Daniel Salzler No. 1280 EnviroInsight.org Three Items November 15, 2024

—————Feel Free To Pass This Along To Others——————

If your watershed is doing something you would like others to know about, or you know

of something others can benefit from, let me know and I will place it in this Information .

If you want to be removed from the distribution list, please let me know.

Please note that all meetings listed are open.

Enhance your viewing by downloading the pdf file to view photos, etc.

The attached is all about improving life in the watershed through knowledge.

If you want to be removed from the distribution list,

please let me know. Please note that all meetings listed are open.

Check our website at EnviroInsight.org

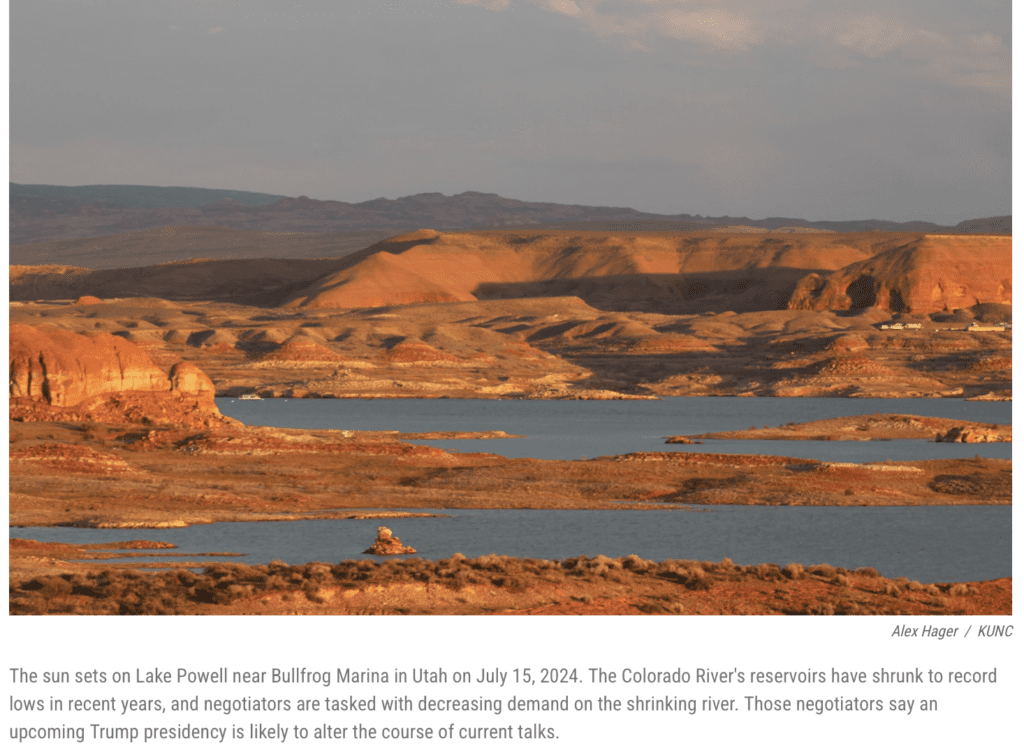

1. How Will A Second Trump Presidency Shape The Colorado River?

KUNC | By Alex Hager

The people who will determine the future of the Colorado River said they do not anticipate major changes to their negotiation process as a result of former president Donald Trump’s return to the White House.

Multiple officials from states that use the Colorado River pointed to historical precedent and said that similar negotiations in the past were largely unaffected by turnover in presidential administrations. Historically, state leaders have written the particulars of river management rules, and the federal Bureau of Reclamation implements the states’ ideas.

