1. Fluorescent Evergreen Glow Tells When Trees Are Taking Up Carbon.

It’s pretty simple to tell when deciduous trees are photosynthesizing—their leaves are green. When that process is over for the year, the foliage shrivels up, turns brown, and falls off, an event so widespread it can be tracked by satellites in space. But tracking when evergreen trees crank up their chloroplasts and begin turning sunlight and CO2 into energy is much more difficult since, as their name implies, they stay green year-round (the trees actually stop photosynthesizing in the autumn but use a green pigment as a type of sunblock, keeping them green year-round). That has been a problem when it comes to climate modeling, which currently relies on estimates to determine how much CO2 evergreen forests pull out of the atmosphere. But a new study suggests there’s another way to keep tabs on photosynthesis in evergreen forests: watching their fluorescent glow from space.

Decades ago, researchers realized that chlorophyll gives off a tiny, difficult-to-detect fluorescent glow. When sunlight hits chlorophyll—the green pigment that produces energy in most plants—it bumps it into an excited energy state. When the chlorophyll returns to its normal state, it emits 2 to 4 percent of that energy as a photon, or light particle, in the red and far-red light wavelengths. The glow is called solar-induced fluorescence (SIF) and, though not visible to the naked eye, it can be picked up by spectrometers, sensitive instruments that detect wavelengths of light.

In 2011, researchers first used satellite data to measure plant fluorescence, but scientists are still figuring out what the glow actually means. “Because they’re always green, it’s harder to know when photosynthesis might ramp up and when it might ramp down in evergreens,” says Troy Magney of the California Institute of Technology and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, first author of the new study in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. “Beyond that, the typical remote sensing techniques we use to look at evergreen species basically just measure the amount of reflected radiation in the near infrared and red spectrum, which really just tells us how much green stuff there is. But we really don’t know what that green stuff is doing. We have no idea when they start photosynthesis and how much carbon they take up.”

Magney and his colleagues decided to see if they could learn to pull more information out of the glow of the pines. To do so, they built a tower in The middle of the subalpine conifer forest at Niwot Ridge, an ecology research station outside Boulder, Colorado. They outfitted the tower with a spanning spectrometer, which kept track of the SIF coming off the surrounding forest, tracking both daily and seasonal cycles from June 2017 to June 2018. They also investigated some of the trees themselves to see if the fluorescence corresponded to real-world upticks and decreases in photosynthesis. The SIF, it turns out, is a pretty good measure of photosynthesis, meaning tracking evergreen fluorescence is a viable way to measure the energy produced by photosynthesis, or gross primary production, of the forests.

Not only could the technique finally give researchers a good handle on the amount of carbon evergreens pull in, it could also be used to monitor forest health since photosynthesis is likely to drop in the early stages of drought, insect infestation, or the advent of tree diseases. Currently, researchers don’t usually know a forest is in trouble until large swathes are dead or dying.

The technique could also solve several mysteries about pine forests. Whereas pines in the boreal forest or alpine regions shut off photosynthesis for the winter, it’s believed that conifers in the southeastern United States keep producing at least some energy all year round. Monitoring the SIF of those forests could provide an answer to how much energy they produce in the winter months.

It could also help researchers untangle the life cycle of evergreen forests. It’s believed that younger forests are a net carbon sink—they pull more carbon out of the atmosphere than they produce. But at a certain point, Magney says, it’s believed that they become a carbon source—older forests stay green even as the trees within them begin the long, slow process of dying, which releases CO2.

“I would say the general consensus is confusion as to the fate of evergreen forests,” Magney says. “There’s been a debate for decades about whether the boreal forest is greening or browning. Both are happening, but we don’t know what’s driving it. Combining these new techniques with information on soil moisture, air temperature, humidity, and other factors we could find out.”

The study has already led to one surprise. Using the SIF data, the team found that when photosynthesis kicks in at springtime, it’s not a gradual process. The pines in Colorado ramped up from dormant to producing maximum energy in two weeks, much quicker than hypothesized.

The team is currently working on a supersize version of the experiment and over the last year installed six more towers in various forests, including Costa Rica, Saskatchewan, and Alaska, which they hope will teach them how to properly interpret the fluorescence data coming from space.

