1. Celebrating The 4th Of July!

Diversity:

: the state of being diverse; variety. A range of different things.

: the condition of having or being composed of differing elements : VARIETY especially : the inclusion of different types of people (such as people of different races or cultures) in a group or organization programs intended to promote diversity in schools.

The 4th of July or July 4th, also known as Independence Day, is a federal holiday on July 4th. It marks the adoption of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776 when the United States declared independence from Great Britain. The day is the “National Day” of the United States. Later in the history of the Early Republic, the observance of Constitution Citizenship Day marks when the Constitution was signed on September 17, 1787 for all of us.

2. The US Recycling System Is Garbage. China doesn’t want our crap anymore, and who can blame them? What’s Happened?

FOR NEARLY THREE DECADES your recycling bin contained a dirty secret: Half the plastic and much of the paper you put into it did not go to your local recycling center. Instead, it was stuffed onto giant container ships and sold to China.

Around 1992, US cities and trash companies started offshoring their most contaminated, least valuable “recyclables” to a China that was desperate for raw materials. There, the dirty bales of mixed paper and plastic were processed under the laxest of environmental controls. Much of it was simply dumped, washing down rivers to feed the crisis of ocean plastic pollution. Meanwhile, America’s once-robust capability to sort, clean, and recycle its own waste deteriorated. Why invest in expensive technology and labor when the mess could easily be bundled off to China?

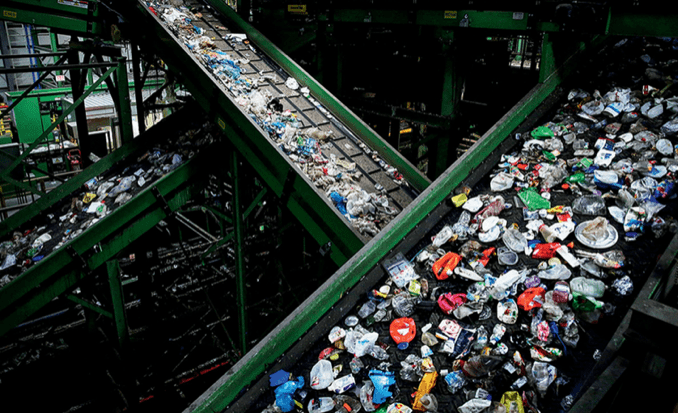

Then in 2018, as part of a domestic crackdown on pollution, China banned imports of dirty foreign garbage. In the United States, the move was depicted almost as an act of aggression. (It didn’t help that the Chinese name for the crackdown translated as National Sword.) Massive amounts of poor-quality recyclables began piling up at US ports and warehouses. Cities and towns started hiking trash-collection fees or curtailing recycling programs, and headlines asserted the “death of recycling” and a “recycling crisis.”

But a funny thing happened on recycling’s road to the graveyard. China’s decision to stop serving as the world’s trash compactor forced a long-overdue day of reckoning—and sparked a movement to fix a dysfunctional industry. “The whole crisis narrative has been wrong,” says Steve Alexander, president of the Association of Plastic Recyclers. “China didn’t break recycling. It has given us the opportunity to begin investing in the infrastructure we need in order to do it better.”

“That’s the silver lining in National Sword,” adds David Allaway, a senior policy analyst for Oregon’s Department of Environmental Quality and the coauthor of a surprising new study that demonstrates the ecological downsides of pursuing recycling at any cost (see “When Recycling Isn’t Worth It“). “China finally is doing the responsible thing, forcing the recycling industry to rebuild its ability to sort properly and to focus on quality as much as it previously focused on quantity.”

Paradoxically, Allaway says, part of America’s trash problem arose from people trying to recycle too much. Well-meaning “aspirational” recyclers routinely confuse theoretical recyclability with actual recycling. While plastic straws, grocery bags, eating utensils, yogurt containers, and takeout food clamshells are all theoretically recyclable, they are almost never recycled. Instead, they jam machinery and lower the value of the profitably recyclable materials they are mixed with, like aluminum cans and clean paper. In addition, Americans are notorious for putting pretty much anything into recycling bins, from dirty diapers to lawn furniture, partly out of ignorance and partly because China gave us a decades-long pass on making distinctions.