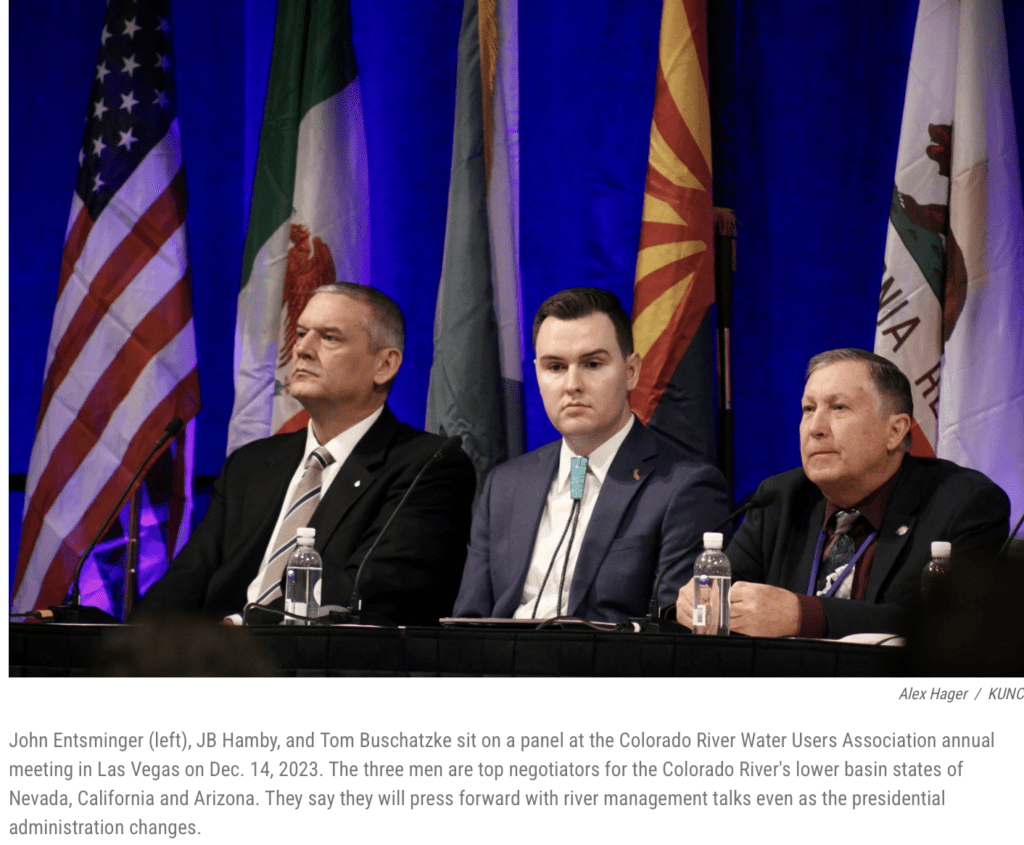

“I think if you’re using history as your guide, the election probably doesn’t mean a whole lot,” said John Entsminger, Nevada’s top water negotiator. “We have seen both Democratic and Republican administrations over the last two and a half decades have pretty consistent Colorado River policy.”

The Colorado River is used by 40 million people from Wyoming to Mexico. Climate change is shrinking its supplies, and policymakers are trying to agree on ways to rein in demand. They are under pressure to come up with a new set of rules for sharing its water by 2026 when the current guidelines expire.

Those policymakers – a group of seven appointed officials from each of the states that use the Colorado River – are split into two factions. Those two groups released competing proposals for how to manage the river after 2026, and they do not appear close to an agreement.

The Biden Administration had urged those states to coalesce around one proposal before the presidential election to help ensure it could go through the necessary paperwork and be implemented smoothly, but state leaders failed to do that.

On the campaign trail, Trump suggested major shakeups to the federal government, suggesting that he would gut or dissolve some federal agencies entirely. Entsminger said he does not think those efforts will extend to the federal agencies that help manage water in the West.

“I expect there to be a Department of the Interior,” he said. “I expect there to be a Bureau of Reclamation because someone has to actually operate the dams on the Colorado River.”

However, the Trump Administration may not be in a hurry to appoint new heads of those agencies. Entsminger pointed to past administrations that have prioritized other agencies, and Interior Department leaders haven’t been appointed until eight or nine months after inauguration day.

“The basin states can’t afford to sit around and wait to hear who that’s going to be,” Entsminger said. “It’s incumbent upon the basin states to keep working towards a solution in the interim, until we know who the new administration’s representatives are going to be.”

Scientists and policymakers broadly agree that climate change is driving the two-decade megadrought that is shrinking the Colorado River, but Trump has denied that climate change even exists. His administration appears poised to expand fossil fuel extraction, which would accelerate climate change. Western water leaders don’t expect those attitudes to get in the way of finding ways to rein in water demand.

