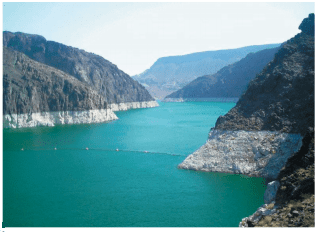

1. Lake Mead Gets Lower, Arizona Prepares For The Worst. Last week, on the border of Nevada and Arizona, Lake Mead set a new record low. The West’s drought is so bad that official plans for water rationing have now begun — with Arizona’s farmers first on the chopping block. Yes, despite the drought’s epicenter in California, it’s Arizona that will bear the brunt of the West’s epic dry spell.

The huge Lake Mead—which used to be the nation’s largest reservoir—serves as the main water storage facility on the Colorado River. Amid one of the worst droughts in millennia, record lows at Lake Mead are becoming an annual event—last year’s low was 7 feet higher than this year’s expected June nadir, 1,073 feet.

If, come Jan. 1, Lake Mead’s level is below 1,075 feet, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which manages the river, will declare an official shortage for the first time ever—setting into motion a series of already agreed-upon mandatory cuts in water outlays, primarily to Arizona. (Nevada and Mexico will also receive smaller cuts.) The latest forecasts give a 33 percent chance of this happening. There’s a greater than 75 percent chance of the same scenario on Jan. 1, 2017. Barring a sudden unexpected end to the drought, official shortage conditions are likely for the indefinite future.

Why Arizona? In exchange for agreeing to be the first in line for rationing when a shortage occurs, Arizona was permitted in the 1960s to build the Central Arizona Project, which diverts Colorado River water 336 miles over 3,000 feet of mountain ranges all the way to Tucson. It’s the longest and costliest aqueduct in American history, and Arizona couldn’t exist in its modern state without it. Now that a shortage is imminent, another fundamental change in the status quo is on the way. As in California, the current drought may take a considerable and lasting toll on Arizona, especially for the state’s farmers.

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 1

According to Robert Glennon, a water policy expert at the University of Arizona, the current situation was inevitable. “It’s really no surprise that this day was coming, for the simple reason that the Colorado River is overallocated,” Glennon told me over the phone last week.

“A call on the river will be significant,” Joe Sigg, director of government relations for Arizona Farm Bureau, told the Arizona Daily Star. “It will be a complete change in a farmer’s business model.” A “call” refers to the mandatory cutbacks in water deliveries for certain low-priority users of the Colorado. Arizona law prioritizes cities, industry, and tribal interests above agriculture, so farmers will see the biggest cuts. And those who are lucky enough to keep their water will pay more for it.

Glennon explained that the original Colorado River compact of 1922, which governs how seven states and Mexico use the river, was negotiated during “the wettest 10-year period in the last 1,000 years.” That law portioned out about 25 percent more water than regularly flows, so even in “normal” years, big reservoirs like Lake Mead are in a long-term decline. “We’ve been saved from the disaster because Arizona and these other states were not using all their water,” Glennon said.

They are now. Since around 2000, Arizona has been withdrawing its full allotment from the Colorado River, and it’s impossible to overstate how important the Colorado has become to the state. About 40 percent of Arizona’s water comes from the Colorado, and state officials partially attribute a nearly 20-fold increase in the state’s economy over the last 50 years to increased access to the river.

On April 22, Arizona held a public meeting to prepare for an eventual shortage declaration, which could come as soon as this August. The latest rules that govern a shortage, established in 2007 by an agreement among the states, say that Arizona will have to contend with a 20 percent cut in water in 2016 should Lake Mead fall below 1,075 feet, which will decrease the amount available to central Arizona’s farmers by about half. At 1,050 feet, central Arizona’s farmers will take a three-quarters cut in water. At 1,025 feet, agriculture would have to make due largely without water from the Colorado River. That would probably require at least a temporary end to large-scale farming in central Arizona. Below 1,025 feet, the only thing Colorado River states have agreed to so far is a further round of negotiations. In that emergency scenario, no one really knows what might happen.

Beyond Arizona, the implications of the ongoing megadrought in the West are profound. The Colorado River currently supplies water to more than 40 million people from Denver to Los Angeles (as well as Las Vegas, Phoenix, Tucson, San Diego, Salt Lake City, Albuquerque, and Santa Fe—none of which lie directly on the river). According to one recent study, 16 million jobs and $1.4 trillion in annual economic activity across the West depend on the Colorado. As the river dries up, farmers and cities have turned to pumping groundwater. In just the last 10 years, the Colorado Basin has lost 15.6 cubic miles of subsurface freshwater, an amount researchers called “shocking.” Once an official shortage is declared, Arizona farmers will increase their rate of pumping even further, to blunt the effect of an anticipated sharp cutback.

