1. Golf Courses Make Par With Commitment To Water Management. The Phoenix Open has passed. Spring is in the air. And many Valley residents are looking forward to endless rounds of golf. But while you’re on the course, you might wonder about a potential water shortage and how that relates to the gorgeous greens all around you.

Development-Along-Canal-18Valley golf courses are well aware of water conservation issues and work hand in hand with Central Arizona Project to not only caretake their greens, but also our Colorado River supplies. More and more, especially in the desert, golf courses are committed to the sustainable use of water supplies. Examples include:

Upgrading and redesigning irrigation systems

Reducing the need for overseeding

Recycling water

Using less turf and water features

Recently, CAP’s Brian Henning was interviewed by NBC Sports Radio AM 1060 for the Golf Channel, which regularly features information for golf course managers and superintendents. CAP participates a few times a year to give an update on Colorado River supply and operational issues.

CAP will continue to work with the golf industry to update them on the drought and status of the CAP water supply and the Colorado River system and to discuss how the prospect of a shortage will impact Arizona water users, including golf courses.

For now, though, tee off, resting assured that the course you’re on is providing recreational opportunities in a sustainable way. Source: http://www.cap-az.com/public/blog/488-golf-courses-make-par-with-commitment-to-water-management

2. Climate Change Is Shrinking The West’s Water Supply. Three New Studies Show Dry Times Ahead. Picture a snowflake drifting down from a frigid February sky in western Colorado and settling high in the Rocky Mountains. By mid-April, the alpine snowpack is likely at its peak. Warming temperatures in May or June will then melt the snow, sending droplets rushing down a mountain stream or seeping into the soil to replenish an aquifer

The West’s water supply depends on each of these interconnected sources. The frozen reservoir of snow atop mountain peaks, mighty rivers like the Colorado and groundwater reserves deep below the earth’s surface. But the snowpack is becoming less reliable. One of the region’s most important rivers is diminishing and in many places the groundwater level has dropped. Three recent studies illuminate the magnitude of these declines, the role climate change has played and the outlook for the future.

All three studies point to the influence of a warming climate. “Climate change is real, it’s here now, it’s serious and it’s impacting our water supplies in a way that will affect all of us,” says Bradley Udall, a water and climate researcher at Colorado State University. The situation is dire, he says, but reining in greenhouse gas emissions now could help keep the mountains covered with snow and the rivers and aquifers wet.

“The twenty-first century Colorado River hot drought and implications for the future,” Water Resources Research, February/March 2017.

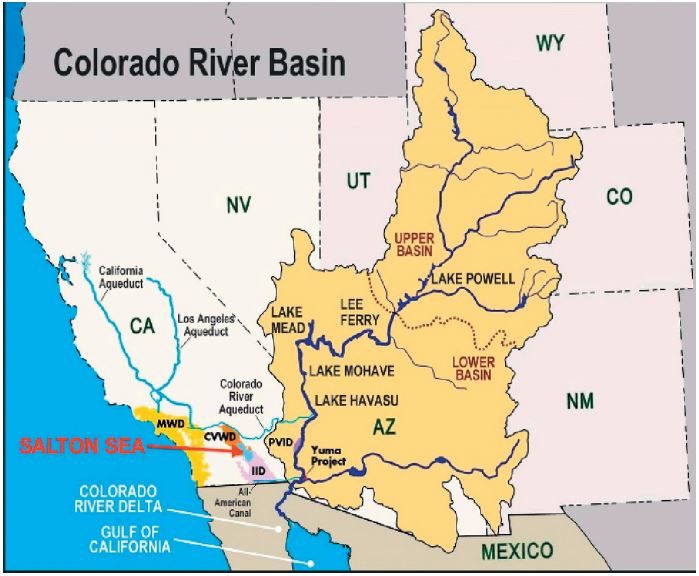

On average, the Colorado River flows were nearly 20 percent lower between 2000 and 2014 compared to the historical norm. Warm weather caused by climate change — not just a lack of precipitation — was the culprit. As the mercury continues to climb, the Colorado could drop by more than half by century’s end

What it means: The Colorado River basin has been in a drought since 2000. Warmer-thannormal temperatures were responsible for about a third of the flow declines. The upper basin is 1.6 degrees Fahrenheit warmer now than during the 1900s, meaning more water is lost to the atmosphere through evaporation from soil, streams and other water bodies. Plants also use more water when it’s hot, partly because the growing season is longer.

