Daniel Salzler No. 1289

EnviroInsight.org Three Items January 17, 2025

—————Feel Free To Pass This Along To Others——————

If your watershed is doing something you would like others to know about, or you know

of something others can benefit from, let me know and I will place it in this Information .

If you want to be removed from the distribution list, please let me know.

Please note that all meetings listed are open.

Enhance your viewing by downloading the pdf file to view photos, etc.

The attached is all about improving life in the watershed through knowledge.

If you want to be removed from the distribution list,

please let me know. Please note that all meetings listed are open.

Check our website at EnviroInsight.org

1. Trees: Why You Should Have Some In Your Yard. Trees do a lot of good for you and your community and in your yard, regardless of why it was planted. Here’s why trees are beneficial.

• Cooling Shade: The canopy of your tree helps to lower near by temperatures by as much as 10 degrees F, shielding us all from the dangers of urban heat island effect.

• Cleaner Air: Leaves filter airborne pollutants to improve the quality of air we breathe.

• Rainwater Management: A mature tree can intercept 1,000 gallons of rainwater per year, a critical function in preventing floods.

• Wildlife biota: Your trees provide food and shelter for a wide range of wildlife, including birds, pollinators and small animals.

• Community Well-Being: The presence of trees improves mental health and promotes physical activity.

Source: arboretum.com

2. Conservation Agreement Will Protect Upper Verde River, Grasslands And A Historic Ranch. Source: John Leos, Arizona Republic.

PAULDEN — Standing on the edge of the Big Chino Valley, it’s impossible to see the end of the grasslands that stretch for miles into the horizon. Herds of cattle and wild pronghorn antelope graze together in this remote expanse, unbroken except for the stray dirt roads crisscrossing between ranches. Below the surface, a huge groundwater resource flows into the nearby springs that feed the headwaters of the Verde River.

In this vast landscape, ranchers and conservationists are working together to guard against overdevelopment and preserve ranching in Yavapai County.

