Daniel Salzler No. 1051

EnviroInsight.org 6 Items May 29, 2020

—————Feel Free To Pass This Along To Others——————

If your watershed is doing something you would like others to know about, or you know of something others can benefit from, let me know and I will place it in this Information newsletter.

If you want to be removed from the distribution list, please let me know. Please note that all meetings listed are open.

Enhance your viewing by downloading the pdf file to view photos, etc. Theattached is all about improving life in the watershed.

This is already posted at the NEW EnviroInsight.org

1. While At Home, Protect Your Pets From Toxic Plants Found Inside And Outside The House. 5.5% of all poisioning were when pets chewed on plants that are toxic include:

Toxic to Cats:

Amaryllis Castor Bean

Chrysanthemum Cyclamen

English Ivy Kalanchoev

Lilies Oleander

Sago Palm

Toxic to Dogs:

Elephant Ear (Caladium) Aloe

Amaryllis American Holly

Apple seeds (including crabapples) Calla Lilly

Apricot Bay Laurel

Boxwood Burning Bush (Wahoo, Spindle tree)

Carnation Castor Bean Plant

Chamomile Cherry pits (Prunes spp.)

Chives Chrysanthemum

Daffodil Nightshade (Tomatoes, potatoes, peppers)

Source ASPCA

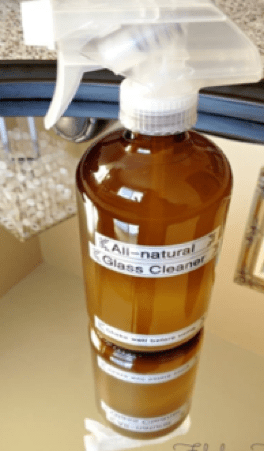

2. Make Your Own Natural Glass Shower Door Cleaner.

Remove those hard water (calcium) stains from your glass

shower doors. Mix 1 teaspoon of Borax, 1 tablespoon of Castile

soap, 2 tablespoons of white vinegar, 2 cups of water and if so

desired, 5 drops of an essential oil. Spray on doors and wipe

clean. Rinse. Source: Family Handyman, May 2020

3. 16 Best Sunscreens For Your Kids. The best sunscreens for your kids are:

Adorable Baby Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30+

All Good Kid’s Sunscreen Butter Stick, SPF 50+

Badger Baby Active Sunscreen Cream, Chamomile & Calendula, SPF 30

Erbaviva Organic Skincare Baby Sun Stick, Lavender Chamomile, SPF 30

Just Skin Food Baby Beach Bum Sunscreen Stick, SPF 31

Olita Kids Mineral Sunscreen Sunstick, SPF30

Raw Elements Baby + Kids Sunscreen Lotion Tin, SPF 30

Star Naturals Baby Natural Sunscreen Stick, SPF 25

SunBioLogic Kids Sunscreen Stick, SPF 30+

Suntribe Kids Mineral Sunscreen Lotion, Vanilla Yum Yum, SPF 30

thinkbaby Body & Face Sunscreen Stick, SPF 30

thinksport Kids Body & Face Sunscreen Stick, SPF 30

TruBaby Water & Play Mineral Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30+

TruKid Sunny Days Sport Mineral Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30

UV Natural Baby Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30+

Waxhead Sun Defense Baby Zinc Oxide Vitamin E + D Enriched Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 35

Source: EWG 2020

4. Complex Dynamics Of Water Shortages Highlighted In Study. By S.Kacapyr | May 18, 2020. Within the Colorado River basin, management laws dictate how water is allocated to farms, businesses and homes. Those laws, along with changing climate patterns and demand for water, form a complex dynamic that has made it difficult to predict who will be hardest hit by drought.

Cornell engineers have used advanced modeling to simulate more than 1 million potential futures – a technique known as scenario discovery – to assess how stakeholders who rely on the Colorado River might be uniquely affected by changes in climate and demand as a result of management practices and other factors.

Their results are detailed in “Defining Robustness, Vulnerabilities, and Consequential Scenarios for Diverse Stakeholder Interests in Institutionally Complex River Basins,” published May 12 in the journal Earth’s Future. The report specifically examines a section of the Colorado River’s upper basin, where agricultural, municipal, recreational and industrial activities with rights to the water are worth an estimated $300 billion a year.

In Colorado, resource planning for the state’s major water basins is informed by a collection of databases, management tools and models developed by the Colorado Water Conservation Board and the Division of Water Resources. These tools have been used to conduct detailed studies of how specific water users may be impacted by climate change, but the studies considered only a few climate scenarios.

“Computing and other technical constraints limited their ability to explore combinations of human and climate pressures for the hundreds of stakeholders in the system,” said Antonia Hadjimichael, a postdoctoral researcher in the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering and senior author of the paper. Patrick Reed, the Joseph C. Ford Professor of Engineering, is a co-author.

Public agencies want to know which potential changes cause individual water shortages so they can adapt their water management policies to address them. For instance, a boom in population suggests water conservation programs may be the best strategy, or limiting the growing season for a particular crop may offset water shortages due to irrigation.