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 2

According to Dan Bunk of the Bureau of Reclamation’s Colorado River operations office, the current projections, factoring in both the ongoing drought and the systemic overallocation, are “almost guaranteeing a shortage in 2017.” Engineers are already installing new hydropower electricity-generating equipment at Lake Mead to prepare for the contingency of the lake reaching so-called “dead pool” levels—below which the Colorado River will no longer be able to spin Hoover’s power-generating turbines. A new intake from Lake Mead to Las Vegas will come online later this year, allowing the city to essentially suck the lake dry, all the way down to the last drop.

According to Robert Glennon, a water policy expert at the University of Arizona, the current situation was inevitable. “It’s really no surprise that this day was coming, for the simple reason that the Colorado River is overallocated,” Glennon told me over the phone last week.

So is there anything that can be done? As is the case in California, the fate of the Colorado River is largely in the hands of agriculture. Nearly 80 percent of the river’s annual flow is diverted for agricultural use. Since urban water use is becoming more efficient at a quicker pace than agricultural water use, the only way to make the numbers work in an increasingly climate-constrained future is to switch to less waterintensive crops or decrease the total acreage devoted to agriculture. And that’s not happening fast enough.

Among the other options officially on the table in the state of Arizona: desalination and cloud seeding. But, according to Glennon, such proposals are “not responsible stewardship of the state water agency.” (The desalination idea would require building a desalination plant in Mexico and constructing another Central Arizona Project–like aqueduct system to transport it northward across the border.) Glennon thinks the answer is much easier. “We need to stop growing alfalfa in the deserts in the summertime.” And what if nothing changes? Well, then, the water supply certainly will. “Pretty dramatic cutbacks could happen relatively quickly,” Glennon said. “That will bring a new urgency to doing a lot of things.” Source: Slate

2. Self-Guided Tours Available Via Smartphone At Sweetwater Wetlands (VIDEO) – Tucson Water and Arizona Project WET have partnered to provide a series of self-guided tours at the Sweetwater Wetlands. The new Discovery Program engages visitors through a journey along the path that surrounds the ponds and recharge basins. Guests can use a QR code reader app on any smart device to view the Wetlands in a scientific way as they navigate around the 60-acre site. Sweetwater Wetlands is part of Tucson Water’s reclaimed water system, where treated wastewater is filtered through recharge basins, replenishing the local aquifer. The reclaimed wastewater is then distributed for reuse at Tucson’s golf courses, parks, and schools. In addition, the Wetlands is an urban wildlife habitat that the public can visit seven days a week. Follow the Tucson 12 video link below to see what the tour is all about. video: http://bit.ly/1diAdP1 Sweetwater Wetlands: http://1.usa.gov/1mGlElO

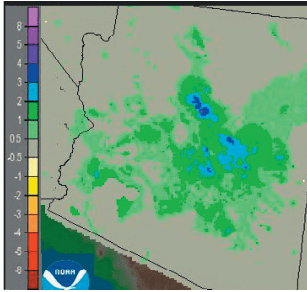

3. Climate of Arizona. Precipitation: In the past 30 days, much of central Arizona recorded well above-average precipitation. Climatologically, this is one of the drier times of year for the Southwest, so any substantive precipitation during this timeframe is generally unexpected but welcome, as it helps tamp down fire risk. Water year observations since October 1 demonstrate the persistent and ongoing drought, with most western states, including Arizona, recording large areas of below-average to well below-average precipitation. Left: Departure from Normal Precipitation – Past 30 days.

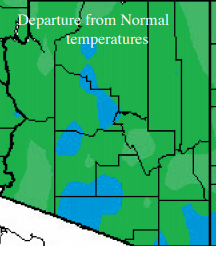

Temperature: Lingering storms and above-average humidity contributed to mild and pleasant conditions across the Southwest, with temperature anomalies in Arizona between 2 and 6 degrees below average across the region in the past 30 days. This counters more than six months of record or near-record warm average temperatures that have persisted in the Southwest and the western U.S. since the water year began on October 1.

Wildfire: Mild spring weather, above-average precipitation, and relative humidity have resulted in reduced wildfire risk in Arizona so far this season. The 2014 tropical storm season contributed to abundant fine fuels, which can escalate wildfire risk when the region eventually dries out. An early or even on-time start to the monsoon could limit the window of highest wildfire risk, but a delayed start could extend it, especially given the dry lightning associated with summer storms.

Precipitation & Temperature Forecasts: The May 21 NOAA-Climate Prediction Center seasonal outlook predicts above-average precipitation this spring into summer for much of the Southwest and Intermountain West, although California and most of Arizona are notable exceptions. Temperature forecasts remain split across the region, with elevated chances for above-average temperatures along the West Coast and eastward into Arizona (and most of the western U.S.), and increased chances for below-average temperatures in western Texas and into eastern New Mexico.

