Daniel Salzler No. 1061

EnviroInsight.org 3 Items July 31, 2020

Feel Free To Pass This Along To Others

If your watershed is doing something you would like others to know about, or you know of something others can benefit from, let me know and I will place it in this Information newsletter.

If you want to be removed from the distribution list, please let me know. Please note that all meetings listed are open.

Enhance your viewing by downloading the pdf file to view photos, etc. The

attached is all about improving life in the watershed.

This is already posted at the NEW EnviroInsight.org

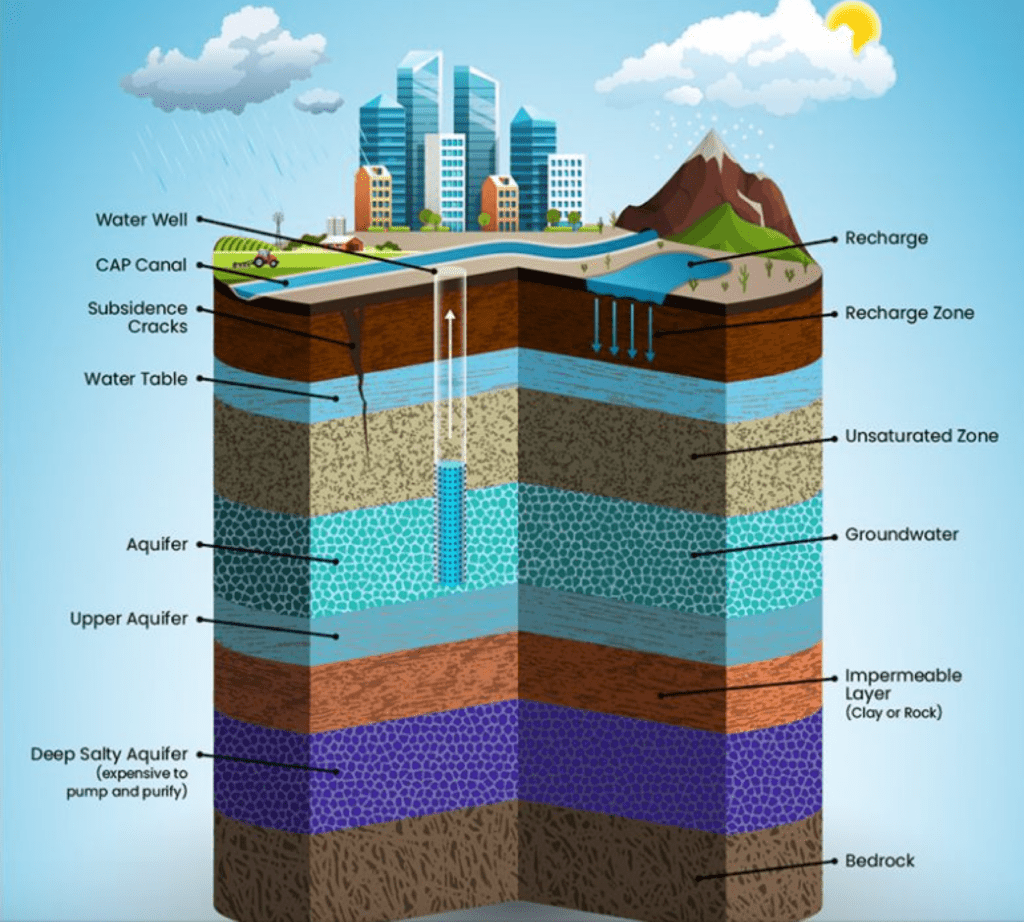

1. Aquifers: Sustaining Life In The Desert. This precious groundwater is used for many life-sustaining reasons. Riparian plants and trees absorb it through their roots to grow and thrive and people pump it up through wells for drinking, business and agriculture.

Beneath the dry desert earth are aquifers, layers of sand and gravel that store groundwater and willingly soak up any extra moisture sent its way.

This precious groundwater is used for many life-sustaining reasons. Riparian plants and trees absorb it through their roots to grow and thrive and people pump it up through wells for drinking, business and agriculture.

Unlike surface water, which is found above ground in lakes and rivers and replenished annually through rainfall and snowmelt, it can take many years for nature to fill an aquifer and little time for people to deplete it.

When this depletion happens, the water table drops and subsidence occurs; subsidence is when the layers of the aquifer compress causing the ground above to settle and crack, sometimes damaging roads, buildings and vital infrastructure.