“We need to recycle better and recycle smarter,” Allaway says, “which means recycling only when the positive environmental impacts outweigh the negative.”

MARTIN BOURQUE is the executive director of the Ecology Center, the nonprofit that handles curbside recycling for Berkeley, California. During the early days of recycling, in the 1970s and ’80s, he says, US consumers routinely cleaned their recyclables of food residues and separated materials. Berkeley residents originally sorted recyclables into seven categories, including by color of glass.

That system changed in the 1990s, when a rapidly industrializing China started to aggressively import mixed paper and plastics from western countries to get feedstock for the products that it was manufacturing and exporting back to those same countries. This coincided with a consolidation of the US trash business into the current dominance of a few large corporations, which were happy to let China do all the work. US trash collectors and recycling facilities found that they could elevate quantity above quality and make more than $20 a ton doing so.

Offshoring cut labor and transportation costs and reduced the need to update sorting and cleaning machinery. Cities and waste companies abandoned methodical curbside sorting in favor of the far cheaper and now predominant single-stream method, in which all recyclables go into one bin that’s picked up by one trash truck. Only minimal sorting by the collectors was required, as different kinds of plastic (including types that can’t be recycled) could be packaged into giant, stinky bales. People felt virtuous throwing most everything into the recycling bin.

Mixed paper could be bundled in the same way, much of it contaminated from mingling in the bin with dirty dog food cans and worse. These bales would be taken to the nearest port and loaded onto container ships bound for China—4,000 containers a day prior to 2018. Other countries did the same, and by 2016, China was importing more than half of the world’s plastic and paper trash.

As much as 30 percent of those single-stream recyclables was contaminated by nonrecyclable materials, Bourque says. Many of the bales of plastic sent to China were worthless and were never even recycled. Instead, they ended up polluting land and ocean outside China’s impoverished, unhealthy “recycling villages,” the shantytowns full of mom-and-pop recycling businesses that lined the edges of China’s big port cities, reeking from caustic chemicals and burning garbage.

A 2015 study coauthored by Jambeck found that 1.3 million to 3.5 million metric tons of plastic flowed into the ocean from Chinese coastal sources each year.

But now China has a burgeoning middle class and its own growing consumer economy with its own waste and recyclables, leaving little appetite for trash from other countries. Jambeck is among those who believe that National Sword’s import ban, along with China’s efforts to clean up the recycling villages and construct clean, state-of-the-art sorting and recycling facilities, is helping to stem a crisis more than it is causing one. “China’s regulatory action exposed a sore that was already there,” she says. “People weren’t noticing since it had a bandage on it.”

As early as 2013, China began warning US recyclers that it intended to address its own environmental problems and would limit contamination of recycling imports to 0.5 percent. (The mixed bales of paper and plastic the United States was shipping to China typically had 30 to 50 times that level.) But few believed that China would carry out its threat, so when the new rules came, US recyclers were caught with their polyester pants down, incapable of cleaning their recyclables enough to meet China’s new standards, let alone those of US manufacturers seeking recycled feedstock.

The lack of preparation for China’s import ban created pain and chaos in communities across America. Some recyclers, predictably, began searching for countries desperate enough to fill in for China. Vietnam, Malaysia, and others did so for a time, only to be overwhelmed by the stinking tide. (Vietnam and Malaysia have since shut the imports down.) Prices for recyclables dropped to a fraction of what China once paid, often far below the cost of gathering and shipping the material. Bales of mixed paper that previously sold for $155 a ton could barely fetch $10. “What this crisis is really about,” says Vinod Singh, outreach manager for Far West Recycling in Portland, Oregon, “is shifting from the artificial situation China created, in which recycling more than paid for itself as a commodity, to the new reality of recycling as a cost.”