“I don’t think that the debate over climate change is going to change the view of the federal administration about the need to deal with a smaller river, or how we’re going to get there,” said Tom Buschatzke, Arizona’s top water negotiator. “I just don’t see it happening.”

Even if Colorado River management at the federal level is stable, discord between the states could make things tricky. Currently, the Upper Basin states of Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico are in disagreement with their Lower Basin neighbors – California, Arizona and Nevada. The two camps have a rivalry going back more than a century, and it still divides them today.

Elizabeth Koebele, who researches water policy at the University of Nevada, Reno, said that creates a risky level of instability.

“I worry that when our house isn’t in order inside the [Colorado River] basin,” she said, “Then these bigger, national level, ‘big-P Political’ changes are more likely to impact policy making, or more likely to add more stress to policy making.”

Koebele said federal leaders have often helped spur action and agreement among states by giving them “ultimatums” and deadlines to submit water management plans. The federal water officials appointed by Trump, she said, will face a tall order if they want to do that this time around.

“The stakes are probably higher than ever,” Koebele said, “And the Upper Basin and Lower Basin are facing major conflicts about who’s responsible for doing something about this. So I’m maybe not as optimistic as the state [negotiators] are.”

State water negotiators in both basins said they plan to keep pressing forward, and seemed optimistic about agreement, even amid shifting politics at the national level.

“We’re committed to coming up with a solution,” said Gene Shawcroft, Utah’s top negotiator. “This is a seven state solution, not an administration solution, if you will. And so there’s no waffling in our commitment to come up with a solution.”

Shawcroft said he believes any plan agreed upon by all seven states would be accepted by a future Trump administration.

This story is part of ongoing coverage of the Colorado River, produced by KUNC and supported by the Walton Family Foundation. KUNC is solely responsible for its editorial coverage.

2. What The Data Says About Arizona’s 2024 Water Year. KJZZ | By Mark BrodiePublished November 5, 2024 at 11:46 AM MST

The 2024 water year saw lower than normal precipitation across Arizona, and the hottest summer on record here. Those facts are perhaps not surprising. But, what might be a bit unexpected is that drought conditions in Arizona were a little better at the beginning of this October than at the same time last year.

Mike Crimmins, an extension specialist and climatologist with the University of Arizona Cooperative Extension, contributed to the Water Year Report from the National Integrated Drought Information System and joined The Show to talk about what it says and some of his key takeaways.

Full conversation

MARK BRODI024 water year saw lower than normal precipitation across Arizona and the hottest summer on record here. Those facts are perhaps not surprising, but what might be a little unexpected is that drought conditions in Arizona were a little better at the beginning of this October than at the same time last year.

Mike Crimmins is an extension specialist and climatologist

with the University of Arizona Cooperative Extension.

He contributed to the water year report from the National Integrated Drought Information System and joins me to talk about what it says and Mike, what to you are some of the key takeaways here?

MIKE CRIMMINS: The interesting thing is that we’re, this report came out right in the middle of the just string of record heat at the end of a early retreating monsoon. So we were baking with these record temperatures hadn’t rained much, especially in Phoenix over the course of the monsoon season and that kind of retreated early.

But the whole this report was detailing the water year. And so the water year is actually this period of time from October of the previous year through September 30th.

And so that water year, which is really tuned up to try to catch the winter as a whole in the middle was actually quite interesting for the southwest and I think we forgot that it was actually quite wet and cool last winter and into last spring. And so if you put all that together in a water year report, you get this interesting mix of cool and wet conditions followed by a somewhat miserable summer at the tail end of the water year.

BRODIE: Well, yeah, I mean, sort of to that point, you mentioned the report mentions that Arizona experienced its hottest summer on record which spans about 130 years. But then when you look at the actual map with the, you know, the increasingly, you know, dark shades of red indicating drought. The map from October 1st of this year looked a lot less dark red than the map from October 3rd of last year.