Currently, two NASA probes are capable of providing SIF data: the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2, launched in 2014, and the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-3, a module attached to the space station, launched just last month. But the team hopes that future satellite missions will include even more sensitive spectrometers to provide fine-grained data. Currently, the sensors in orbit measure areas of about one by two kilometers. Magney says something with pixels representing 100 by 100 meters would be more useful. Source: : Sierra, June 9, 2019

2. Understand Using Cardboard As A Mulch For Your Garden.

Cardboard can be a great resource to keep soils cool and holding moisture in. Just be aware, check to see if it is printed with ink. If it is, you want to be sure it has only black ink. Most black inks are made from soybean oil. Only use the material for paths. Paper and cardboard printed with colored ink is another matter, as this ink may contain some toxic heavy metals.

3. Correction: Newsletter No 1000 : Do You Recall What You Started In April Of 2000 And Are Continuing To This Day? I remember!

“In April of 2011, I gathered information from various Watershed meetings I attended around the state. I listened to the needs, wants and hopes of members of the various watershed groups.” It should have read, In April 2000, I gathered……

4. ADWR Capping Abandoned Water Wells.

Of the 83 reported open wells currently on file, 80 percent have been temporarily capped, permanently capped or safely abandoned. That includes all of the wells that ranked as high priorities because of the hazard they presented. while the number of abandoned wells posing safety hazards are much lower than the number of mines, they are no less of a concern.

5. Oak Creek Cleanup – July 4th Weekend! Join us for a cleanup event with REI Co-Op. This cleanup event won’t be one to miss out on. Join us for coffee and good deeds! Following our hard work, we’ll eat our lunches at Slide Rock State Park where volunteers will receive free entry courtesy of AZ State Parks and will be entered into a raffle courtesy of REI! Be sure to RSVP to this free event at https://www.rei.com/events as space is limited! See below for more info:

We’ll meet at Red Rock High School in Sedona, AZ on Sunday, July 7th, 2019. Arrive as early as 7AM for coffee or plan to arrive by 7:30AM to check-in and fill out volunteer waivers.

Don’t forget to bring a coffee cup! We’ll plan to begin going over the days events just after 7:30AM and will head to Slide Rock State Park (SRSP) shortly after, so be sure to plan to arrive by 7:30AM.

Participants will park at the high school. OCWC and REI will provide transportation to and from Slide Rock State Park (SRSP), including when dispersing to cleanup sites along the canyon.

At SRSP, we’ll go over safety, supplies, and then begin giving this popular 4th of July weekend destination some MUCH needed TLC. Bring smiles, hiking shoes, appropriate warm weather clothing, sunscreen, personal water bottle/coffee cup, and a packable lunch. We’ll have all the cleanup supplies needed, coffee, water, and snacks! There will also be a pretty neat raffle with items generously provided by REI Co-Op!

Invite your friends and family. Again, be sure to register beforehand as space is limited. We really hope to see you there!

Please do not hesitate to contact OCWC Executive Director, Kalai Kollus with any questions at [email protected].

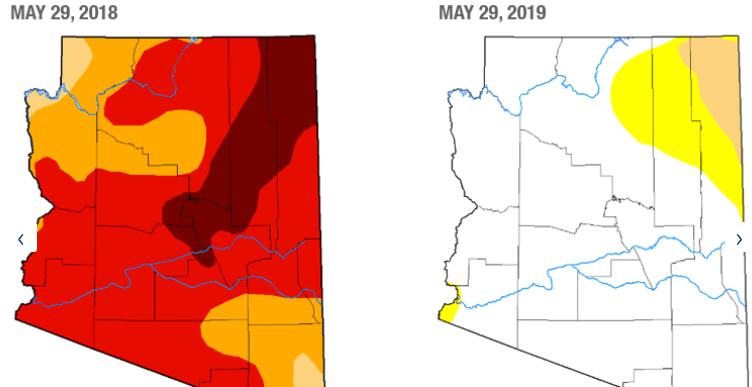

6. Arizona Drought Over? Source: By Melissa Robbins | Cronkite News

PHOENIX – The U.S. Drought Monitor recently reported that, for the first time in its nearly 20-year history, none of the contiguous states was showing symptoms of severe or exceptional drought. That report includes Arizona, as this year’s abnormally wet May helped push the state out of a 10-year drought period.