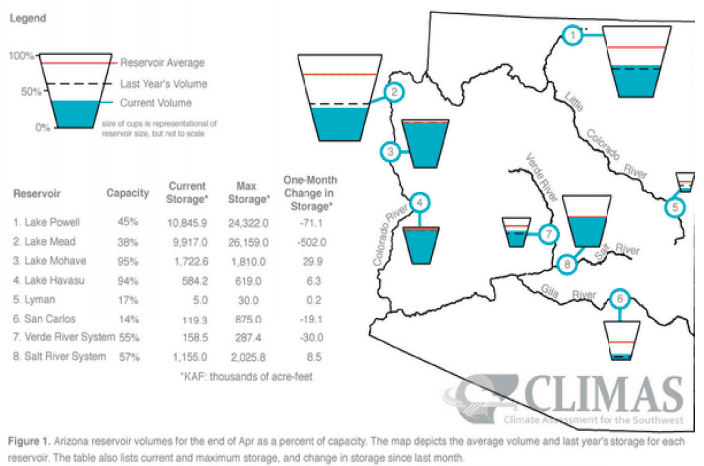

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 4 Drought & Water Supply: The U.S. Drought Monitor highlights persistent drought conditions across the West, with particularly severe conditions in California and Nevada, and emphasizes primarily long-term drought conditions across most of Arizona and much of New Mexico. Total reservoir storage was 44 percent in Arizona and 26 percent in New Mexico. Below-average snowpack and above-average temperatures have resulted in earlier-than-normal melt-out in numerous areas and losses associated with sublimation and infiltration.

4. University of Arizona Survey found that more than 70 percent of Arizonans support government action to reduce global warming, and a majority of state residents believe people are at least partly to blame for the planet’s warmer temperatures. The survey also found more than half of Arizonans believe global warming has caused more droughts and storms around the world, and more forest fires and heatwaves in the state.

The survey of 803 adult Arizona residents was conducted by telephone in November and December 2014 by the independent polling company Abt SRBI to better understand Arizonans’ views on climate change and how those views vary depending on age, gender, ethnicity and political affiliation.

Source:http://uanews.org/story/ua-poll-arizonans-concerned-about-global-warming

5. Celebrating Memorial Day. Monday, May 25, people around the United States will celebrate Memorial Day as a day. Memorial Day, originally called Decoration Day, is a day of remembrance for those who have died in service of the United States of America. Over two dozen cities and towns claim to be the birthplace of Memorial Day. While Waterloo N.Y. was officially declared the birthplace of Memorial Day by President Lyndon Johnson in May 1966, it’s difficult to prove conclusively the origins of the day.

Regardless of the exact date or location of its origins, one thing is clear – Memorial Day was borne out of the Civil War and a desire to honor our dead. It was officially proclaimed on 5 May 1868 by General John Logan, national commander of the Grand Army of the Republic, in his General Order No. 11. “The 30th of May, 1868, is designated for the purpose of strewing with flowers, or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village and hamlet churchyard in the land,” he proclaimed. The date of Decoration Day, as he called it, was chosen because it wasn’t the anniversary of any particular battle.

On the first Decoration Day, General James Garfield made a speech at Arlington National Cemetery, and 5,000 participants decorated the graves of the 20,000 Union and Confederate soldiers buried there.

The first state to officially recognize the holiday was New York in 1873. By 1890 it was recognized by all of the northern states. The South refused to acknowledge the day, honoring their dead on separate days until after World War I (when the holiday changed from honoring just those who died fighting in the Civil War to honoring Americans who died fighting in any war).

It is now observed in almost every state on the last Monday in May with Congressional passage of the National Holiday Act of 1971 (P.L. 90 – 363). This helped ensure a three day weekend for Federal holidays, though several southern states have an additional separate day for honoring the Confederate war dead: January 19th in Texas; April 26th in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Mississippi; May 10th in South Carolina; and June 3rd (Jefferson Davis’ birthday) in Louisiana and Tennessee.

The practice of decorating soldiers’ graves with flowers is an ancient custom. Soldiers’ graves were decorated in the U.S. before and during the American Civil War. A claim was made in 1906 that the first Civil War soldier’s grave ever decorated was in Warrenton, Virginia, on June 3, 1861, implying the first Memorial Day occurred there. Though not for Union soldiers, there is authentic documentation that women in Savannah, Georgia, decorated Confederate soldiers’ graves in 1862. In 1863, the cemetery dedication at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, was a ceremony of commemoration at the graves of dead soldiers. Local historians in Boalsburg, Pennsylvania, claim that ladies there decorated soldiers’ graves on July 4, 1864. As a result, Boalsburg promotes itself as the birthplace of Memorial Day

Following President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865, there were a variety of events of commemoration. The sheer number of soldiers of both sides who died in the Civil War, more than 600,000, meant that burial and memorialization took on new cultural significance. Under the leadership of women during the war, an increasingly formal practice of decorating graves had taken shape. In 1865, the federal government began creating national military cemeteries for the Union war dead.

Nearly 10,000 people, mostly freedmen, gathered on May 1 to commemorate the war dead. Involved were about 3,000 school children, newly enrolled in freedmen’s schools, as well as mutual aid societies, Union troops, black ministers and white northern missionaries. Most brought flowers to lay on the burial field. Today the site is remembrance celebration would come to be called the “First Decoration Day” in the North. Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memorial_Day P