality, including bacteria, metals and other pollutants caused by faltering septic systems or runoff from urban areas and mine tailings.

Even the soil is in trouble. The tree thickets keep the sun from hitting the forest floor and have piled up 20 or 30 tons of pine needles and branches on almost every acre. A fire or other disturbance that breaks through that matter would leave the rootless soil prey to erosion, according to the EIS.

Some 70,000 acres in the study area already has “impaired” or “unsatisfactory” soil conditions. It gets worse.

Almost three-quarters of the forest is now vulnerable to a high intensity active or passive crown fire. Such a high intensity fire would destroy already vulnerable riparian areas and watersheds.

For starters, the seared soil can no longer absorb water normally. As a result, erosion can increase a thousandfold in the wake of a high intensity fire.

After the Schultz Fire caused a monsoon flood that wiped out dozens of houses and killed a little girl, Flagstaff did a study on what a similar fire on the forested slopes above the city would produce. The answer: A billion dollars in flood damage that could wipe out Flagstaff’s historic downtown.

Such a flood can fill in reservoirs. Denver spent hundreds of millions dredging a city reservoir after a wildfire. Storm models suggest that Flagstaff’s Lake Mary, Payson’s C.C. Cragin Reservoir and even Salt River Project’s Roosevelt Lake could all suffer flooding.

Moreover, an advancing crown fire could consume normally fire-resistant riparian plants.

Finally, the floods that follow a high intensity crown fire can smother streams with silt and debris. That’s what happened to Dude Creek after the Dude Fire nearly 30 years ago. Arizona Game and Fish had even introduced a population of native Gila trout into that stream, but silt after the Dude Fire wiped them out.

So a high intensity wildfire could have devastating consequences throughout the 1.2 million acre study area where 43 percent of the ponderosa pine and mixed conifer areas already face a “moderate to severe” threat of erosion. Some 400,000 acres have slope that are 14 to 40 percent. Another 300,000 acres have slopes greater than 40 percent.

So will a combination of thinning and controlled burns get us out of this mess? Not without some short-term damage, concluded the EIS.

The thinning projects would involve a lot of soil disturbance as loggers cut down many of the trees smaller than 18 inches in diameter, load them onto trucks and haul them away on hundreds of miles of new, temporary roads.

One study found a 40-fold increase in erosion in the year after a thinning project and a tenfold increase in erosion in the second year. However, by the third year erosion rates had returned to normal.

The EIS listed all kinds of short-term impacts from the preferred Alternative 2, which would treat 900,000 acres with a combination of thinning projects and controlled burns. The alternative would also disturb 61,000 acres by building roads and other infrastructure to support the massive increase in thinning projects. The treatments would also restore 184 springs, restore stream habitat along 777 miles, decommission 1,300 miles of roads, construct 300 miles of temporary roads, and put up 200 miles of protective barriers around springs and groves of aspen, native willows and big-toothed maple.

But that’s nothing compared to doing nothing.

The analysis estimates that at least a third of the forest will suffer high-severity crown fire burns in the next 20 years if nothing is done.

The fire danger’s likely to get much worse — and not just because of the tree thickets. The climate’s also heating up, making fires far worse and streams more stressed.

The overwhelming scientific consensus predicts a roughly 8-degree increase in average temperatures in Arizona by the end of this century in part because of human activities that have increased heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere, concluded the EIS.

Some studies have suggested a steady rise in temperatures could change high-altitude weather patterns in a way that could eliminate or diminish the Arizona monsoon. Without the monsoon, the fire season would dramatically increase.

Other studies have suggested the increased energy in the atmosphere could actually suck up more water from the ocean and increase rainfall in some areas.

Most likely, we face a future with hotter days, a smaller snowpack, longer droughts and more extreme weather. All that could make the shift to an era of mega fires worse.

“While the future of climate change and its effects across the Southwest remains uncertain, it is certain that climate variability will continue to occur across the project area — with higher probabilities of extended drought, which can lead to dramatic effects on the landscape.”

Just keep that in mind, next time you sit next to a mountain stream.Listen to the water burble. But keep your eye on the sky.