1. Arizona Water Law Conference. August 1st through August 2nd at the Scottsdale Hilton Resort & Villas, located at 6333 North Scottsdale Road, Scottsdale, 85250. Cost is:

| $995 per person | Government or Non-profit |

| $ 895 each for 2 or more | $895 per person |

| $ 795 each for 5 or more | $795 each for 2 or more |

| $695 each for 5 or more |

Some of the topics to be discussed include:

- The drought contingency plan

- Water Quality

- The Gila and Little Colorado Adjudications

- Assured Water Supply

- Effluent Reuse Regulation

- Surface and Groundwater Updates

- Water and Beer

- Tribal Water Issues

- And more (like a private Beer Tasting and Networking Happy Hour, sponsored by AZ Wilderness Brewing Company)

Audio Home Study Course available after the conference for $995. Audio transcript and Course materials.

Course materials only, available after the conference for $250

To register and get additional information : www.cle.com/ArizonaWaterLawConference

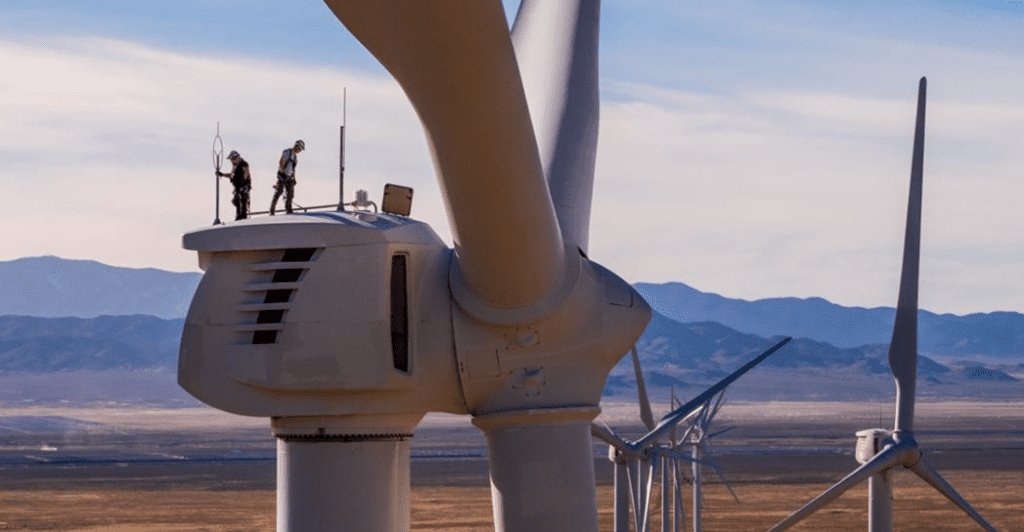

2. Utah’s Clean Energy The Utah Way to Achieving 100 Percent Clean Energy How a politically conservative state set aggressive goals for clean energy

IT’S IMPOSSIBLE TO VIEW the Salt Lake City skyline without noting six castle-like spires, at the top of which stands the golden statue of Angel Moroni blowing his horn. The famous towers of the Latter-day Saints temple rise in the city’s midst, framed by the snowcapped Wasatch Range. To the west stand the three concrete stacks of the Gadsby power plant. Owned and operated by the state’s dominant electric utility, Rocky Mountain Power, the plant once burned coal but switched to gas in the 1990s. Though most photographers crop images of the city to omit them, Gadsby’s triple stacks are visible from almost any vantage point in the Salt Lake Valley—a seeming monument to the state’s historic reliance on coal.

They also mark the place where Utah’s carbon legacy may have come to an end.

In March 2016, Park City passed a resolution committing the city to transitioning 100 percent of its energy to renewable sources by 2032. Then in July 2016, Salt Lake City announced its own commitment. Moab, the redrock mecca, did the same at the beginning of 2017, followed later that year by Summit County. Soon after, Salt Lake suburbs such as Cottonwood Heights also joined in.

The commitments, which took the form of joint resolutions establishing community-wide goals For clean energy, transcended traditional political norms and reflected a growing understanding among the state’s elected officials, environmental advocates, and industry and business leaders:

They had no choice but to act on climate. The state is getting hotter, and snow is melting earlier, threatening not only the tourism and recreation industry on which many livelihoods depend but also the water supply.

Yet one very big puzzle still had to be solved. For these resolutions to succeed, cities needed the buy-in of Rocky Mountain Power—a state-regulated monopoly operated by PacifiCorp that for generations has been notorious for burning coal. Utah cities, except for a handful that produce their own power, are legally required to buy energy from the utility. Any Utah city that wanted to switch to renewable energy had two choices: start its own electric utility from scratch or convince the coal-reliant utility to join it.

Utah governor Gary Herbert signed it into law, and Rocky Mountain Power publicly embraced it. What started as a years-long grassroots movement to abandon dirty energy evolved into the sort of private negotiation process that local politicians, to the amusement and occasional dismay of residents, have dubbed “the Utah way.” Faced with a populace that is known for strong opinions about agreeableness, advocates knew that climate action would require an especially collaborative approach.