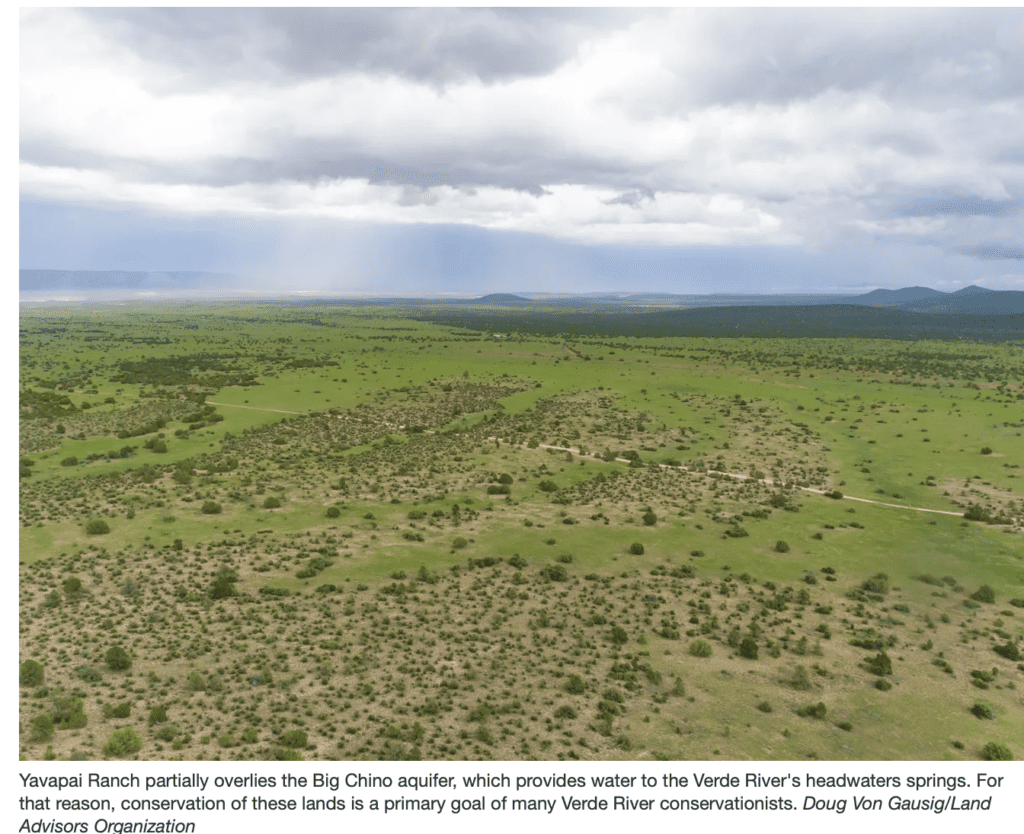

A historic conservation easement closed in the Big Chino Valley last month, marking the first step in a broad $23 million conservation strategy seeking to preserve critical grasslands habitat and protect the aquifer feeding the Upper Verde River.

Covering 1,889 acres, the easement on the Yavapai Ranch property emerged from a partnership with the Nature Conservancy and the Natural Resources Conservation Service, an agency of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Other funding partners include the Central Arizona Land Trust, Salt River Project and Arizona Game and Fish Department.

“Conservation easements are a great tool for land use planning where we don’t have other mechanisms to do so, such as zoning. And especially in the rural landscapes of Arizona,” said Heather Reading, a conservation advisor for Land Advisors Organization, who represented Yavapai Ranch in the easement negotiations. “It compensates the landowners at fair market value for the property rights that they’re

A conservation easement is a voluntary legal agreement between a private landowner and a qualified organization that limits the development of private land for environmental conservation. With ongoing annual monitoring, the agreement can be tailored to meet the individual needs of the landowner while

Clamming for Asiatic clams then Verde River in AZ. Cambodians in AZ recreate family traditions by clamming for Asiatic clams in the Verde River and cooking on the shore.

Conservation easements have become an effective tool for conserving land in rural Arizona because they exist in perpetuity. This means that even if the property changes hands, the conservation agreement will always remain in effect and the landscape will be protected.

Without the protection, conservationists warn that the sprawling grasslands could be cut into pieces by unchecked overdevelopment, and landowners risk the possibility of state groundwater regulation.

Desert rivers:Why river advocates say Arizona’s upper Verde should earn ‘Wild and Scenic’ protections