Declining flows will further stress the already over-allocated river, which supplies nearly 40 million people in two countries. The authors note that the basin would need a precipitation spike of 4 to 20 percent to counterbalance the flow-reducing effect of future warmer temperatures — “a major and unprecedented change” compared to the past.

Arizona, California and Nevada have been negotiating to reduce their demands on the Colorado, but haven’t agreed on a final plan to address future shortages. “Frankly, that drought contingency plan needs to be put in place just to deal with the river as it is today,” Udall, a study co-author, told the Washington Post. And while the plan will help get the lower basin into balance, it may not be enough to deal with future declines big enough to impact the entire basin, which also includes parts of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming

Climate Change Is Shrinking… Continued

The study: “Large near-term projected snowpack loss over the western United States,” Nature Communications, April 2017.

The takeaway: The West’s mountain snowpack supplies about two-thirds of the region’s water. But it dropped by 10 to 20 percent between the 1980s and 2000s. Within the next three decades, the snowpack could further shrink, by as much as 60 percent.

What it means?

Measurements of the amount of water held within snow from hundreds of stations from Washington to New Mexico revealed the extent of the decline in recent decades. Simulations showed that natural elements alone, like volcanic and solar activity, were not enough to account for the dip. Including factors influenced by humans — like changes in greenhouse gas concentrations — produced models that matched historical reality, implicating climate change as the cause of the snowpack loss.

The study’s predictions for the future range from a drastic drop in snowpack to even a slight gain by 2040. Climate change alone will likely cause a further decrease of about 30 percent, says study co-author John Fyfe, a researcher at Environment and Climate Change Canada. But natural variations in atmospheric conditions above the Pacific could temporarily make the decline worse — or nix it, depending on how they fluctuate. So water managers need to be prepared for both extremes. “It’s a cyclic phenomenon,” Fyfe says. “It’s eventually going to come around and bite you.”

The study: “Depletion and response of deep groundwater to climate-induced pumping variability,” Nature Geoscience, January 2017.

The takeaway: Aquifers have been drawn down in several areas across the country. In parts of California and Nevada, however, groundwater levels have actually risen, perhaps reflecting the success of regulations and recharge projects.

What it means: Aquifer levels declined in about half of the deep groundwater wells monitored nationwide between 1940 and 2015. The lower Mississippi basin, the High Plains over the Ogallala Aquifer, and California’s Central Valley overall have experienced some of the nation’s highest rates of groundwater depletion in recent years. The study found that during dry periods, water users pump more even as natural recharge diminishes, leading to rapid drawdowns in aquifers. Regional studies in Idaho and California reveal a similar pattern of overdraft, particularly during droughts. That can lead to dry wells, land subsidence, ecological damage and other problems.

Sometimes, however, those trends can be reversed. Researchers also found that groundwater levels rose in about 20 percent of the wells, including around Las Vegas and in limited sections of the Central Valley, while the remainder of the wells showed no change. Tess Russo, a hydrologist at Pennsylvania State University and study co-author, cautions that the groundwater level increases could be misleading in places — some wells were monitored for as little as ten years, and if that period happened to be particularly rainy, measurements may not represent an area’s long-term history.

But wet periods and groundwater recharge projects have helped replenish some aquifers. “In many cases, we have plenty of water,” Russo says. Alleviating water stress may be a matter of changing policies and management, including how and where specific crops are grown.

3. How The Colorado River’s Future Depends On The Salton Sea. California’s giant desert lake is key to negotiations over the future of Colorado River water supplies. It’s a battle between millions of water users and a complex and troubled ecosystem.

The drought contingency plan (DCP) is important because, essentially, the Colorado River is over-allocated. Particularly in the lower basin, they have what’s called a structural deficit: In normal years, 1.2 million acrefeet more water flows out of Lake Mead than flows in. So Lake Mead drops by roughly 12 ft per year.