“We were able to work together to consider a diverse set of potential futures in our exploratory modeling that helped us discover in finer-grained detail how individual water users’ vulnerabilities may differ substantially,” said Reed.

In order to account for the myriad laws, climate patterns and water demands, among other factors, Hadjimichael and co-authors used the Colorado Water Conservation Board’s model to simulate more than 1 million potential scenarios, depicting the Colorado River basin and its dependents in a collection of possible futures. The simulation offers a diverse view of each dependent’s vulnerability to a water shortage.

One key finding: Different local stakeholders experience the same drought in potentially very different ways, even when they are located near each other or possess similar rights to the water. This poses a challenge because studies that look at average vulnerabilities across groups – such as farmers, residents or businesses – or regions would miss critical details.

“For example, farmers located in the same county using water from the same river source might have very different water shortages during a drought,” Hadjimichael said, noting the model suggests historical data can’t always be relied upon to infer future impacts.

“These differences are due to complex relationships between their water rights, locations and the simulated future changes in climate and demands that we are still working to better understand,” Hadjimichael said.

Preparing for an uncertain future is especially important for the Colorado Water Conservation Board and other western U.S. policymakers as they continue to face unprecedented drought conditions. In the past two decades, the Colorado River basin has experienced its lowest period of inflow in more than 100 years of record keeping, and reservoir storage has declined from nearly full to about half of capacity, according to the U.S. Department of the Interior.

The paper’s authors suggest that the laws dictating rights to water resources are fundamental components shaping how stakeholders experience drought, and that predicting individual impacts requires models based on more than just simplified metrics and generic regional assessments.

Contributing to the project were researchers from the University of Virginia, Wilson Water Group, Black and Veatch, the National Center for Atmospheric Research, and the Colorado Water Conservation Board.

The research was partially funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.S. Kacapyr is public relations and content manager for the College of Engineering

5. WEF And An AZ Congressman Supporting Water Workforce Needs. The Water Environment Federation (WEF) is a nonprofit association that provides technical education and training for thousands of water quality professionals who clean water and return it safely to the environment. WEF members have proudly protected public health, served their local communities and supported clean water worldwide since 1928.

WEF has been working with AZ Congressman Greg Stanton on a provision in a bill that supports water workforce needs. It gives states the authority to set aside one percent of their federal capitalization grant to go toward workforce development programs. Source: WaterWorld magazine. March 2020.

6. Bet You Didn’t Know. Cement is the glue that holds sand and gravel together, forming it into concrete. Making it, though, requires temperatures of at least 1400°C (2552°F)—and the chemical reaction that creates cement releases CO2 as well. If the cement industry were a country, it would be the third-largest producer of greenhouse gases on Earth.

In order to meet the targets set at the Paris Agreement, nations around the world must reduce cement emissions by a quarter in the next 30 years, literally reimagining the walls around us.

Here’s how cement is cleaning up its act in the present—and how it gets even better in the future.

Splitting water

Last year, researchers at MIT successfully demonstrated in the lab that it’s possible to use electrolysis instead of heat to make cement. The process splits water molecules to make an acid, which then dissolves limestone and triggers the chemical reaction. Unfortunately, this still produces CO2. But unlike the dirty gas released when cooking up cement, this CO2 is pure enough to be sequestered, or used for other purposes, such as in soft drinks or as liquid fuel.

What remains to be seen is how well the process can be scaled up to work in an actual cement plant.

Don’t let coal ash go to waste (but it’s better to have no coal ash in the first place)

While traditional cement production heats limestone and clay in a kiln, triggering a chemical reaction that releases CO2, geopolymer cement uses industrial waste products like coal ash to accelerate the chemical reaction, which requires less heat. While it may eliminate CO2 emissions by up to 80 percent, a downside is its reliance on polluting industries. With coal plants going bankrupt, coal ash is not as available as it once was—nor should it be.

Friendly bacteria

North Carolina engineering firm bioMASON raises vats of bacteria and mixes it with sand, regularly watering it until it hardens into a solid surface made of calcium carbonate structures similar to coral. The US Air Force, which is highly interested in any technology that does not involve transporting a cement mixer into a war zone, is testing biocement for military runways, but it is not yet on the market.

Recycle the old stuff

Recycling concrete keeps this nonbiodegradable material from occupying landfill space, and the technology is simple: Crush it and mix the results with fresh cement or use it to create new products like pavement and gravel. Energy is required to power a crushing machine, but when crushed, previously unexposed parts of the concrete are exposed and absorb additional CO2 from the atmosphere, through the process of carbonation. Unfortunately, recycled concrete is not universally trusted, as its strength and durability can vary.

Carbon sequestration

Carbon injection places CO2 into wet concrete inside the cement mixer, where it chemically reacts and transforms into a mineral, never to be released as a gas. The technology is already in use in places like Atlanta, Georgia, and Honolulu, Hawaii. The downside: Since the CO2 is added to concrete, not cement, it’s not reducing the emissions from cement production itself. The sequestered gases are captured from other industrial sources, like fertilizer manufacturing. Source: Sierra Club, May 23, 2020

Copyright EnviroInsight.org 2020