The economics were shocking. Stamford, Connecticut, went from earning $95,000 from its recyclables in 2017 to paying $700,000 in 2018 to get rid of them. Prince George’s County, Maryland, went from earning $750,000 to losing $2.7 million. And Bakersfield, California, swung from earning $65 a ton for its combined recyclables (glass, plastic, paper, metal) to paying $25 a ton. “Recycling facilities seemed to be spinning gold with China dominating the market,” Singh says, “but it was an illusion that could not last.”

Remove contents, such as food waste, from containers before recycling.

Some communities started sending their overflowing recyclables to the landfill, as happened in Portland and elsewhere in Oregon, or to be incinerated at waste-to-energy plants, as in Philadelphia. Many localities were forced into a combination of rate increases for collection (most ranging from $2 to $3 a month for homeowners) and limiting curbside recycling of plastics to two or three types instead of all seven—a route taken by Hannibal, Missouri, among others. Some towns stopped recycling glass and shredded paper as well; no one wants to pay for used glass, it seems, and shredded paper confounds sorting machinery. Columbia County, New York, will charge residents $50 a year to be able to bring their recyclables to a drop-off depot. And some communities that had curbside programs have ended them altogether, including Deltona, Florida; Enterprise, Alabama; and Gouldsboro, Maine.

“RECYCLING IS SUPPOSED to be the last resort after reduction and reuse,” says Bourque, and Berkeley’s Ecology Center continues to find innovative ways to push the issue, most recently in a new city ordinance to take effect in January 2020 that will impose a 25-cent charge on all disposable cups sold in the city, including coffee cups. “Why are people sitting around for hours in coffee shops drinking out of paper cups?” Bourque asks. “It’s absurd when reusable ceramic cups are such a better option.” In addition, disposable utensils, straws, and napkins in eating establishments and coffee shops will be available only upon request or at self-serve stations; takeout food must come with compostable containers and utensils; dine-in food must be served on reusable dinnerware

“This ordinance is focused on upstream impacts. We all should be reducing the purchase of packaged goods or at least packaged goods with reduced packaging,”reuse various packaging, and repurpose, and clean your recyclables of grease, food and debris that makes your recyclables un-recyclable. You see, it is up to all of us.

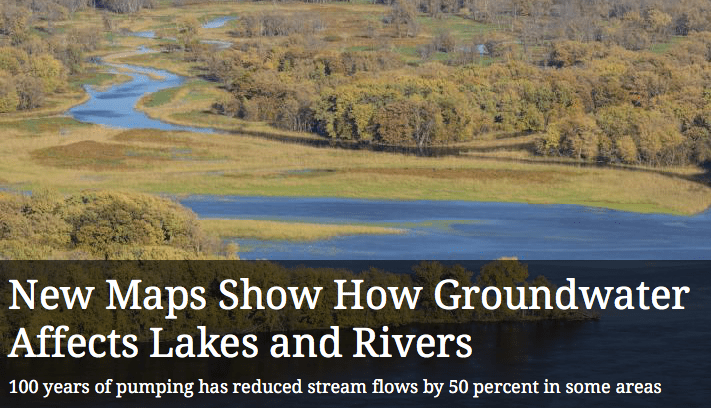

On the surface, it’s pretty obvious how humans have altered lakes and rivers over the past century; dams have turned rivers into strings of reservoirs, the Mississippi River is more or less a concrete-lined sluice, and artificial ponds have proliferated by the thousands. Less apparent, but perhaps just as important, is how tapping into the groundwater systems that underlie the United States has impacted those streams and lakes as well. Now, a new detailed study in the journal Science Advances shows how much groundwater pumping has impacted those water bodies, in some cases reducing their flows by half.

Researchers have mapped the impact of groundwater pumping on surface water in individual watersheds before. But it’s only recently that computing power has improved enough to look at groundwater’s interaction with surface water, known as integrated modeling, on a scale as large as the United States. That’s what University of Arizona hydrologist Laura Condon and her coauthor Max Reed of the Colorado School of Mines decided to tackle in their new study. They mapped out most of the mainland United States excluding the coasts into squares 0.6 miles on each side, 32 million squares in all.