Given that trajectory, it pretty quickly reaches dead pool, meaning there’s no water left in Mead, which then means no water for Southern California and the Central Arizona Project, and 90 percent of the Las Vegas metro area’s water supply dries up. So you’re talking about 30 million people who depend on Lake Mead. Not to mention 1 million acres of irrigated land. And it’s a major hydropower producer.

The DCP is connected to the Salton Sea because the plan expects that Imperial Irrigation District (IID) would take less water from the Colorado River. When Lake Mead drops to elevation 1,045, California is expected to reduce its take from the Colorado River, for the first time, by 200,000 acre-feet. In the most recent DCP terms I saw, Imperial Irrigation District would provide 60 percent of that reduction, so IID would reduce its take of the river by 120,000 acre-feet. IID has certainly stated they need some assurances on the Salton Sea before they move forward on the DCP. They’re a key player. Without IID, California can’t meet its DCP obligations. A 200,000–350,000 acre-foot reduction is counting on IID participation.

Somewhere in the order of 85 percent of the water flowing to the Salton Sea comes from the Imperial Valley. Essentially, it’s surface water and tile drainage from farm fields. As IID takes less water from the Colorado River, that means less water flows to the Salton Sea. Because the Salton Sea is a terminal lake, when less water flows in, the Salton Sea shrinks.

So the concern is that, because of the DCP, the Salton Sea would be smaller than it would be otherwise. As the sea shrinks, some of that land is exposed, and dust blows off that land.

Under existing regulations of the local air district, the landowner is responsible for dust that’s emitted off lands in the Imperial Valley. IID is a major landowner, particularly at the southern end of the Salton Sea, and IID is liable for a lot of the dust getting blown off the Salton Sea. So as the sea shrinks, it represents a direct cost to IID. That’s the crux of it.

Under the Quantification Settlement Agreement (QSA) of 2003 (a water transfer from IID to San Diego), there was an agreement that said as the Salton Sea shrinks, essentially the state of California backstops liability or mitigation requirements.

The QSA parties – Imperial Irrigation District, San Diego County Water Authority and Coachella Valley Water District – have met their responsibility to pay into a mitigation fund. But they capped it because they didn’t know what the total cost would be, although they knew it would be huge. So the state of California said, “We will assume liability for costs that exceed the costs these parties agreed to.”

The state came out [in March] with what they’re calling a “draft 10-year plan for the Salton Sea.” The QSA allowed 15 years to come up with a plan, and it said in the interim we’re going to require IID to deliver mitigation water to offset the impacts of the transfer to San Diego.

But this is the 15th year. So at the end of this year, that requirement goes away. And next year, the Salton Sea is going to start dropping very rapidly because it will no longer get that mitigation water from IID. All of a sudden, it’s going to receive 10–15 percent less water. So, essentially, it’s going over a cliff. IID is seeing this and saying, “Hold on, we need to deal with this problem before we move on to the DCP.”

The state really needed to do this plan five-plus years ago so these projects were being implemented now.

There are two main challenges. One is that it exposes lakebed, which creates dust, and that’s a major public health threat. The Imperial and Coachella valleys already fail to meet air-quality requirements, and asthma rates are already higher than the state average. So, your baseline is an already-bad air-quality situation, which is going to be exacerbated as the Salton Sea shrinks and more dust blows off that lakebed.

The next concern is that as the Salton Sea shrinks, it gets much saltier and other water-quality parameters also decline. Which means that, first, the fish die off. That’s already started to happen. Then a lot of the food sources for the birds die off.

The Salton Sea now is a major stopover for birds on the Pacific Flyway. A total of 424 bird species have been observed on the Salton Sea so far. And of course, in California there are far fewer wetlands than there were historically. We’ve dried up 90–95 percent of the wetlands in California. So these migratory birds have far fewer places to rest and refuel. The Salton Sea has filled that niche. As water quality continues to degrade, it’s no longer going to be able to provide that function. Read more at https://www.newsdeeply. com/water/community/2017/05/16/how-the-colorado-rivers-future-depends-on-the-salton-sea

4. Are You A Spendthrift Or A Skinflint? Take this quiz and determine it for yourself. Feb/Mar “AARP”