CAP does two primary things to support aquifers and help prevent subsidence: delivers a renewable surface water supply and replenishes aquifers through a process called recharge.

Groundwater pumping is reduced through the delivery of renewable surface water from the Colorado River to central and southern Arizona. It is used by cities, tribal communities and agriculture.

Aquifers are replenished through recharge, a process that allows water to flood an area of land and percolate down through the soil where it is stored in the aquifer. CAP has developed seven recharge projects to store Colorado River water and currently owns six and operates five.These two approaches are critical to maintaining the health of Arizona’s aquifers and ensuring a reliable water supply for many years to come.

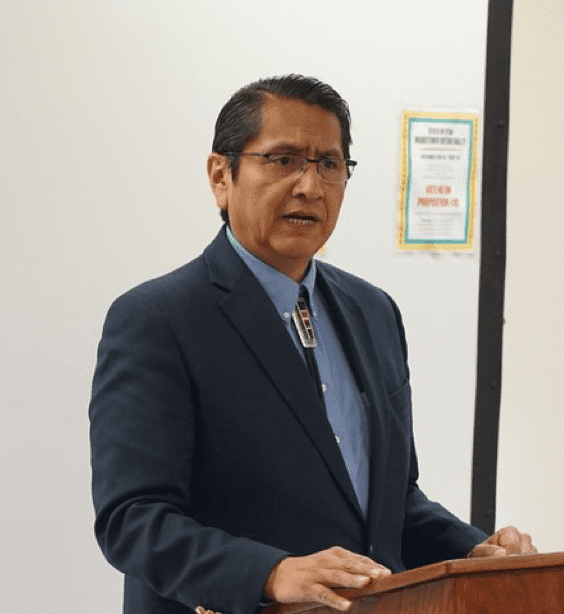

2. Navajo Nation Residents Hope Federal Act, Aid Will Finally Bring Big Water Projects. Last summer, Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez sat before the U.S. House Natural Resources Committee and pleaded for the passage of a bill that would formalize water rights for the Utah portion of the Navajo Nation.

“More than 40% of Navajo households in Utah lack running water or adequate sanitation in their homes,”Nez said in the June 2019 testimony. “In some cases, such as in the community of Oljato on the Arizona-Utah border,a single spigot on a desolate road, miles from any residence, serves 900 people. The legislation provides the means to address these critical needs of the Navajo people.”

Nine months later, the critical needs Nez described became even more urgent, after a man unknowingly carried the coronavirus from a baseball tournament in Tucson, Ariz., to the Navajo Nation community of Chinchilbeto, Ariz., not far from the Utah line.

Thevirus spread at a church rally March 7 — the pastor giving the sermon reportedly had a cough — and ripped through the northern Navajo Nation over the next few months, prompting lockdowns, curfews and mask orders.

An elderly woman and her son from Navajo Mountain, Utah, died within days of each other in late March after running out of water in their off-grid home while quarantining with the virus. As of Sunday, July 26th COVID-19 had taken 434 lives on the Navajo Nation, which has an on-reservation population of about 174,000. That translates to a higher per capita rate than any U.S. state, and Nez has repeatedly drawn connections between the severity of the outbreak and the lack of running water in so many households.

It was in this context that the Navajo Utah Water Rights Settlement Act, which Nez testified on behalf of last year, was revived. The settlement formalizes an agreement among Utah, the federal government and the Navajo Nation that was worked out over more than a decade of negotiations. Talks over the deal began in 2003, and the bill was first introduced in Congress by then-Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, in 2016 Hatch’s successor, Utah Republican Sen Mitt Romney, reintroduced the legislation last year, but it didn’t pass until June, after the pandemic had turned water availability on the reservation into a national issue.

The House version of the bill, co-sponsored by Utah’s entire congressional delegation — three Republicans and one Democrat — has yet to see a vote.

If it passes into law, the legislation would recognize the Navajo Nation’s right to 81,500 acre-feet of water from the Colorado River Basin each year, and it would provide $210 million in funding for water improvements on Navajo Nation lands in southeastern Utah. An additional $8 million has been approved by the state of Utah.

Expanding water access has broad support among the American public during the coronavirus pandemic. A June poll from Climate Nexus, in partnership with Yale and George Mason universities, found 84% support for allocating federal dollars to provide clean water to the 2 million Americans currently without running water, many of whom live on Native American reservations.

Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez speaks to the media in Window Rock, Ariz., the Navajo Nation capital, Oct. 29, 2019.”

According to Nez, the Utah settlement would save the federal government millions of dollars in litigation costs and help the United States meet its treaty obligations.

