1. It’s Still April, And April Is Water Awareness Month. Start now and continue on throughout the year. For the past 10 years, the Arizona Department of Water Resources and more than 200 water conservation partners around the state have been celebrating April as Water Awareness Month (WAM). Check around your home//office for leaks and review your daily/weekly water usage.

Visit arizonawaterfacts.com/wam for water related information to help homeowners become water efficient in easy and creative ways. The web site also provides information on low-water use plants, how to find and fix water leaks, rainwater harvesting, and more.

2. Arizona’s Citizen Scientists Make an Impact. by Sam Potteiger, WRRC Student Outreach Assistant. Natural resource scientists and managers depend on data, which is often costly and difficult to collect. Citizen science engages members of the community in scientific investigations through observation and other data collection activities. Opportunities for citizen involvement are increasing as the value of “crowd sourcing” is recognized and strategies are developed for assuring data quality. In Arizona, citizen science has been employed to provide data on rainfall, streamflow, and water quality, among other topics.

Rainlog, a cooperative rainfall monitoring network for Arizona, was developed at the University of Arizona. Because rain gauges in Arizona are sparse, there are large gaps in rainfall data coverage. This data sparseness translates to difficulty in accurately estimating precipitation. Citizens who participate in Rainlog are helping to fill data gaps by measuring and reporting rainfall at their homes or work places. To encourage wide- spread participation, Rainlog was developed to be easily accessible. Anyone with a rain gauge and access to the Internet can participate. Data collected through the Rainlog network is used for a variety of applications, including watershed management, weather reporting, hydrologic research, and drought planning. Participants can see their observations and the observations of neighbors instantaneously. Rainlog displays all data on real-time, high-resolution precipitation maps on its web page. These maps are useful in tracking variability in precipitation patterns and potential changes in drought status.

A well-established application of citizen science in Arizona is wet/dry mapping. The Nature Conservancy launched this program on the San Pedro River in 1999 to monitor the extent of flow in the river in the driest part of the year. On the third Saturday in June, volunteers walk, ride on horseback, or even kayak along discrete stretches of more than 220 stream miles. They are trained to use GPS units to pinpoint where the flow starts and ends. With this data, The Nature Conservancy hopes to assist scientists and water managers to quantify long-term trends in surface water patterns, better understand groundwater/surface water interactions, and manage wildlife populations and riparian habitats. Already, mapping has helped preserve the welfare of the San Pedro. Data from the first 12 years of wet/dry mapping show a steady increase in the wetted section of a five-mile stretch of the river where irrigated farms were retired for water conservation. Because of the success of wet/dry mapping of the San Pedro, similar efforts have been undertaken elsewhere in Arizona, including the Agua Fria River, Cienega Creek, and at tributaries to the San Pedro. Mapping at Cienega Creek even revealed a previously unmapped perennial stretch of the stream.

Riverwatch, an effort by the Friends of the Santa Cruz River (FOSCR), is another wellregarded example of citizen science in Arizona. Riverwatch is FOSCR’s water quality monitoring volunteer group. Each month, the group samples the river for physical, chemical, and biological water quality parameters. Field monitoring data has been collected by FOSCR along the Santa Cruz since 1986. Because of the extent and quality of its database, FOSCR frequently collaborates with the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ), other government agencies, and various research groups. One dataset provided by FOSCR was instrumental in securing $59 million in federal funding to upgrade a treatment plant, greatly improving water quality in the flow downstream from the plant—which Riverwatch has documented.

ADEQ has recognized the value of citizen science and has made it the focus of its new initiative, Arizona Water Watch. The initiative has two programs designed for volunteers aged ten and up: Citizen Science Water Monitoring and the Arizona Water Watch mobile app. Citizen Science Water Monitors undergo training to collect and prepare water samples for testing to help scientists find pollution sources and monitor restoration projects. By working with ADEQ scientists, citizens are able to design studies for their waterways and play an important role in their environmental protection. The Arizona Water Watch mobile app is simple and easy to use and anyone with a smartphone can download it for free from the app store. The citizen scientist visits a water body and takes a picture of it. Location coordinates are automatically recorded from the phone’s GPS. Next, participants answer a series of “yes/no” questions about the body of water. Finally, Page 2 users submit their observations, which are automatically entered into an ADEQ database. Scientists then use the data in analyzing water quality issues, updating flow data, and identifying water bodies for future studies.