CRIMMINS: I know we’ve been kind of hitting the guard rails over the last couple of years and we can even go back to the really miserable summer of 2020 when we broke all the records as far as no monsoon precipitation across much of the state. And then since then, we’ve been kind of cycling between, we had two La Nina winters. La Nina winters typically give us drier than average conditions in the southwest.

One of those did the second, winter of La Nina actually gave us wet conditions and then we ended up having a quite dry monsoon last year of 2023. It was actually below average. Much of the state broke a bunch of temperature records at that point.

And then we actually had an El Nino event which typically gives us above average precipitation for the southwest come online last fall and it actually delivered, we, we ended up having a pretty good, winter, cool temperatures down a bit and brought us some decent precipitation.

And then of course, we can’t, you know, have a, you can’t enjoy that for too long. We went into this monsoon season and then pretty mediocre precipitation. Some parts of the state did, ok, came in an average, some real small areas had above average precipitation.

But I think as you know, in Phoenix, was not so great and so kind of the middle part of the state up into the eastern part of the state, parts of the southeast part of the state just really fell behind and then the heat, just set in and just would, it’s still kind of holding on to us right now.

BRODIE: Right. Well, and as far as water goes, the report notes that Lakes Mead and Powell are still pretty far below where they ought to be.

CRIMMINS: Yeah, I mean, and those, the reservoirs operate on much, much longer time scales, you know, so we’re hitting the guard rails from season to season and the decline in the big reservoirs. And that’s really what they’re designed to do is to kind of absorb all of these kind of shocks to the system at the shorter time scales. They’ve been trending down for many, many years.

And so we had a couple of good winters and that’s the way that we would actually try to reverse that trend up with, with the rivers, but it’s just not been enough.

And, you know, we’re fighting against climate change as well where climate change, these warming temperatures just make the runoff efficiency, the ability of that snow to turn into stream flow gets into those reservoirs. We just lose that efficiency over time.

\

BRODIE: So I’m curious what you make of. So, you know, all of this, as we’ve been discussing sort of dichotomous data coming, obviously, you know, there’s some logistical reasons for it and some sort of timing reasons for it.

But if you just read the report, it seems like there’s quite a bit of juxtaposition of really good news and like not great news, all sort of rolled into one along with, as you referenced some surprises thrown in there about what, you know, what we got relative to what we expected. So I’m curious what you make of all that.

CRIMMINS: Yeah, that’s pretty normal for the Arizona climate is, is all of these juxtapositions all the time. And, and it’s the interesting thing about even studying drought here down in Arizona is that drought really is, there’s no one definition for it. And so we have to think about it in terms of time scale.

So if you’re worried about the reservoirs and you’re thinking about stream flow in the Colorado River, it’s big long time scales. If you’re worried about fire, if you’re worried about grazing, you’re gonna be thinking about much, much shorter timescales on seasons.

So it’s, it’s not uncommon for us to end up having a good season or maybe two seasons of precipitation. And things actually really turn around and look quite good on the landscape. Maybe fire risk goes down.

We end up having forage for livestock, but at the same time, we can still end up having that drought signal in the reservoirs. So you can end up having a conversation about drought and it can be a good conversation and a bad conversation at the same time depending on what you’re focusing on.

BRODIE: So, is any of this in any way predictive of what we can expect going into the fall and winter and spring of 2025?

CRIMMINS: Yeah. So one of the things that we rely on here in the southwest is we pay real close attention to the seasonal outlooks issued by the climate prediction center, which are really finely tuned to the El Nino southern oscillation. And so right now, we’re looking at La Nina forming, this one’s been really quite interesting. It’s been very fickle, quite slow to form.

The models aren’t super sure how strong it’s gonna peak at, but there’s still a decent chance we’ll have a weak La Nina event that will come online kind of midwinter. And typically, what that does, for us is it, it moves the jet stream pattern, to the north.

And so that will take some of those storms out of play that we would really rely on to give us an above average or average winter and probably lean us into the below average precipitation category for, for winter precipitation. So right now again, this is imperfect science from the forecasting perspective. Right now, we’re leaning towards a below average precipitation forecast for the upcoming winter and probably above average temperatures because when it’s dry here, it’s typically warm.

BRODIE: Right. Well, so then does that make, assuming that comes to pass, would that make the monsoon season next summer more important in terms of trying to sort of keep pace with getting some amount of precipitation?