“The passage of this legislation will also advance the commitments made in the Treaty of 1868, where Navajo leaders pledged their honor to keep peace with the United States and, in return, the United States pledged to the Navajo people … their permanent homeland,” Nez said. “In the arid West, it is clear — no lands can be a permanent homeland without an adequate supply of water, especially potable water.”

Even before the pandemic, the public health benefits of water funding were clear. According to an analysis by the Indian Health Service, every dollar the agency spends on home sanitation facilities achieves at least a twentyfold return in health benefits.

“We’re under a very serious pandemic emergency,” said James Adakai, president of the Oljato Chapter and manager for the Navajo Nation Capital Projects Management Department, which works on water and electrical improvements. “We need to get clean water to the homes. To improve the living conditions of Navajo families, we need long-term, reliable water sources, which the Utah Navajo Water Rights Settlement Act will provide.”

Adakai said the $218 million in funding from the state and federal governments would be significant seed money but might not be enough to connect all Utah Navajo households to water. In some cases, he said, it could cost between $150,000 and $250,000 to connect a single household.

The disbursement of the bulk of the funds was delayed by the federal government by nearly two months, and more recently a debate within the Navajo Nation government over how to spend the money has led to additional delays with presidential vetoes and stalemates within the Navajo Nation Council.

The CARES Act money must be spent by Dec. 31 under current rules, and Arlyssa Becenti, government reporter for The Navajo Times, said some constituents worry about time running out.

“They’re not liking the fact that legislative and executive [branches] are fighting over the money and where it should go,” Becenti said, adding thatsmall protests have recently broken out over the issue in the Navajo Nation capital of Window Rock, Ariz. Some critics have suggested giving out the money directly to individual tribal members.

But the prolonged debate can obscure a base of widespread agreement over spending priorities. “Water, electricity and broadband — those are the main components,” Becenti said. “Those three are what the council wants, the president wants, and the protesters want.”

As political efforts to expand water access grind forward and as nonprofits work on interim solutions, a low-pressure public spigot in the Oljato Chapter near Monument Valley that Nez referred to in his congressional testimony is as crowded as ever with pickup trucks lined up every day, waiting to fill portable tanks and haul the water home. Source: Salt Lake Tribune