Carey realized that one of the biggest threats to the ski industry he loved was climate change. Approximately 70 percent of Park City’s economy depends on winter recreation. In April 2019, Climate Central released a report listing the five states in the country warming the fastest. Utah came in at number five, with a 3.02°F increase in the average temperature over the past 48 years.

Then in 2015, the council announced it was crafting a new slate of policy goals for the city and invited residents to offer their feedback at a meeting. Carey rallied his employees and organized grassroots activists to convince residents that clean energy should be one of those goals. The effort paid off; dozens of people turned out to the meeting.

Luke Cartin, the environmental sustainability manager for Park City, was impressed. “When you have 50 to 150 people show up at a city council meeting demanding action and no one speaking in opposition, the city council feels the urge—this is a priority.”

The city council agreed to make energy and climate change Park City priorities. Council members suggested a benchmark for achieving 100 percent renewable energy at some point between 2040 and 2050; Carey feared that was insufficient and recommended 2030. The council members concurred, setting a goal of 2032, which they later dropped to 2030 when Salt Lake City was selected as a possible location for the Winter Olympics.

Carey is just one grassroots activist among many who came together to compel Park City officials to act. Not long after the meeting, the city launched a series of initiatives—from solar on almost every public facility to an all-electric bus fleet—and formally passed a resolution committing to clean energy. Park City, with a population just shy of 10,000, had emerged as a climate leader in the state. But city leaders quickly determined that cityproduced clean energy would be cost-prohibitive. To be successful, they would need Rocky Mountain Power to generate as much renewable energy as the city typically uses in a year.

They soon learned that a conversation with the utility had already quietly begun in Salt Lake City. It was a discussion led by two women, both of whom had just assumed their positions: the mayor of Salt Lake City and the CEO of Rocky Mountain Power.

“People want to do good and be a part of something, and people want to help out with climate change, but they don’t know what to do,” Carey says. “It’s actually really easy to motivate what they call the ‘climate army.’ But you have to show people the way.” Source: GreenWay

3. AZAEP July Monthly Meeting Speaker: Tessa Nicolet, U.S. Forest Service Topic: Fire Ecology in the Southwestern United States

This presentation will focus on the history of fire across the west and its evolving relationship with ecosystem health and management. Fire has always had an important ecological role to play in our southwestern ecosystems. Fire management has evolved over the past century to attempt to adapt to our growing understanding of the role of fire. This presentation will highlight the current science and research of fire and how it is being applied to our landscapes.

Tessa Nicolet is a Regional Fire Ecologist the U.S. Forest Service, Southwestern Region station in Payson, AZ. Her responsibilities include training, analysis support and transfer of best available science relating to fire and fuels management, fire ecology, fire regimes, fire risk, and behavior analysis modeling, vegetation monitoring, and ecosystem restoration to fire professionals across the Southwest. She received a Masters of Forestry with an emphasis in Fire Ecology from Northern Arizona University.

Date: Tuesday, July 23, 2019 Time: 6 p.m. to 8 p.m. Location: Macayo’s in Tempe 300 S. Ash Avenue, Tempe, AZ 85281

RSVP here or by sending an email to azaep@azaep.org

Please Note: We are currently unable to take PayPal payments through our website. To pay your monthly meeting dues, please bring cash or check to the meeting, or we can note an IOU on our account and collect payment once our PayPal is available. We apologize for any inconvenience this may cause.

4. Do You Keep Bottled Water In Your Car For That Just-In-Case Moment?

Not a good idea. First, always check the bottom of the plastic bottle for the number that determines the plastic material used in making the bottle. If the number is a “1” or “2” you’re okay. Numbers 3 (Polyvinyl Chloride), number 6 (Polystyrene) or 7 (other but seems to always contain Bisphenol A (BPA).

BPA is found inside soup cans to prevent rust and many other products. BPA has been found to act as a hormone disrupter where synthetic chemicals called xenoestrogens mimic estrogen. In one study, BPA was named as the proliferation of cancer cells.

When you leave your car once you get home, take your number 1 or 2 plastic bottle inside with you. When finished with a disposable, remove the lid, squish the bottle and then return the cap to the bottle. Check your local material recycling facility for specific instruction. Better yet, use a glass bottle with a shatter proof cozy or covering.

5. A Plastic Alternative Is Now Available On The Local Level.

If you have read any newspaper, news magazine, watched television or listened to radio news, you know that China has cut off accepting U.S. recycling waste due to our lack of cleaning the waste.

Plastic soda cups and plastic straws are a large part of the debris found in sewer flows and oceanic floating islands.

There is now an alternative that is available to all of us who shop Fry’s Grocery stores,

and you have a choice.

One finished with your drink, shake or smoothie, simply rinse the straw ( say “NO” to a plastic cap) cup, and then toss them into the recycling bin. Easy bio-reduction and a big plus for the environment. Give them a try!

Copyright 2019 Enviroinsight.org