Protecting the Upper Verde River

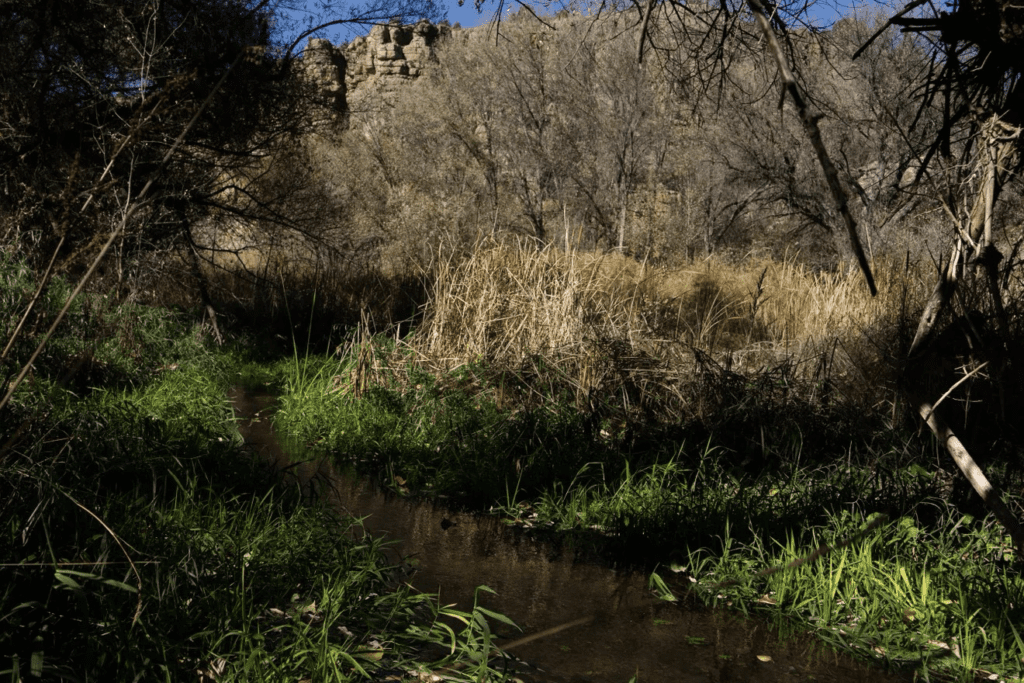

In the shadow of Little Thumb Butte, the perennial springs flowing from the canyons form the headwaters of the Verde River. These winding waterways provide an oasis for wetland wildlife like the southwest river otter. Trees and grasses burst from the creek beds to support the diverse native fish below and migratory birds above.

The Big Chino Aquifer provides the majority of the baseflow for the first 25 miles of the Verde River. The nearby communities of Prescott, Prescott Valley and Chino Valley pump groundwater

from an aquifer that also contributes to the river, which goes on to provide drinking water for metropolitan Phoenix farther downstream.

Conservationists and land managers are working to prevent development-driven aquifer depletion like the kind that occurred in the Kingman area of Mojave County last year. After an expansion of large-scale irrigated farming in the region threatened the aquifer, the Arizona Department of Water Resources stopped further development and placed the region under increased regulation to prevent the collapse of the Hualapai Basin.

The Big Chino Aquifer is located outside an Active Management Area, meaning there are currently no governmental restrictions to groundwater withdrawals. Conservation easements provide an alternative to state-mandated regulation by allowing private landowners to limit groundwater withdrawals on their property.

“We recognize that in rural Arizona, we have challenges for groundwater management,” said Reading. “So the conservation easement program is very much a community-driven and locally-led solution to those challenges, and that is providing an alternative, that’s a voluntary alternative.”

With limited options for conserving private land, conservation easements are the only tool being used by the Nature Conservancy and its partners to preserve the groundwater that feeds the Upper Verde River.

Riparian areas:The invasive Arundo reed threatens Arizona rivers. Why getting rid of it is so difficult