Citizen science is also a powerful tool for scientist-community collaboration. Dr. Monica Ramirez-Andreotta integrates this approach into her National Science Foundation (NSF) funded project, Gardenroots, which trains people in underserved communities to monitor the quality of their harvested rainwater, garden soil, and home garden crops. Participants take samples of their garden soil, the water from the garden hose, a few vegetables from the garden, and a few clippings from garden plants. Some samples they analyze themselves and others they hand over to a laboratory for analysis. A key tenet of the project is to utilize citizen science as a means of empowering communities. Dr. RamírezAndreotta is quoted on the Gardenroots website commending the ability of citizen science as a process that “not only makes scientific information more readily available, it also engages community members in the process of scientific inquiry, synthesis, data interpretation, and the translation of results into action.” Through participation in Gardenroots, underrepresented populations can have an improved understanding of environmental health, allowing them to more readily participate in environmental decision-making.

Citizen science is an important resource for scientists. In Arizona, citizen science efforts have demonstrated the value of citizen participation in data collection and connecting the scientific community with the public. The ADEQ’s new Arizona Water Watch mobile app points the way toward broad public engagement in generating scientific knowledge.

3. Western Arizona Eyed As Water Source For Major Metro Areas FLAGSTAFF, ARIZ

A week into her appointment last fall as a Mohave County supervisor in western Arizona, Lois Wakimoto heard the words that would consume her since: We have a water problem.

The entity that sends Colorado River water throughout Arizona wants to buy farmland in her district that includes Mohave Valley, pay farmers to fallow it and redirect the water to the state’s most populous areas where housing developments are booming.

The program would be the first in the state to move water from agricultural users along the river to central and southern Arizona, and local residents are opposing it.

“As they want to take what they say is excess because we’re not using it and store it for their future growth, we look at that and say, ‘what about our future growth?'” Wakimoto said.

The Central Arizona Groundwater Replenishment District doesn’t need Mohave County’s approval to proceed but plans could be delayed if the county government sues as planned.

The replenishment district, part of the Central Arizona Project, delivers 30,000 acre-feet of water annually to aquifers in Pinal, Pima and Maricopa counties, but expects that figure to at least triple as new housing is built. An acre-foot (1,233 cubic meters) is enough to supply a typical family for a year.

The district is state mandated to look for new water sources. Its portfolio includes water leases from an Arizona tribe and a private utility, storage credits, river water, and, potentially, the small town of Quartzsite.

Without more water, “there would be a fairly significant impact to the economy of the state of Arizona,” said district manager Dennis Rule.

The 2,200 acres (890 hectares) of farmland in western Arizona’s Mohave Valley Irrigation and Drainage District could add 5,500 acre-feet (6.8 million cubic meters). The $34 million deal is far from final, needing approval from the Mohave Valley Irrigation and Drainage District board, the state water agency and the Interior Department.

But talk of it has raised tension among residents and the board that oversees the seven farms and the 14,000 acre-feet (17.3 million cubic meters) of water tied to them that includes coveted senior water rights.

Public attendance at the district’s monthly meetings generally is scant but ow dozens show up, even when the sale isn’t on the agenda. Minutes into the February meeting, one man asked what was on everyone’s mind: “Why does Phoenix want our water?” Wakimoto, who comes from a farming family, took a front-row seat. She’s urged residents to write letters, held town halls and questioned the board’s motives.

“We are a community that has really all of a sudden realized that our entire future and the legacy we leave our children is at stake,” she said.