According to the monitor’s weekly report for late last week, only 20.5% of Arizona was showing moderate drought or “abnormally dry” symptoms. Data for the same week in 2018 found 100% of the state in moderate drought or abnormally dry, with a majority of the state experiencing severe (97%) or extreme drought (73.2%).

Richard Heim, a meteorologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Environmental Information, said the change was tied to this year’s wet spring.

“Rain and snow have been falling in the areas that needed it, so the drought’s contracted a lot,” he said.

Arizona is no stranger to downpours in the monsoon season, which runs June 15 to Sept. 30, according the National Weather Service, but heavy rain and snowfall in spring isn’t typical for the Southwest.

State climatologist Nancy Selover said the increased rain and snow came from winter storms over the Southwest that lingered longer and provided more moisture than in the past.

“Typically, that pattern stops in April, if we even get it,” Selover said. “Last year it was so dry, we never even got that pattern. … So it was really warmer than normal, really drier than normal. This year, we had what I would consider a more normal pattern.

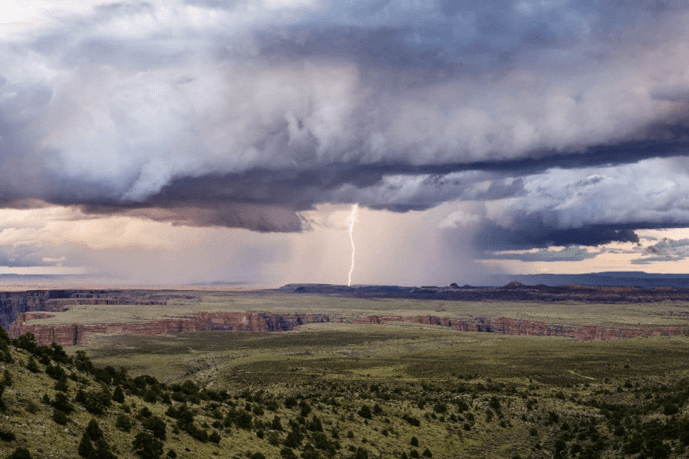

7. Embry-Riddle Meteorology Expects Late Start to Arizona Monsoon Season.

Although June 15 is often referred to by the National Weather Service as the start of the Arizona monsoon season, the meteorology department at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University’s Prescott campus is predicting a delayed start to the annual summer rainy season.

The term monsoon simply means “a seasonal reversal of the wind.” For most of the year, the prevailing winds in Arizona are out of the west, which ushers in the very dry air and very low humidity associated with the desert climate. However, in the summer, the prevailing winds turn to more of a southerly direction, bringing warmer, increasingly humid air. When that humid, buoyant air is heated by the intense desert sun and subject to additional lift by the surrounding mountains, thunderstorms often form during the afternoon hours.

In northern Arizona, monsoon storms typically start around or just prior to the July 4th holiday. But cooler waters currently in the Gulf of California (where most of the moisture needed for these storms originates) will likely delay the start of the Arizona monsoon. Additionally, the ongoing “El Niño” is also known to delay the start of our summer rains.

“The good news for those that love precipitation is that the warmer water southwest of California might support more hurricane activity later in the summer and fall (AugustOctober), so the monsoon might start with a whimper but end with a bang,” said Dr. Mark Sinclair, Professor of Meteorology.

Another factor that may contribute to a slow start to monsoon precipitation is residual late-season snowpack and the moist state of the ground following an unusually wet May. Monsoon precipitation typically commences when mid-level high pressure moves to a location near the Four Corners. To build that high-pressure system, strong solar heating is needed; however heating is reduced when some of the sun’s energy is being used in melting high elevation snow and evaporating moisture rather than warming the atmosphere.

“My best estimate for the onset of monsoon precipitation would be some time after July 10, about a week or two later than normal,” said Sinclair. “This is an educated guess based on past start dates, which have ranged from late June through late July.” Source: Embry-Riddle News.