Preserving the Big Chino Grasslands

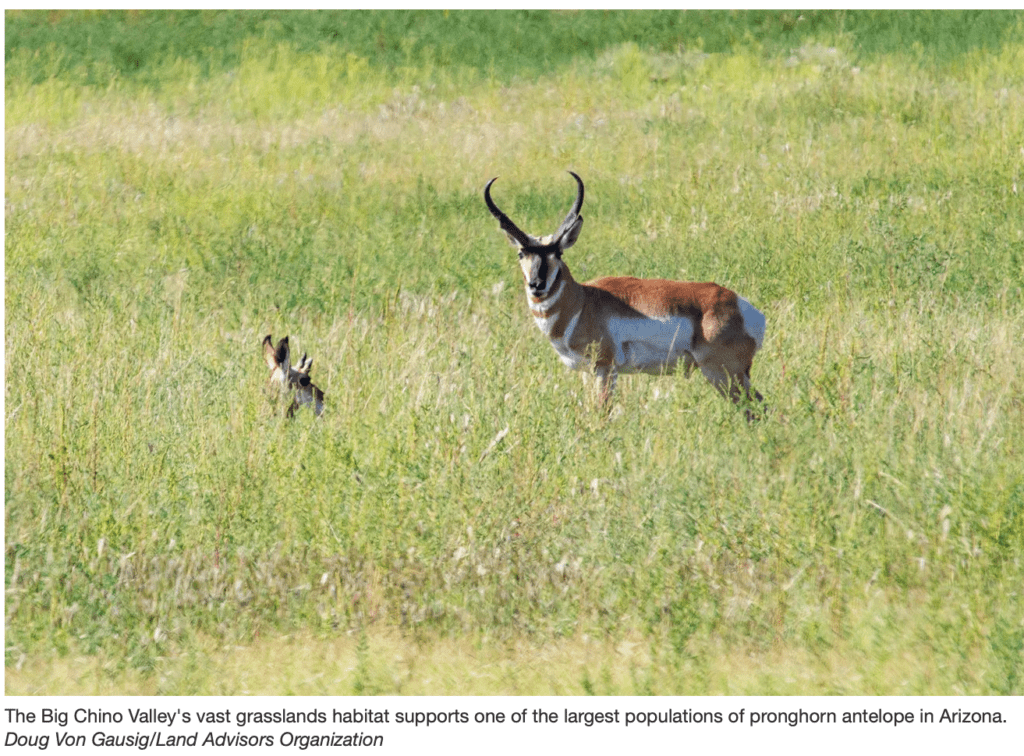

Hidden within the sea of native grass, prairie dogs pop in and out of their burrows catching glimpses of a red tail hawk circling in the distance. Biodiversity abounds in the Big Chino Valley, which has been designated as a “Grasslands of Special Significance” by the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

The high-quality habitat supports one of the largest herds of pronghorn antelope in Arizona, as well as nesting for western burrowing owls and a potential reintroduction site for the endangered black-footed ferret.

The valley is also a part of the Grand Canyon to Prescott Wildlife Corridor identified by the Arizona Game and Fish Department as a key migratory path for wildlife across the landscape.

“One of the reasons that we selected this habitat to protect, of course, is supporting the really important wildlife linkage,” said Jody Norris, protection program director at the Nature Conservancy, “It’s important to keep the fragmentation to limited so that these species are able to to move to the grassland habitat.”

Keeping the ranch alive

The crumbling stone buildings that dot the valley are a reminder of the area’s notable history, and the ranchers and farmers who work on the land are sticking to tradition in the face of evolving development across the county.

Homesteaded in 1868, the Yavapai Ranch is one of the oldest cattle ranching operations in the state, and the conservation easement is designed with that legacy in mind. The agreement ensures that the ranch can continue its current operations, while receiving a financial benefit from selling the development rights to the property.