Long-term fallowing programs around the Colorado River basin have benefited big cities like Los Angeles and San Diego.

The Central Arizona Groundwater Replenishment District paid farmers in Yuma $750 an acre to forego planting on parts of 1,500 acres (607 hectares) over three years, saving 21,500 acre-feet (26.5 million cubic meters) of water used to prop up Lake Mead. The district proposed extending the $3.2 million program but Yuma Mesa Irrigation District manager Pat Morgan said farmers declined

In Mohave Valley, the replenishment district has proposed fallowing up to half of the 2,200 acres (890 hectares). Farmers there mostly grow cotton, wheat and alfalfa.

The deal won’t work unless the Mohave Valley Irrigation and Drainage District allows water to leave its boundaries.

Under a draft resolution, the water couldn’t leave forever. Board Chairman Chip Sherill said the district also wants assurances it doesn’t lose out if a shortage is declared on the Colorado River.

Farmers use most of the district’s Colorado River supply, with some reserved for growth, Sherill said. “We have a sufficient amount of water with Mohave Valley to take care of our water needs for many, many years to come.”

The Mohave County Board of Supervisors has set aside $20,000 to draft a lawsuit against the irrigation district if a water transfer passes and bought 15 acres (6 hectares) of farmland there to establish legal standing.

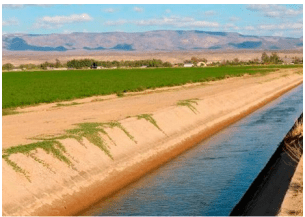

If the replenishment district’s proposal succeeds, water savings would be diverted upstream and sent through canals to aquifers around Phoenix and Tucson.

“This board will be transferring wealth from Mohave County to central Arizona,” said county lobbyist Patrick Cunningham. “We think that is flat-out bad policy. It’s wrong. This water should stay where it’s reserved.”

Perri Benemelis, the replenishment district’s water supply manager, said the prospect of a lawsuit is disappointing. She believes everyone can benefit under the right terms

“We’re trying to implement our program in a responsible way,” she said. “If we go after water supplies, and they have an adverse effect in the community, we’re not going to be able to do the next transaction.”

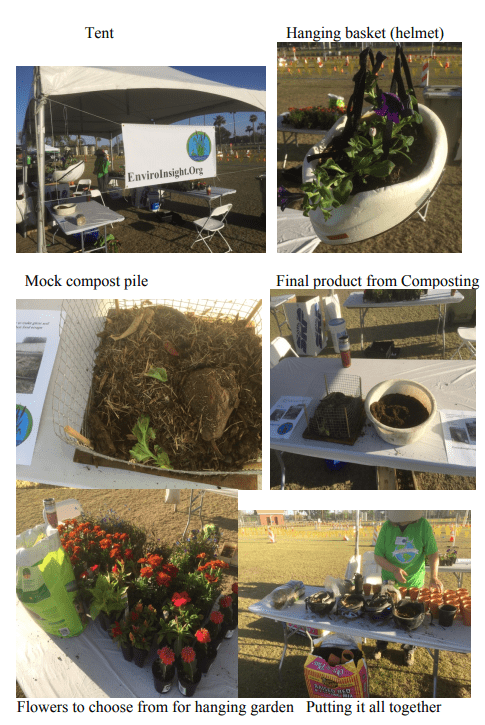

4. EnviroInsight Teaches Young And Old How To Make Hanging Gardens From Repurposed Bicycle Helmets. EnviroInsight, a not-for-profit- organization, demonstrated to those who turned in an old bicycle helmet to the City of Glendale, for a new one, how to make hanging gardens from their old helmets.

Over 200 people spent time with the members of EnviroInsight non-profit- organization constructing hanging gardens from old helmets placing two to three flowering plants into each helmet. Approximately 50 more citizens used small clay pots to plant a single plant to watch it grow. The event was sponsored by the City of Glendale and all of the soil, and plants were donated by Home Depot. All of the fun was created by those who participated.