They then input data about groundwater down to 328 feet, temperature, precipitation, overland water flow, lateral groundwater flow, transpiration, and all the other factors that impact groundwater levels. The team ran computer simulations, one showing what the hydrologic system—rivers, streams, and lakes—looked like before larger-scale pumping began. The second shows how those systems behave after 100 years in which humans have pumped out 649 million acre-feet of groundwater, enough to flood the Intermountain West, plus most of California, with a foot of water.

The simulation found that all that pumping has radically reshaped the surface water in some places, especially those with a shallow water table, about two to 33 feet below the surface. Western Nebraska, western Kansas, eastern Colorado, and parts of the High Plains in particular have seen some streams and rivers where the flow of water has decreased by 50 percent; in some locations, the streams have simply dried up. The dropping water table makes future pumping more difficult and more expensive; lower groundwater levels can impact ecosystems like wetlands and kill off keystone species like cottonwood trees.

“We showed that because we’ve taken all of this water out of the subsurface, that has had really big impacts on how our land surface hydrology behaves,” Condon said in a statement. “We can show in our simulation that by taking out this groundwater, we have dried up lots of small streams across the US because those streams would have been fed by groundwater discharge.”

It turns out that groundwater is an important buffer for many surface streams and lakes and vegetation. In dry years, groundwater seeps into lakes or streams, bolstering water levels. The same goes for trees and plants—even when precipitation is below average, a robust groundwater supply can help tide them over for a few bad seasons. But pump that water out and those ecosystems no longer have a natural safety net.

There are other consequences of overdrawing from underground aquifers. In coastal areas, it can lead to incursions of seawater and in other areas can lead to groundwater contamination, lowering of the water table, and land subsidence.

A couple of big rainstorms, in most cases, are not enough to recharge groundwater supplies. It often takes a long time for precipitation to infiltrate the water table, meaning it’s hard to recharge groundwater as quickly as its pumped out. That means managing subsurface water is critical. “The crazy thing about our groundwater system is that it’s both a pro and a con. It’s really slow moving, which is great because it will buffer out our wet and our dry years, because when we have a dry year, the groundwater doesn’t respond instantly, and we still have water that can discharge into our streams,” Condon says.

For instance, after California’s drought officially ended earlier this year, many surface reservoirs were on the rebound. But years of pumping have decimated groundwater supplies, which may take much, much longer to recharge.

Groundwater only accounts for about 25 percent of available freshwater in the United States. But in western states and areas of the Southwest where surface water is hard to come by, it’s particularly important. That’s why all of those states have implemented groundwater management regulations, with California, the last to do so, passing its Sustainable Groundwater Management Act in 2014, which requires permits to pump in certain basins. Prior to that, the law more or less said if you can pump it, the water is yours.

Currently, the legal framework surrounding groundwater varies from state to state and is a highly complex legal nightmare involving property rights, the public interest, and in a few select cases, ecological impacts. That’s why the Water in the West program, a joint venture between Stanford University and the Bill Lane Center for the American West recently launched its License to Pump dashboard, a visual representation of the groundwater basins and pumping regulations surrounding them in hopes of clarifying the issues. “Some things are just best done visually, even in nuanced fields like the law,” Geoff McGhee, the explanatory journalist who co-created the project said in a statement.

Condon hopes that her new maps will also help people visualize the landscape of unseen groundwater and will help integrate conversations about groundwater and surface water. “I hope that this study really helps raise awareness with the broader public about how connected groundwater and surface water are. If we’re using groundwater, we don’t just have to worry about running out of groundwater someday,” she says. “We also have to worry about the fact that when we’re drying out the subsurface, and we can be taking water from streams, we can be taking water from plants and that we can be losing this really important buffer that helps us sustain ecosystems.”

Copyrright EnviroInsight.org 2019