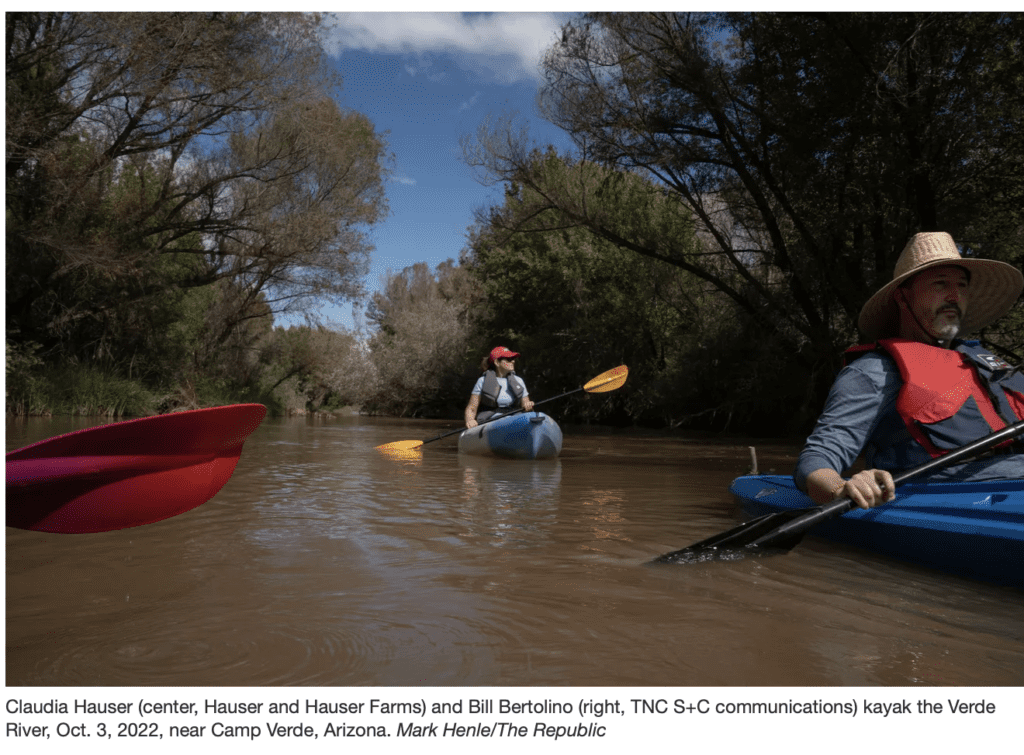

Downstream in Camp Verde, Kevin Hauser and his family were able to pay off the mortgage on their property and reinvest into the farming operations at Hauser and Hauser Farms after partnering with the Nature Conservancy on a conservation easement.

More than a financial advantage, Claudia Hauser described the easements on the family farms as a fulfillment of her late husband’s mission to “protect the land.” Kevin Hauser died in 2019, but his values as a farmer and conservationist live on with his wife and son.

“When Kevin and I were married, we leased the farmland for so long there was so much pressure from development and realtors. But now that it’s our family’s, I don’t feel that pressure anymore,” said Claudia Hauser, “It’s such a relief to be able to know that my family is going to continue to farm this land and continue that legacy of our forever farm.”

3. Alternative Crops Offer Hopes For The Colorado River. Source: The Nature Conservancy Decemberc1, 2024

It’s nearly dusk as Hunter Doyle checks his last field. He’s walking slowly, chest-deep among rows of dark green crops on a farm in the picturesque Rocky Mountain high country near the town of Kremmling, Colorado. He likes what he sees. “It’s just beautiful,” he says. “We only watered this once but look how high it’s jumped up.”

Doyle, who is the Intermountain Agronomy Specialist for The Land Institute, is monitoring a test field of Kernza®, a perennial crop that’s generating buzz among farmers and ranchers throughout the West. As climate change grips the region, alternatives like Kernza® offer a tantalizing hope: a crop with the potential to deliver economic returns, withstand drought and use less water.

HUNTER DOYLE Doyle is the Intermountain Agronomy Specialist Doyle with the Land Institute. © Doyle

BENEFITS OF KERNZA Kernza roots grow 10 feet deep, benefitting soil structure and preventing erosion. © Hunter Doyle

“People know we have to change,” Doyle says, “but they need realistic options that will work on a big scale in their fields.” Delivering those options—and proof of their viability—is the goal of the Intermountain West Alternative Forages Research Project, which funds Doyle’s work. The project is run by a suite of partners—including The Land Institute, The Nature Conservancy, Colorado State University, Trout Unlimited, American Rivers and Reeder Creek Ranch.

At sites throughout the Upper Colorado River Basin, this team is analyzing the large-scale growth potential of more water-friendly forage crops, or crops used for cattle feed. Their findings—and a widespread shift to crops that use less of the Colorado River—could be a game changer for a system teetering on the brink of disaster.

A Reckoning for the River—And All of Us

“This isn’t just about farmers and ranchers,” says Aaron Derwingson, who’s working with Doyle on the Alternative Forage Project and manages water work for The Nature Conservancy’s Colorado River Program.

Seeds of Change

Alternative crops might offer one refreshingly straightforward and impactful solution. “When you look at water consumption,” Derwingson explains, “traditional forage crops are an opportunity for innovation.” According to a recent study published in Communications Earth & Environment, nearly half of the water drawn from the Colorado River is being used to irrigate crops like alfalfa and grass hay to feed beef and dairy cattle—supplying meat, milk, cheese, yogurt and more to millions of us. It’s easy to see why alfalfa has been prized by western agricultural producers for more than a century: it’s nutritious, it tolerates many different climates and it has a high yield. These qualities, Derwingson notes, are what we need to find in a less thirsty crop. And there are already promising contenders.