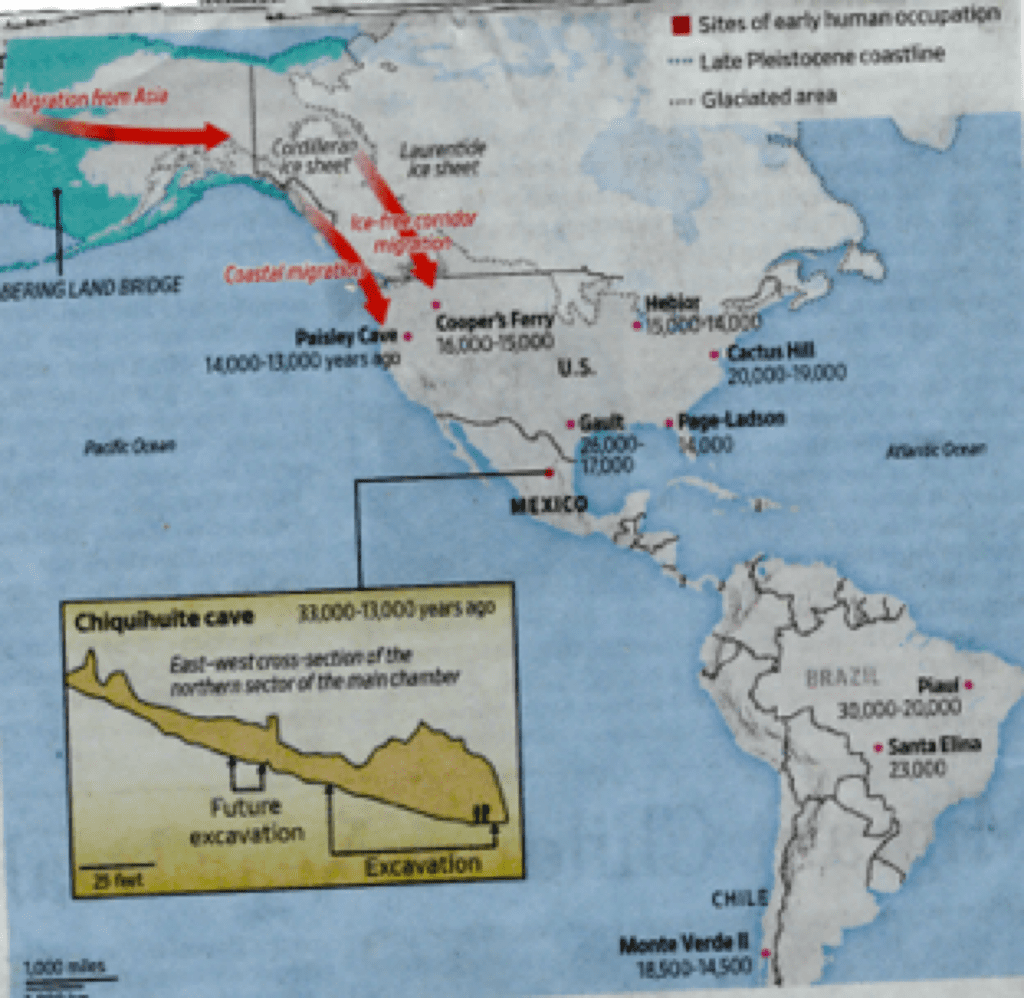

3. Humans In America 30,000 Years Ago, Far Earlier Than Thought. Paris (AFP) – Tools excavated from a cave in central Mexico are strong evidence that humans were living in North America at least 30,000 years ago, some 15,000 years earlier than previously thought, scientists said Wednesday.

Artefacts, including 1,900 stone tools, showed human occupation of the high-altitude Chiquihuite Cave over a roughly 20,000 year period, they reported in two studies, published in Nature.

“Our results provide new evidence for the antiquity of humans in the Americas,” Ciprian Ardelean, an archeologist at the Universidad Autonoma de Zacatecas and lead author of one of the studies, told AFP.

“There are only a few artefacts and a couple of dates from that range,” he said, referring radiocarbon dating results putting the oldest samples at 33,000 to 31,000 years ago.

“However, the presence is there.” No traces of human bones or DNA were found at the site.

“It is likely that humans used this site on a relatively constant basis, perhaps in recurrent seasonal episodes part of larger migratory cycles,” the study concluded.

The stone tools — unique in the Americas — revealed a “mature technology” which the authors speculate was brought in from elsewhere.

The saga of how and when Homo sapiens arrived in the Americas — the last major land mass to be populated by our species — is fiercly debated among experts, and the new findings will likely be contested.

‘Clovis-first’ debunked

Until recently, the widely accepted storyline was that the first humans to set foot in the Americas crossed a land bridge from present-day Russia to Alaska some 13,500 years ago and moved south through a corridor between two massive ice sheets.

Archeological evidence — including uniquely crafted spear points used to slay mammoths and other prehistoric megafauna — suggested this founding population, known as Clovis Culture, spread across North America, giving rise to distinct native American populations.

But the so-called Clovis-first model has fallen apart over the last two decades with the discovery of several ancient human settlements dating back two or three thousand years before earlier. Moreover, the tool and weapon remnants at these sites were not the same, showing distinct origins

“Clearly, people were in the Americas long before the development of Clovis technology in North America,” said Gruhn, an anthropology professor emerita at the University of Alberta, in commenting on the new findings.

In a second study, Lorena Becerra-Valdivia and Thomas Higham, researchers at the University of Oxford’s Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit, used radiocarbon — backed up by another technique based on luminescence — to date samples from 42 sites across North America.

Using a statistical model, they showed widespread human presence “before, during and immediately after the Last Glacial Maximum” (LGM), which lasted from 27,000 to 19,000 years ago.

The timing of this deep chill is crucial because it is widely agreed that humans migrating from Asia could not have penetrated the massive ice sheets that covered much of the continent during this period.

“So if humans were here DURING the Last Glacial Maximum, that’s because they had already arrived BEFORE it,” Ardelean noted in an email. Human populations scattered across the continent during an earlier period also coincide with the disappearance of once abundant megafauna, including mammoths and extinct species of camels and horses.

“Our analysis suggests that the widespread expansion of humans through North America was a key factor in the extinction of large terrestrial mammals,” the second study concluded.

Many key questions remain unanswered, including whether the first of our species to wander across the frozen tundra of Beringia made their way south via an interior route or — as recent research suggests — by moving along the coast, either on foot or in boats of some kind.

It is also a mystery as to “why no archaeological site of equivalent age to Chiquihuite Cave has been recognized in the continental United States,” said Gruhn.

“With a Bering Straits entry point, the earliest people expanding south must have passed through that area.”

Copyright EnviroInsight.org