CRIMMINS: Yeah, that’s exactly right. We really, and that’s, I think really interesting feature about Arizona that I think we live, we live down here and we, we know this, but I don’t think we appreciate the fact that we have two wet seasons.

We have the winter, which is very unique. You know, it’s upper elevation snowfall. It’s typically these long duration, low intensity precipitation gives us soil moisture that leads into the spring time. And then the monsoon is the other season that we were really rely on this precipitation is that it’s really hard for us to string together two average seasons, let alone three.

And so, yeah, we ended up having not a great monsoon, I think, by all accounts, if this winter is dry, we’re really gonna start sliding back into those short term drought conditions. You’re gonna start seeing the US drought monitor, which we’re already seeing start to fill back in across Arizona. And then we will really look to the monsoon season to hopefully start on time.

And so, yeah, we’re already thinking, you know, eight months out what next monsoon might look like.

3. Climate Change Is Drying Out The US West, Even When Rain Pours: Study.

BY SHARON UDASIN – 11/07/24 11:52 AM ET

Climate change-induced warming is drying out the American West by not only reducing precipitation, but also by accelerating evaporation — even amid adequate rainfall, a new study has found.

Evaporation accounted for 61 percent of the region’s drought severity from 2020 to 2022, while reduced precipitation was responsible for just 39 percent of these conditions, according to the study, published Wednesday in Science Advances.

Historically, drought in the U.S. West was driven by a lack of rainfall, while evaporative demand — the amount of water that the atmosphere can absorb from the Earth’s surface — has only played a small role, the study authors noted.

But climate change caused by burning fossil fuels has brought about higher average atmospheric temperatures and has increased the contributions of evaporation to drought severity, the researchers explained.

“For generations, drought has been associated with drier-than-normal weather,” co-author Veva Deheza, executive director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Integrated Drought Information System, said in a statement.

“This study further confirms we’ve entered a new paradigm where rising temperatures are leading to intense droughts, with precipitation as a secondary factor,” Deheza added.

To explore the impacts of higher temperatures on drought, the researchers separated “natural,” weather-driven droughts from those they attributed to climate change across a 70-year period.

They found that climate change was responsible for 80 percent of the surge in evaporative demand since 2000 and that during drought periods, this figure rose to more than 90 percent.

Climate change, they concluded, has been “the single biggest driver increasing drought severity and expansion of drought area since 2000.”

Comparing the 2000-2022 period to the 1948-1999 period, the scientists saw a 17 percent rise in average drought area due to an increase in evaporative demand.

Since the turn of the century, about 66 percent of the historical and emerging drought-prone areas had high evaporative demand that could alone cause drought — regardless of precipitation status, according to the study.

Prior to the year 2000, the same could only be said for 26 percent of that region, the researchers noted.

“During the drought of 2020–2022, moisture demand really spiked,” corresponding author Rong Fu, a professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences at the University of California Los Angeles, said in a statement.

A warmer atmosphere ends up holding more water vapor before the air mass becomes saturated and enables precipitation, the scientists explained. Heat keeps the water molecules moving and bouncing off each other, rather than condensing — a requirement for rainfall.

The result is a cycle in which the warmer the planet becomes, the more water will evaporate, but a smaller fraction will return as rain, according to the authors.

Fu explained that although the 2020-2022 drought period started with a natural decline in rainfall, its severity rose “from the equivalent of ‘moderate’ to ‘exceptional’ on the drought severity scale due to climate change.”

“Moderate” equates to about the 10 percent to 20 percent strongest droughts, while “exceptional” refers to the top 2 percent most severe droughts, per the U.S. Drought Monitor.

The scientists warned that severe droughts will likely go from exceedingly rare occurrences to happening every 60 years by the mid-21st century and every six years by the end of the century.

“Even if precipitation looks normal, we can still have drought because moisture demand has increased so much and there simply isn’t enough water to keep up with that increased demand,” Fu said.

“The only way to prevent this is to stop temperatures from increasing, which means we have to stop emitting greenhouse gases,” Fu added (editor emphasis).

Copyright 2024: EnviroInsight.org