ALFALFA Nearly half of the water drawn from the Colorado River is being used to irrigate crops like alfalfa and grass hay to feed beef and dairy cattle. © Uche Iroegbu

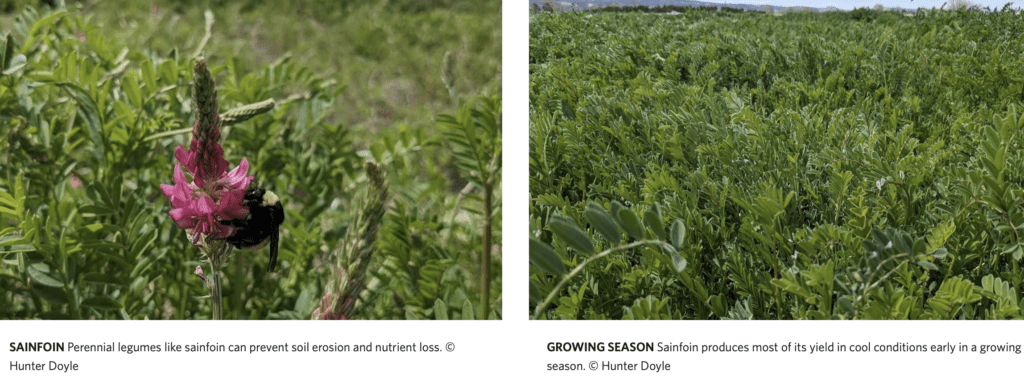

Kernza®, which is a perennial intermediate wheatgrass, and sainfoin, which is a legume, both have the potential to use substantially less water than alfalfa, yet they are still nutrient-rich and offer a high yield. Developed and studied by The Land Institute, Kernza® and sainfoin have also already been used by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Conservation Reserve Program for improving natural resource management. All good signs, Derwingson points out, but key questions remain—especially around the practical, large-scale growth of these alternative crops in the Colorado River Basin, where drought and heat are intensifying. That’s why new, collaborative research in this region is vital.

The Intermountain West Alternative Forages Research project team is now running field tests at seven farms and two research stations in western Colorado, southeast Utah and southwest New Mexico. They’re raising and monitoring fields of Kernza® and sainfoin to determine whether these crops can effectively be grown in a variety of climates and field conditions in the Upper Colorado Basin while providing more drought resilience. Now entering their second year of research, the team is assembling a suite of comprehensive baseline data to understand how much water Kernza® and sainfoin require in each location. Those are revealing numbers they can compare against the water-saving potential of other alternative crops or solutions proposed for the Colorado River Basin.

The Real Test: Rancher Buy-In

Doyle, who spends his long days driving between

test plots of Kernza® and sainfoin in western Colorado—from Cortez to Steamboat—stresses there’s a lot more to his work than water and crop data collection. “A lot of my job is outreach and building relationships in these rural communities,” he says. “The ranchers are excited and curious, and some are also skeptical. They’re business owners and they want to adapt and use less water, but they can’t afford to fail.”

Doyle says that’s the beauty of the Alternative Forages project. “I tell ag producers: let us take the risk, and let us struggle and learn out here, and then we can tell you what’s really possible in your own fields.” Derwingson underlines this point: “We want to assess the reality of whether farmers and ranchers in the Upper Colorado Basin would or could actually switch to these crops.” To that end, the research team’s seven test sites include Doyle’s fields as well as the fields of several farmers and ranchers in western Colorado who have volunteered to help with the research. Traditionally alfalfa and grass hay growers, these producers have now planted Kernza® and sainfoin, and they are gathering real-world experience on switching to these alternative crops, including best practices and pitfalls to avoid.

One farmer who volunteered to join the project is Paul Bruchez, who raises cattle with his father and brother on a ranch near Kremmling and irrigates with water from the Colorado mainstem and small tributaries. “My family’s been in agriculture for five generations. We’re very proud food growers,” he says. “When we started this Kremmling operation in 2000, we thought it would be bliss. Instead, by 2002, we started to see very different flows on the river—drought conditions that impacted our family in a number of ways. We knew we needed to be better prepared.”

Copyright 2025 EmviroInsight.org